Abstract

While much social research has been dedicated to how the Internet generally, and social networking sites specifically, enable people to connect across great distances, little attention has been paid to the impacts of these technologies on more local communities other than to suggest a negative correlation between online communications and neighbourly behaviour. This paper explores how the locally-focused social media platform Nextdoor supports theories that contend social networking sites’ unique affordances have the potential to support connection and engagement within communities – in this case, local communities specifically – unlike any that has been observed since the beginning of the industrial era. While this has resulted in positive effects such as enhanced community safety and providing for vital assistance to those in need during times of crisis, it has simultaneously facilitated repressive behaviours such as racial profiling, and the rapid spread of misinformation with dire implications for public health. The observations discussed here support the position that, while technology can empower participants’ capacity to connect and engage with each other, it is only how the participants choose to behave which will determine the social impacts of this engagement.

Introduction

As the Internet’s user base has increased around the world, online social networking platforms have grown and evolved, increasing the scope for communication on a global scale. However, while there has been a great focus on the Internet’s ability to connect people across great distances, research has often neglected to investigate how social networking sites are used in a more local context (Hampton & Wellman 2003, p. 278; Page-Tan, 2021, p. 2223). In fact, many scholars, such as Sherry Turkle (2016; 2017) and Taylor Dotson (2018) have maligned a supposed ‘decline in neighboring as people get drawn into online interactions’, suggesting that online communication is fundamentally antithetical to local community building (Hampton & Wellman 2003, p. 284; Hampton & Wellman, 2018). In contrast, sociologists Keith Hampton and Barry Wellman have long argued that social networking sites ‘afford many types of community, including neighboring’ (2003, p.284) and that ‘[s]ocial media is fostering networked, supportive, persistent, and pervasive community relationships’, including in a local context (2018, p. 649). The social networking site Nextdoor, established in 2011, focuses specifically on connecting people within their local neighbourhoods, and demonstrates how pre-existing local communities can use social media to build and strengthen ties. However, it also illustrates the potential downside of the changes to the ‘fundamental nature of community’ that Hampton and Wellman argue is occurring in the wake of recent technological changes, leading to increasingly insulated, segregated and repressive behaviours within local communities (Hampton & Wellman, 2018).

The community question

Since its inception, much discussion about the Internet’s social impact has centred around the ‘community question’, a ‘debate about how large-scale social changes affect ties with friends, neighbors, kin, and workmates’ (Hampton & Wellman, 2003, p. 278; Hampton & Wellman, 2018; Wellman, 1979). Hampton and Wellman identify three key fears at the heart of this debate: ‘[t]he weakening of private (interpersonal) community’ including reduced social contact with neighbours, ‘[d]isengagement from the neighborhood’, and ‘[t]he decline of public community’ including less civic involvement and less commitment to community (2003, p. 278). According to Wellman and co-author Lee Rainie in their book Networked: The New Social Operating System, ‘[t]he basic argument is that community is falling apart because internet use has led people to lose contact with authentic in-person relationships as they become ensnared online in weak simulacra of reality’ (Rainie & Wellman, 2018, p. 118).

While it has recently been framed around Internet use, this is far from a new argument. Similar fears have been expressed around various social and technological changes since the beginning of the industrial revolution, often focusing on those technologies that connect people in new ways, such as railroads, radio, and television (Rainie & Wellman, 2012, p. 117). As Hampton & Wellman identify,

part of contemporary unease comes from a selective perception of the present and an idealization of other forms of community. There is nostalgia for a perfect form of community that never was. Longing for a time when the grass was ever greener dims an awareness of the powerful stresses and cleavages that have always pervaded human society.

Hampton & Wellman 2018, p. 644

In demonstration of this, Rainie & Wellman note that Wellman’s sociological studies in the East York area of Toronto, Canada, found that few residents had strong ties with their neighbours. These studies were published in 1968 and 1979, decades before public access to the Internet became widespread (Rainie & Wellman, 2012; Wellman 1979).

Networked publics and persistent-pervasive communication

Far from being detrimental to community, computer-mediated communication can be seen to have significantly expanded opportunities for community building. danah boyd presents the concept of ‘networked publics’; publics – a collection of people who share a common understanding of the world, identity, or interest; locally or broader – that are restructured by networked technologies (boyd, 2010, 39-40). boyd describes these networked publics as being both ‘the space constructed through networked technologies’ and ‘the imagined collective that emerges as a result of the intersection of people, technology, and practice’ (boyd, 2010, p. 39). She notes that while they share much in common with other types of publics, the influence of technology introduces four distinct affordances: persistence, replicability, scalability, and searchability (boyd, 2010, pp. 39 & 48).

