Creative Identities in Creative Online Communities

by Tikvah Jesse Vismer

Abstract

The following paper argues that social media has not weakened creative identity in the creative communities online. This paper uses a number of journal articles, the book Steal Like an Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative by Austin Kleon, as well as the Instagram photographer Dominique Davis, @allthatisshe, as a case study. The following paper will introduce the idea of identities and communities and will look at the concept of a creative community and the concept of a creative identity within this community. Then, it will discuss the concept of originality and demonstrate how originality. Next, this paper will discuss the concept of remixing and how this concept is linked to the concept of originality. Finally, using one Instagram photographer as a case study, this paper will aim to specifically use the concepts of originality and remixing to prove that social media has not weakened a creative’s identity in the creative communities online.

(Note: The photo set as my featured image is my own work)

Conference Paper

Introduction

Identity, the idea of identity, and the consciousness of one’s identity has always existed. This identity can be defined as “the fact of being who or what a person or thing is” (Oxford Dictionary, 2018). As seen by Pirandello, an identity is something which is fabricated and the idea of one’s identity is dependent on the love and loyalty of others for its existence, and therefore, the performance and action through which identity is created is important (Merchant, 2006). The idea of community is something that has been constructed and is something which has also always existed. Community can be defined as “a group of people living in the same place or having particular characteristics in common” (Oxford Dictionary, 2018). Online communities developed around social media sites exist in much the same way as well as vary, just as they do offline so to speak. Social media has become the foundation for an extensive range of practices and interests. Even though social media sites have users from all around the world, people come together to form communities based upon shared activities, interest, etc (Boyd and Ellison, 2007).

In these online communities, identity plays a very important role. In these types of communities, people can be whoever they want to be and they can choose what they wish to reveal or even make up about their identity (Pearson, 2009). This freedom found on the Internet through social media allows people to experiment with their identity and has provided both new potentials and challenges for the idea of identity. These communities have both created an opportunity for people to re-invent themselves, help in portraying themselves in new ways, or be a platform for people to express themselves and their identity. (Merchant, 2006). The idea of a community and the idea of having an identity are both dependant on the other in the way that an individual has an identity because they belong to any certain community, and therefore, one may very well have more than one identity or choose what parts of this identity to reveal to which community. Among many of the communities online, the creative community is one that is quite extensive, consisting of many different fields of creativity. Within these creative communities are many different creative identities, and like in any community, there are issues relating to one’s creative identity.

The following paper will look at the concept of a creative community as well as the concept of a creative identity within this community and argue that social media has not weakened identity in the creative communities online. More specifically this paper will aim to look at a photographer’s identity on Instagram. Firstly, this paper will describe and define creative communities and creative identities in more depth. Then, it will discuss the concept of originality and demonstrate how originality is linked to identity as well as how the concept of originality supports the argument. Next, this paper will discuss the concept of remixing and how this concept is linked to the concept of originality, as well as demonstrate how the concept of remix supports the argument. Finally, using one Instagram photographer as a case study, this paper will aim to specifically use the concepts of originality and remixing to prove that social media has not weakened a creative’s identity in the creative communities online.

Creative communities and creative identities

Firstly, having described the basic concept of identity and community, it can now be explained what is meant by creative communities online as well as what identity refers to in the context of this paper. The word creative can be defined as “relating to or involving the use of the imagination or original ideas to create something; having good imagination or original ideas” (Oxford Dictionary, 2018). An alternate definition of the concept of community is “the condition of sharing or having certain attitudes and interests in common” (Oxford Dictionary, 2018). Therefore, by combining the definitions of ‘creative’ and ‘community’, one can identify the concept of a creative community. A creative community can then be said to be a place where people who are creative share common interests, that is, their creativity, their want to create, and the medium used to express this creativity. Creative communities extend over numerous social media platforms and branch off into many common interests, such as on Instagram with photo content, on YouTube with video content, as well as blogs and many others.

Looking at another definition, identity can also refer to “the characteristics determining who or what a person or thing is” (Oxford Dictionary, 2018). Jenkins (1996) once referred to identity as “the ways in which an individual and collectives are distinguished in their social relations with other individuals and collectives” (as cited in Fearon, 1999). In the context of this paper, another word to describe identity is ‘aesthetic’, which can be defined as “a set of principles underlying the work of a particular artist or artistic movement” (Oxford Dictionary, 2018). Therefore, when identity, or rather creative identity, is referred to in this paper, it specifically refers to the characteristics that distinguish one artist from another through their specific aesthetic or style. This type of identity in creative communities relates to creative performance and is connected to how much of it is valued by the creative (Glaveanu and Tanggard, 2014). Therefore, more specifically in the further context of this paper, the concept of creative identity will refer to the aesthetic or style an individual photographer has that is evident in his work, or photographs. This specific style or aesthetic then creates a certain creative identity for the photographer within the creative community on Instagram and it is by this identity that the photographer is known.