Keith Hampton builds on the work of boyd and others to present a theory of ‘persistent-pervasive community’ which is currently emerging, and is made possible by the affordances of social media (Hampton, 2016). Like boyd, Hampton focuses on the fact that communication on social media is persistent – automatically recorded and archived, allowing for asynchronous communication and searchability – and pervasive, providing for an ambient awareness of the interests, locations, opinions, and activities of their social ties in a way direct, one-to-one communication does not allow for (boyd, 2010, p.48; Hampton & Wellman, 2003; Hampton, 2016, p. 119). Hampton argues that these factors result in a structure that ‘resembles a hybrid of preindustrial, and urban-industrial, community structures’ (Hampton, 2016, p. 103). He states:

We are entering a period of metamodernity that renews many of the constraints and opportunities of the premodern community structure without discarding all of the affordances of mobility that have perpetuated through late modernity. Not since the rise of modern, urban-industrial civilization has there been the potential for such a significant change to the structure of community.

Hampton 2016, p. 103

Thus, the ‘community that never was’, where members have a pervasive awareness of their peers’ lives akin to that experienced by pre-industrial villagers, but in a modern context, is possible – and, indeed, emerging – in the wake of social media technologies (Hampton & Wellman, 2018, p. 644; Hampton, 2016). With its focus squarely on the hyperlocal neighbourhood community, no social media platform provides as clear an example of this as Nextdoor.

Nextdoor

Nextdoor was launched in 2011 as ‘the first private social network for neighborhoods’ (Lambright, 2019, p. 87). The company states that its mission is ‘to provide a trusted platform where neighbours all over the world can work together to build stronger, safer and happier communities’ (Nextdoor, 2018, para. 2). Initially focused on the developers’ own local region of the San Francisco bay area, it has expanded across the US and worldwide, with the Australian launch taking place in October 2018 (Nextdoor, 2018). Their promotional material focuses on the same imagined nostalgia discussed previously, with references to neighbourhood barbecues, trick-or-treating and ‘online chats that lead to more clothesline chats’ (Lambright, 2019, p.89). Co-founder and former CEO of Nextdoor, Nirav Tolia, declared that, ‘[w]e created Nextdoor to bring back a sense of community to the neighborhood and help create safer, stronger places to call home’ (cited in Nextdoor, 2012, para. 7).

We created Nextdoor to bring back a sense of community to the neighborhood and help create safer, stronger places to call home.

Nirav Tolia, founder

Unlike other social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter, Nextdoor users must not only use their real name while using the site, but also verify their residency in a specific neighbourhood, either through geolocation technology, being vetted by a neighbour who is already an approved member, or by submitting evidence to the company (Kurwa, 2019, p. 113; Page-Tan, 2021). Once admitted, users can only see content within their own neighbourhood or those directly bordering it (Kurwa, 2019, Lambright, 2019). These constraints aside, Nextdoor functions similarly to other social networking sites, with features including a personalised news feed; adding friends; the ability to post text, images or videos, and comment on the post of others; direct messages; and interest-based groups (boyd & Ellison, 2007, Kurwa, 2019). However, its hyperlocal focus puts it in stark contrast to most other social networking sites, with their focus on the ability to access wider communities, and to connect and re-connect over long distances (Lambright, 2019, Mosconi et al., 2017, p. 960).

Hyperlocal electronic communication networks

While Nextdoor, as a purpose-built platform for local communities to connect, is somewhat unique among current prominent social networking sites, there is a long history of locally-focused electronic communication networks, even pre-dating the Internet. The earliest examples included networked computer systems situated in public libraries and other public places within a local area, which were later superseded by electronic bulletin boards, discussion forums, local email lists and listservs (López et al., 2017, p. 3). User-created and -managed groups within larger social networking sites such as Facebook also emerged, and continue to be popular in many localities (López et al., 2017; Mosconi et al., 2017).

Communities as fluid personal networks

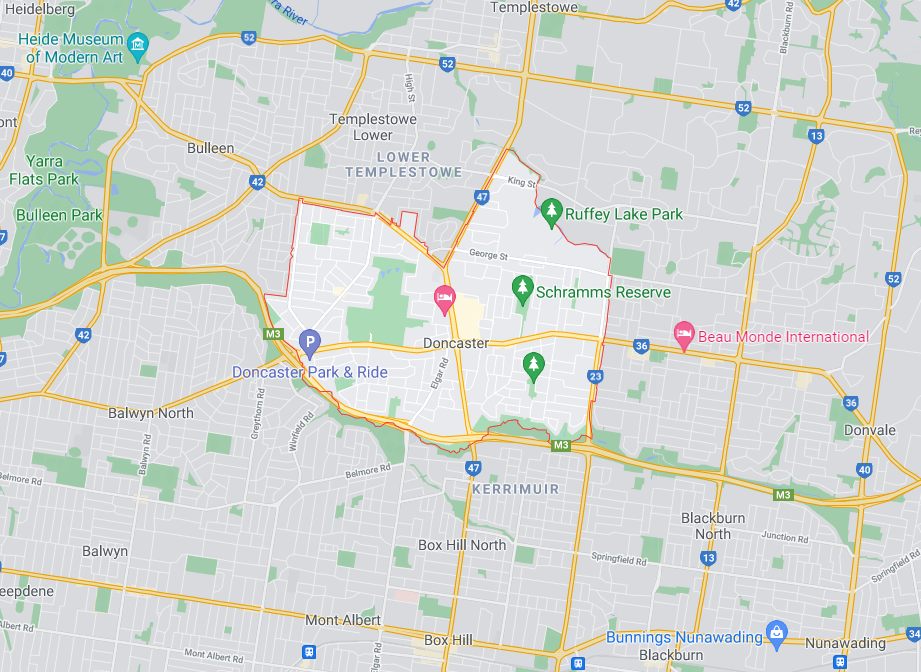

Nextdoor differs from these other examples of hyperlocal social networks, however, in one key way. While each of the networks described above is a discrete, self-contained group focused entirely on one specific place, Nextdoor, as mentioned previously, allows visibility across adjoining suburbs. For example, I am able to see activity within my own suburb of Doncaster, Victoria, and all the suburbs that directly surround it, and anything I post is visible to residents of those suburbs (Page-Tan, 2021). However, if I am to comment on a post made by a resident of the suburb directly to the west of my own, Balwyn North, this can then be seen by residents of all suburbs adjoining Balwyn North, including those areas that do not abut Doncaster. Similarly, I will be able to see content posted by residents of Doncaster East, but residents of Balwyn North will not.

In this way, my social network within Nextdoor is different to, but has overlap with, that of those in nearby areas. As Rainie and Wellman note,

It helps to think about communities as fluid personal networks, rather than as static neighborhood or family groups. For too long, the model of community has been the preindustrial village where people walked door to door and all knew, supported, and surveilled one another. These bygone village groups have largely transmuted into multiple, fragmented personal networks connected by the individuals and households at their centers.

Rainie & Wellman, 2012, p. 6

This can be seen, through the example above, to be true in even the most hyperlocal of social media. This distinguishes Nextdoor from its predecessors, which, while featuring some of the affordances of a networked public, do so to a lesser extent, particularly in regard to scalability (boyd, 2010).

It is this potential for scalability that is one of the most noteworthy ways in which Nextdoor exemplifies the ‘period of metamodernity’ presented by Hampton (2016, p. 103). As Hampton and Wellman note, offline relationships between suburban neighbours rarely extend more than a few houses away:

Local social ties rarely extend around corners or down the block. The limited range of local ties has the effect of limiting residents’ familiarity with others in the community. In turn, this generates low levels of community solidarity, limits neighborhood surveillance, and reduces attachment to the broader neighborhood.

Hampton & Wellman, 2003, p. 297

Hyperlocal social media such as Nextdoor, then, has the potential to create the imagined ideal suburban community more effectively than offline ties between neighbours alone. This has the potential to result in ‘an increased awareness of and engagement in both online and offline spheres’ (Mosconi et al, 2017, p. 962).

Surveillance for safety – and exclusion

The neighbourhood surveillance alluded to by Hampton and Wellman above has become one of the most popular features of Nextdoor. While it was initially created with the intention of being ‘a hyperlocal Yelp or Craiglist’ according to Tolia (as cited in Lacy, 2013, para. 30), it quickly became popular for its potential safety and crime prevention applications. Neighbours can report crimes or other safety concerns in the area among themselves using Nextdoor in a way that is far more effective than in person or relayed one-to-one communication such as phone calls and text messages (Lacy, 2013). The persistent-pervasive nature of the medium affords not only the immediacy and scalability of the initial message, but also the capacity for it to be referenced at a later date: with the benefit of an archive of community-sourced information, neighbours can note patterns in strange or concerning occurrences, and new residents in an area can quickly become aware of common local issues (Hampton, 2016). As Hampton notes, ‘[p]ervasive awareness brings us full circle in the advent of surveillance’, allowing for a return to the local awareness levels of the pre-industrial village, within a larger urban or suburban area and population (Hampton, 2016, p. 114).