The concept of originality

Now that the concepts of creative communities and context of identity has been defined, the concept of originality can be discussed as well as how originality is linked to a creative’s identity and how this can prove that social media has not weakened a creative’s identity in the creative communities online. The core of the argument of whether or not social media has weakened a creative’s identity is the issue of originality and the sensitivity of people when it comes to being inspired by another creative’s identity. There is much argument, across many social media platforms, especially Instagram and YouTube, over whether or not being inspired by another creative’s identity and imitating their work is stealing from and weakening their identity as a creative.

The first problem with claiming that people are stealing from or copying other creative’s identities is that no identity is original, or completely their own, to begin with. Nothing is new and nothing is original. As the well-known writer, Anton Chekov (1860-1904) once quoted, “There is nothing new in art except talent” (as cited on Good Reads, 2018). Therefore, no one has a creative identity that is just theirs, the only thing that one has that is different is their talent. When asked about where creative ideas come from, an honest creative will say that they were stolen. Nothing is original and all creative work is built on what came before. It is important to understand that nothing comes from nowhere. On the notion that nothing is truly original, originality can be seen rather as uniqueness (Simonton, 2016). No creative person is born with their creative identity, style, or aesthetic. An individual learns who they are, and they learn this through copying. Copying, however, in this case refers to practice, not plagiarism, as that is when one tries to pass another’s work off as their own, and a true creative is not trying to do that. A creative is a selective collector of ideas they love, and they accept inspiration instead of run from it (Kleon, 2012). William Ralph Inge once stated, “What is originality? Undetected plagiarism” (as cited by Kleon, 2012, p.8). The idea of a creative identity is linked to the idea that their identity is original. However, this cannot be the case, as mentioned earlier, nothing can ever be completely original. Therefore, due to the fact that nothing is original to begin with, creative identities in online creative communities cannot be weakened, as each creative identity was initially inspired by someone else’s identity.

The concept of remixing

Next the concept of remixing will be discussed and how remixing can be connected to originality as well as how this concept can support the argument that social media has not weakened creative identity in the creative communities online. The word remix can be defined as to “produce a different version of (a musical recording by altering the balance of the separate tracks” (Oxford Dictionary, 2018). Therefore, in the context of this paper, the concept of remixing refers to someone creating and taking a different photograph, however, still using a balance of the key separate aspects from the creative identity they were inspired by in the creative community of photographers. Being constantly inspired by other creative identities helps to create our own creative identity, as every new idea is simply a remix of things seen before. Although a creative’s identity may be developed through the identities of others, what is unique about each individual identity is their talent. One’s creative identity is then formed through what they let into their life and then they become the sum of their inspirations (Kleon, 2012). As Goethe once said, “we are shaped and fashioned by what we love” (as cited in Kleon, 2012, p.11). Therefore, if no one ever imitates, or remixes, anything, no one will ever create anything. However, the idea behind being inspired by other creative identities is not to blatantly always do whatever they do and exactly as they do it. The idea is that in order to start creating one’s own identity, they steal from whatever inspires them and they choose only the things that stand out to them and then from there they begin to find their own identity and aesthetic. Therefore, one is not only taking ideas from those who inspire them, they are also taking from the way they think (Kleon, 2012).

One slowly becomes as good as the things they choose to surround themselves with and be inspired by. No creative ever truly knows who they are, ever. Every creative is consistently trying to create, and one learns and finds their own creative identity though copying and remixing others. If people waited until they found their identity before they started creating, they would never create anything and they would never find their identity. Creative identity comes from constantly being inspired by what is found in the creative community, and a creative identity is found by remixing another’s. The same is true about learning how to write, one needs to copy down the alphabet in order to put it together for what they eventually want to say. Then, at some moment in time, this imitation game turns to emulation, which is one step further into finding one’s own creativity identity and breaking into their own aesthetic (Kleon, 2012). As Francis Ford Coppola once said, “We want you to take from us. We want you, at first, to steal from us, because you can’t steal. You will take what we give you and you will put it in your own voice and that’s how you will find your voice. And that’s how you begin. And then one day someone will steal from you” (as cited by Kleon, 2012, p. 37). However, whatever the case, as quoted by Kleon (2012, p. 34), “the human hand is incapable of making a perfect copy” and therefore, a creative’s identity cannot be weakened as those who are inspired by it are only ever remixing it.