But it is this same capacity for neighbourhood surveillance that has resulted in a persistent and concerning issue of racial profiling on Nextdoor (Lambright, 2019). In 2015, it was reported that residents in Oakland, California would frequently post on Nextdoor regarding unsubstantiated ‘suspicious behaviour’ by black residents, salesmen and mail carriers for ‘walking down the street, driving a car, or knocking on a door’ (Kurwa, 2019, p. 111). In a country with a long history of racial segregation and unrest, Rahim Kurwa argues that white users of Nextdoor in the United States use it as ‘a tool to build a digitally gated community’; a historical ‘site of race and class exclusion enforced through private policing’ whereas ‘today digitally gated communities achieve these ends through social policing’ (Kurwa, 2019, p. 112). This aligns with the broader social network research of boyd and Nicole Ellison, who argue that ‘it is not uncommon to find groups using [social networking] sites to segregate themselves by nationality, age, educational level, or other factors that typically segment society’ (2007, p. 214), and Hampton and Wellman, who warn that ‘repression and constraint…can come from closed networks’ (2018, p. 644).

Crucial connections – and misinformation – in the time of COVID-19

While the negative social impacts of the kinds of persistent and pervasive surveillance afforded by a hyperlocal social network should not be understated, there have undoubtedly been benefits to the local ties created and reinforced within Nextdoor as well. The ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic has given the platform a new relevance and increased popularity, with its capacity for immediacy and reach of information, along with searchability, making it an ideal channel for local discussion around obtaining and sharing resources, trading favours, and reaching out to vulnerable members of the community (Koeze & Popper, 2020; Mosconi et al., 2017; Page-Tan, 2021). For elderly people, the pandemic has presented not only a significant health concern but also social isolation, and while connections through any social media is able to provide relief from loneliness, the connections made through Nextdoor with neighbours can help to fulfill other needs such as access to food, medication and transport (Brooke & Clark, 2020; Brooke & Jackson, 2020).

However, use of Nextdoor during the pandemic has also had problematic effects, with mass distribution of misinformation about the virus and vaccine leading the developers to include new barriers to posting, with any health-related content now prompting the poster to consider whether it is in line with medical advice before publishing (O’Brien, 2021).

Conclusion

While local communities’ use of Nextdoor can be seen to have been both beneficial and detrimental, it is ultimately the communities themselves, and not the platform, which are responsible for these social effects. As boyd notes, [n]etworked publics’ affordances do not dictate participants’ behavior, but they do configure the environment in a way that shapes participants’ engagement’ (2010, p. 47). With its hyperlocal focus, Nextdoor provides a particularly cogent demonstration of Hampton’s new era of persistent-pervasive community, and demonstrates how social media combines both the constraints and opportunities of the pre-industrial village with those of late modernity (Hampton, 2016, p. 103). Nextdoor provides powerful opportunities for engagement within local neighbourhoods that comes as close as contemporary society ever has to achieving that perfect community that never was, but only the behaviour of the community’s members can determine if this is for better or for worse.

References

boyd, d. (2010). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A Networked Self (pp. 39–58). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876527-8

boyd, d, & Ellison, N. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 13(1), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Brooke, J., & Clark, M. (2020). Older people’s early experience of household isolation and social distancing during COVID-19. Journal of clinical nursing, 29(21–22), 4387–4402. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15485

Brooke, J., & Jackson, D. (2020). Older people and COVID-19: Isolation, risk and ageism. Journal of clinical nursing, 29(13–14), 2044–2046. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15274

Dotson, T. (2018). Technically together: Reconstructing community in a networked world. MIT Press.

Hampton, K. N. (2016). Persistent and pervasive community: New communication technologies and the future of community. American behavioral scientist, 60(1), 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764215601714

Hampton, K., & Wellman, B. (2003). Neighboring in Netville: How the Internet supports community and social capital in a wired suburb. City & community, 2(4), 277–311. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1535-6841.2003.00057.x

Hampton, K. N., & Wellman, B. (2018). Lost and saved . . . again: The moral panic about the loss of community takes hold of social media. Contemporary sociology, 47(6), 643–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306118805415

Koeze, E., & Popper, N. (2020, April 7). The virus changed the way we Internet. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/07/technology/coronavirus-internet-use.html

Kurwa, R. (2019). Building the digitally gated community: The case of Nextdoor. Surveillance & Society, 17(1/2), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12927

Lacy, S. (2013, January 22). Nextdoor’s unexpected killer use case: Crime and safety. Pando. https://pando.com/2013/01/22/nextdoors-unexpected-killer-use-case-crime-and-safety/

Lambright, K. (2019). Digital redlining: The Nextdoor app and the neighborhood of make-believe. Cultural critique, 103(1), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1353/cul.2019.0023

López, C., Farzan, R., & Lin, Y.-R. (2017). Behind the myths of citizen participation: Identifying sustainability factors of hyper-local information systems. ACM transactions on Internet technology, 18(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1145/3093892

Mosconi, G., Korn, M., Reuter, C., Tolmie, P., Teli, M., & Pipek, V. (2017). From Facebook to the neighbourhood: Infrastructuring of hybrid community engagement. Computer supported cooperative work (CSCW), 26(4–6), 959–1003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9291-z

Nextdoor. (2012, August 6). Nextdoor survey shows over two-thirds of homeowners feel safer when they know their neighbors [Press release]. https://au.nextdoor.com/press/20120806/

Nextdoor. (2018, October 30). Nextdoor, the world’s largest private social network for neighborhoods, launches across australia [Press release]. https://about.nextdoor.com/nextdoor-the-worlds-largest-private-social-network-for-neighborhoods-launches-across-australia/

O’Brien, S. (2021) People are turning to Nextdoor for tips on getting a vaccine. Why that may be a problem. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/05/tech/nextdoor-pandemic-sarah-friar/index.html

Page-Tan, C. (2021). Bonding, bridging, and linking social capital and social media use: How hyperlocal social media platforms serve as a conduit to access and activate bridging and linking ties in a time of crisis. Natural hazards, 105(2), 2219–2240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04397-8

Rainie, L., & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The New Social Operating System. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8358.001.0001

Turkle, S. (2016). Reclaiming conversation: The power of talk in a digital age. Penguin.

Turkle, S. (2017). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other (third edition) (3rd ed.). Basic Books.

Wellman, B. (1979). The Community Question: The intimate networks of East Yorkers. American Journal of Sociology, 84(5), 1201–1231. https://doi.org/10.1086/226906

Hey Nakia,

I wasn’t aware of Nextdoor before reading your essay, but I’m happy I do now. This was a really interesting paper about a social media platform that is operating quite uniquely from the more popular platforms like twitter, Facebook and Instagram. As you address in your discussion Nextdoor is focused on building hyper-local connections between members of geographic communities where as most other platforms focus on making as many connections between people as possible regardless of the distances between them. I think Nextdoor is really refreshing in this regard and I’m pretty interested in checking it out. I feel like so many people are becoming over-reliant on their online social interactions which is having the effect of stunting their ability to form real-world relationships. Nextdoor could be an important solution for this as it uses the internet as a means to establish real-world connection instead of as a means of replacing them. But I’ll have to look into it myself. Have you been a user of Nextdoor for a while? And do you have any tips for someone starting off on the platform?

Cheers.

P.s. In my paper I discuss the online incel (involuntary celibate) community is having the effect of radicalising its member with misogynistic ideology, here’s a link if you’d be interested in having a look: https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2021/2021/04/27/misogynistic-radicalization-of-users-in-the-online-incel-community/#comment-1286

Hi Cameron,

I was going to object to your contention about people becoming over-reliant on online social interactions but then I saw what your paper was about and – yeah I can see why you’ve come to that conclusion after researching that particular group! I suppose it definitely can happen, but I think connections made online can also be really valuable. For what it’s worth I met my partner of ten years on Twitter of all places, although interestingly enough it was due to our connections in the Perth twitter community, so there was that local connection again.

I joined Nextdoor about a month before writing my paper, and it’s been a really nice experience so far, with a lot of opportunities for making offline connections. As for tips for starting off on the platform – I guess I would say, following on from my discussion with Thomas Kelly below, to maybe be a bit skeptical of how much the app encourages you to give up anonymity and privacy. My lack of a real last name on the app has not stopped me from making friends, connecting with people offline, and accessing helpful information about my neighbourhood. And following on from Silas’s comments below – be brave and speak up when you see prejudice from other users!

Wishing you well on your Nextdoor adventure, I’d love to hear how it goes!

Your paper offered a very different perspective by focusing on a hyperlocal form of social media, and I think you did a great job Amanda. I am on Nextdoor myself, but don’t use it very often. I found your paragraph about racial profiling particularly interesting, as it’s something I’ve seen occur. Not on Nextdoor, but within my suburb’s community Facebook group. In several instances, people who have posted about “suspicious individuals” are really just posting about people of colour who they have stereotyped, and most commonly Aboriginal Australians. I’ve seen those kind of posts go unchallenged, and some of them are called out, but either way the perpetuation of racial stereotypes has occurred.

Thanks Silas! I’m sorry to hear that you’ve seen racial profiling on your suburb’s Facebook page. The more I hear of others’ experiences the luckier I feel about my own, including on a couple of local Facebook pages I’ve joined since this conference started.

It can be really hard to be the one who challenges those sorts of posts, especially since it seems like, a lot of the time, the person who speaks up gets blamed with “causing conflict” rather than the person who said the inflammatory thing in the first place.

Hello!

Like most of the others – I also have never heard of Nextdoor before. So, it is a credit to you that I feel quite knowledgeable about the platform now, and understand its limitations. It seems like the app is much more integrated in America than where I live in Australia (or I have simply been living under a rock).