Case study – Dominique Davis

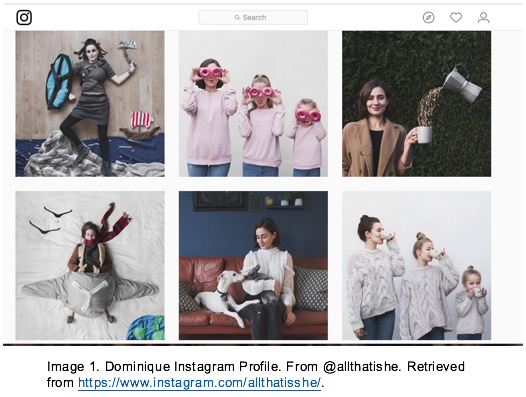

Finally, after discussing how a creative’s identity cannot be weakened by social media in the online creative communities because of the concepts of originality and remixing, one Instagram photographer can be used as a case study to specifically demonstrate how the concepts of originality and remixing can be used to prove that social media has not weakened a creative’s identity in the creative communities online. The one Instagram case study will be Dominique Davis, @allthatisshe. Her very well-known Instagram photographer identity will be discussed and then will be compared to another smaller, less well-known Instagram photographer, in order to show how one’s creative identity cannot be weakened through creative communities on social media.

Dominique Davis, @allthatisshe, is a content creator, Instagram coach, and writer who lives in Durham, United Kingdom. She has a very specific creative identity is very well-known for her creative photographs, especially those involving her and her two daughters together, dressed up very similar and doing the same thing, as shown in the screenshots below.

Below is the less well-know Instagram photographer Sina, @happygreylucky. Her Instagram profile can be accused of being a copy of Dominique’s due to pointing out a few similarities, thus weakening Dominique’s creative identity. However, due to the fact that nothing is original and within the creative communities, people remix other ideas and make them into their own, it can be said that Sina does not weaken Dominique’s creative identity or who she is on Instagram, but in fact has her own unique creative identity on Instagram.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it has been discussed within the various creative communities online whether or not the extensive nature of social media has weakened a creative’s identity within these creative communities. However, through discussing the concept of a creative community and the concept of creative identities as well as the concepts of originality and remixing, it can be said that this is not the case. Creative communities are places were people who are creative share common interests. Creative identity refers to the aesthetic and style a creative uses to distinguish themselves from each other. Due to concept of originality, it can be said that no identity is original and because of this, no identity can be weakened as a creative’s identity has always been formed through someone else’s ideas or concepts. Due to the concept of remixing, it can also be said the social media has not weakened a creative’s identity in creative online communities, as one is simply using another’s way of thinking to create their own, and therefore, this process of remixing cannot weaken someone’s creative identity or who they are within a creative community online. All these point were also demonstrated through using Dominique Davis, @allthatisshe, as a case study and by comparing her creative identity to another seemingly similar creative identity within the photographic creative community on Instagram. It was seen that these two profiles in no way weakened the other’s identity, even though similarities could be pointed out. In the end, that is the whole idea behind being in a creative community: to inspire and be inspired. Therefore, rather than weakening creative identities in creative communities, social media has only created an even bigger platform for people to be inspired and then in turn strengthen and grow their own creative identity. After all, as Pablo Picasso once quoted, “Art is theft” (as cited by Kleon, 2012, p.1).

Reference List

Boyd, D. M. and Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communications, 13(1), 210-230. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x.

Davis, D. (2018). Dominique Instagram Profile [Screenshot]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/allthatisshe/.

Fearon, J.D. (1999). What is Identity (as we now use the word)?. Retrieved from https://web.stanford.edu/group/fearon-research/cgi-bin/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/What-is-Identity-as-we-now-use-the-word-.pdf.

Glaveanu, V. P., and Tanggard, L. (2014). Creativity, identity, and representation: Towards a socio-cultural theory of creative identity. New Ideas in Psychology, 34, 12-21. Retrieved from https://business-institute.dk/media/1193/vlad-lene-2014.pdf.

Good Reads. (2018). Anton Chekhov: Quotes. Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/400240-there-is-nothing-new-in-art-except-talent.

Kleon, A. (2012). Steal Like an Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=3418972&query=steal+like+an+artist+austin+kleon.

Merchant, G. (2006). Identity, Social Networks and Communication. E-Learning, 3(2), 235-243. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2304/elea.2006.3.2.235.

Oxford Dictionary. (2018). The definition of ‘aesthetic’. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/aesthetic.

Oxford Dictionary. (2018). The definition of ‘community’. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/community.

Oxford Dictionary. (2018). The definition of ‘creative’. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/creative.

Oxford Dictionary. (2018). The definition of ‘identity’. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/identity.

Oxford Dictionary. (2018). The definition of ‘remix’. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/remix.

Pearson, E. (2009). All the World Wide Web’s a stage: The performance of identity in online social networks. First Monday, 14(3). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/2162/2127.

Simonton, D.K. (2016). Defining Creativity: Don’t We Also Need to Define What is Not Creative?. Journal of Creative Behaviour. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.dbgw.lis.curtin.edu.au/doi/10.1002/jocb.137.

Sina. (2018). Sina Instagram Profile [Screenshot]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/happygreylucky/.