Personally, I agree with a lot of the benefits of this app. It would reduce my need to be following so many different community groups on Facebook and have a dedicated space for all of it. However I would still be hesitant to join it for fear of an unsafe space being created, especially in a third place where so many people will know the area where I live. Would you say that NextDoor could interest sufficient enough safety measures to assist with anonymity and confidentiality?

Hi Thomas,

Thanks so much for your comment, and your very kind words. It’s been heartening to hear that I’ve been able to sufficiently explain the platform to the uninitiated in such a short word limit!

I was also concerned about anonymity and confidentiality when I signed up, so I definitely see where you’re coming from. The combination of the unknown audience, as discussed by boyd as one of the implications of a networked public, with the fact that this audience is in the same geographical area, means that the potential danger from anyone with malicious intentions is increased.

Personally, I got around this by not using my real full name, and have been careful not to share any photos which might show my exact location, since a local landmark is visible from my backyard. But this is in direct defiance of instructions and suggestions given by the app (they even suggested posting photos to see if neighbours could guess where they were taken – fine if in the local park, not so much if they help triangulate a naive participant’s location).

I think that in many ways it’s in the interests of social media companies not to provide those safety measures, sadly. Karla’s paper on real name policies offers some great insight into this: https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2021/2021/04/26/whats-in-a-name/ So sadly it’s up to us as users to remain vigilant, and protect our own safety.

Are there any specific safety measures you had in mind? I’d love to know if you have any ideas that might be in both the company and the user’s interests.

I really enjoyed your paper and like some of the other comments I have not heard of Next door until now. I live in a very private area of Perth and I do not even know my neighbours. They are all professional and, in the city,, we tend to keep to ourselves.

I thought your discussions on hyperlocal and in this present time is remarkably interesting and providing a way for people to connect to each other. How do you think next door can improve on their affordances and introduce policies so that people will be able to feel more confident about using this platform and to provide a better community within the platform?

With citizens online behaviours, this is a concern as citizens are voicing their concerns more freely and thinking that is not any consequences. Communities are forming because citizens are connecting with others who feel the same on political views. In my paper our discuss how online communities have changed and how this will affect citizens online behaviours.

https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2021/2021/04/26/facebook-and-twitter-have-become-a-third-space-for-citizens-to-have-freedom-of-expression-on-politicalviews/

Hi Nakia,

Thanks so much for your comment! I also don’t know my neighbours where I am, and am not a particularly social person, but when I found out that Nextdoor was in my neighbourhood now, I felt weirdly compelled to join. I guess that desire for the pre-industrial village-type connections runs deep.

In response to your question – I’ve been pleased to see that Nextdoor do actually seem to have more of a social conscience than some other social media companies, and they have actively worked to try to counteract some of the problems with the platforms by changing their interface and messaging. One example of this is that after they become aware of racial profiling issues in Oakland, the founder and then-CEO Nirav Tolia sent out this press release, clearly condemning the practice and stating what they were going to do to prevent it: https://blog.nextdoor.com/2015/10/15/racial-profiling-the-opposite-of-being-neighborly/

Changes that were put in place include, as the press release says, a way to report messages for racial profiling, a warning screen with messages about best practices, a change to their member guidelines, and a commitment to continue educating members. How this worked in practice is explored in detail in this article: https://www.wired.com/2017/02/for-nextdoor-eliminating-racism-is-no-quick-fix/

Obviously what they have done hasn’t fixed it entirely, but they are clearly working on it actively which is great to see. Similar changes to the app’s interface were made when it became clear the app was being used to spread COVID-19 misinformation as well. I don’t think they’ll be able to entirely fix the problem of malicious users, but their focus on education is a good one, I think.

Your paper sounds very interesting, I look forward to reading it!

Thanks for the response. I guess when citizens behaviour changes and technology changes then there is always the need to re-change your programs and constantly keep up with it.

I have learnt quite a few things and I will investigate this for my own safety and understanding.

Thanks so much for sharing and your knowledge about this has been fantastic and you really have done your research on this.

So good to work with you again and I am sure we will be in another unit again.

Nakia

Nakia, it looks like something weird has happened with your URL here and it goes to a broken link. Just FYI for anyone else wishing to read Nakia’s paper, the correct link is: https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2021/2021/04/26/facebook-and-twitter-have-become-a-third-space-for-citizens-to-have-freedom-of-expression-on-political-views/

oh thanks for that. Much appreciated.

Amanda, great paper! In my personal situation, I am not sure I would receive any benefits from Nextdoor. Hampton and Wellman (2003) do not apply to me, as I do not live in a suburb. I live in a small regional town with a population of less than 2,000 people total. Our social ties really do extend around corners, and further! While I do not know everyone living in our town, there must be at least one person I know personally living on each street in town. Eight years here has enabled me to recognise most people who shop in the local supermarket and put me on speaking terms with probably a third of these. As Joseph Dobson commented, we also have a local Facebook group. With such a small population, we can usually find any local information we need here. It seems to me that Hampton’s (2016) theory of “persistent-pervasive community” also applies to our local Facebook group/s.

As you know (thanks for your comments!) I talk about misinformation in my conference paper too. While researching my paper I stumbled upon this article by O’Brien (2021): https://edition.cnn.com/2021/03/05/tech/nextdoor-pandemic-sarah-friar/index.html which details how shady characters have taken advantage of Nextdoor users’ connecting over vaccine appointments to run phishing scams. In contrast, this article by Simony (2021): https://www.9news.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/vaccine/covid-misinformation-nextdoor/73-d2ea78e7-a348-46ef-8aec-d27d6c33f001 shows how Nextdoor users’ have been led astray by misinformation to distrust legitimate organisations trying to connect people to vaccine appointments. Nicest of all, this article by Page (2021): https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2021/02/24/covid-vaccine-stranger-nextdoor/ demonstrates how a desperate woman managed to obtain two potentially lifesaving vaccine appointments prior to her open heart surgery, thanks to the kindness of a total stranger that she connected with over Nextdoor. Such a heart-warming story! I think these examples beautifully support your conclusion that the benefits of Nextdoor are dependent on the behaviour of their users.

Hi Karena,

Thanks so much for your comment! It’s great to get a perspective from someone living in a much smaller community. I’m curious as to what kind of posts are most common on your local Facebook group?

Thanks for sharing those articles. I did read the O’Brien article thanks to a recommendation on Blackboard (maybe from you?) but hadn’t seen the other two. That second one is particularly interesting in the context of our earlier discussion about combatting misinformation/disinformation. It serves as an important reminder that for all the benefits of critical thinking and skepticism, there is perhaps such a thing as being *too* cautious in a way that can be detrimental. It’s just as important to be able to identify a trustworthy source as it is to be suspicious of untrustworthy ones.

Hello, Amanda. Thank you for your quick reply! Surprisingly, for a small town, we have two local Facebook groups. Both are private groups, with new members approved by existing members or administrators. The majority of posts are buy, sell and wanted posts. We can find it hard to get good tradespeople to visit us here, so there are often requests for recommendations. The Discussions are a mix of everything else – local events, employment, community group updates, accommodation requests, promotions by local businesses, notifications about stray pets. Crime and suspicious behaviour are pretty rare around here, but all crime except domestic disputes is usually shared to Facebook if it occurs. If I want to research someone local, our Facebook groups are a good place to do so. I feel this fits in with Hampton’s (2016) theory of “persistent-pervasive community”. What do you think? To me, Nextdoor sounds like it provides similar content. Do you agree? What content or affordances does Nextdoor provide that are significantly different?

I had not shared the O’Brien (2021) article previously, so cannot accept credit for that. Reading it was actually the first time I heard about Nextdoor. “It’s just as important to be able to identify a trustworthy source…”. What a great summary! There is so much misinformation on SNSs that some days I feel like I need to research all the “factual” information I see. Personally, I believe most people in the world are “good” people who have no intention of hurting anyone, but the easily available anonymity of online profiles and the inability for me to “read” the body language of a poster on SNSs means I am much less trusting of people online than in person. Do you feel the same? Regards, Karena

Hi Amanda,

Congratulations on your excellent paper. I thought your paper was really well written, and your picture choice really added a level of connection to your article.

I also had never heard of Nextdoor, but your paper outlines the great use of a platform to creating and enhance a hyperlocal community. While I have not used Nextdoor, I am in a similar localised social media community group via Facebook. Your article encapsulates a lot of the characteristics I see in this group, both positive and negative.

I live in an inner-city suburb in Sydney, and our neighbourhood has a Facebook group for members of our postcode. As you point out, this group is static in terms of accessibility, being a private group access requires vetting by a member, therefore not making it easily accessible and beneficial for all members of the neighbourhood.

Something I have noticed about this group is that location seems to work well to connect people surrounding immediate local events (roadworks, power outages). But when location is the main category to amalgamate people, the commonality of social views can be limited. There is often disagreement within this group, when it comes to opinions about broader community and societal issues.

Well done on a great contribution to the conference.

Hi Joseph,

Thanks so much for your comment! It was a real pleasure to read your paper and I am grateful to have your input on my own.

That’s a great point, that people unified by location very often don’t have much else in common these days. In the pre-industrial village they would have, but now location seems to have so much less bearing on our lives, thanks to innovations from the railways to the Internet. Maybe it’s misguided optimism that makes people seek out those connections, but as you say, it is very useful for distribution of very local, very up-to-date information if nothing else.

This weekend I pruned my apple tree to give the branches to a rabbit that lives in a nearby suburb. I never would have even known rabbits liked such things, but I’m glad I was able to provide them – and have now been promised photos of the rabbit enjoying the branches! I really do love these little interactions and connections it affords, even among all the negatives.

Was the rabbit connection made via Nextdoor? Regardless it’s a great example of community connection. I have found that being a member of our online neighbourhood community has made me much more active in the offline community. Member regularly posts restaurant or bar recommendations, new shops or experiences that have come to the area, and I often, after reading these, head out and try them out. Members often do the same and then report back about their experiences in the comments of the post. In this element of the hyper-local online community, I see a real benefit for businesses and community members in the neighbourhood.

Yes it was, haha I should have specified that!

Your example is a great one for the positives of hyperlocal social media. Another one that’s currently happening in our area is a weekly meeting of people learning English who want to practice together, and native English-speaking volunteers have joined the group thanks to a post on Nextdoor. Despite my antisocial tendencies I’m tempted to go, it sounds like fun!

Hi Amanda!

Thanks for your paper, it was a really interesting read.

I think a lot of people yearn to feel like they are part of a community. I think localised social media platforms such as Netxdoor provide a perfect opportunity to provide this sense of community too.

Like you mention though, such a sense of community comes with it’s downsides and I feel like this is almost innately so when we look at it from a segregation perspective.

You mention examples of this under the guise of racial profiling, etc. but I would like to put forward the case of those who perhaps don’t yearn for the sense of community. Those who are happy to stay a bit reclusive and are not phased about whether or not they are a part of their local community. If say, one of these people were to move to a theoretical neighborhood where ‘everybody’ is on Nextdoor and who have managed to create the ‘perfect society that never was’, then the newcomer, being the recluse that they are, would almost immediately be segregated considering their lack of interest in such a community.

This could lead to that person being targeted by the community as a figurehead for mistrust and in turn a scapegoat for any mischievous occurrences within that community.

Considering the echo-chambered nature of community, do you think the scenario detailed above could occur?

Thanks again for your paper!

Hi Jordan,

Thanks for your comment, I really appreciate it!

What an interesting situation you propose! I think you’re right that this could absolutely happen, and have some really negative effects for that person as you propose – an “if they’re not with us, they’re against us” kind of mentality. Those effects could really compound if that person is unlike the rest of the community in some way, e.g. younger, of a different ethnicity, doesn’t have kids in an area full of families, etc.

What has happened in the US, that I didn’t have a chance to get into in detail in my paper, is that gentrifiers – people of a higher socioeconomic status coming into traditionally lower-class areas which are now becoming “trendy” – tend to be more easily able to access the Internet in general, and more likely to participate in online communities like NextDoor and local Facebook groups. So although they are in the minority, they are able to amplify their collective power by grouping together in these online spaces and promoting changes in the neighbourhood that suit their own interests rather than those of the people who have lived there for generations.

This becomes an even greater problem when you consider the way Nextdoor intends to eventually monetise its platform, which is by partnering with local governments and agencies, including the police. If these neighbourhood groups are dominated by one particularly vocal and well-organised sub-group, it can mean other neighbours are excluded from important messaging from local authorities and organisation who are paying to use the platform as a communication channel to their local area. Concerns about this are expressed by members of the Oakland City Council in a great article I didn’t end up referencing: https://www.wired.com/2017/02/for-nextdoor-eliminating-racism-is-no-quick-fix/

Thanks again for commenting, I really enjoyed reading your paper and appreciate you adding your perspective on mine. All the best for the rest of the conference!

Hi Amanda!

I find your paper thoroughly engaging, especially on a personal level, because I notice that we use similar sources and argue some similar points, but to different ends!

My primary argument focused on the broader concept of nationality, and an optimistic view of new community; I found your hyperlocal focus refreshing. Next Door has this contradictory quality of being a digital social network with a local focus, and almost seems unnecessary at first, but your analysis of it as a “fluid personal network” made for a fascinating viewpoint.

What I liked the most was a defense of new forms of social networks with analysis of the downsides of a specific one like NextDoor. All in all, great stuff!

You can check out my paper as we pretty much talk about very similar things but with different perspectives: https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2021/2021/04/26/social-media-and-the-re-structuring-of-communities-changing-perceptions/

Thanks so much for commenting, Anurag, and for your very kind words.

You’re right that a hyperlocal social networking site seems at first to be unnecessary, but I think the current global pandemic has really shown that there is a place for this kind of thing – if it can shed its racist reputation.

I’ve actually had your paper open in a tab for a few days, as your title and abstract really interested me. I look forward to reading it soon!

Thank you for the kind words Amanda. Looking forward to your comments!

Excellent analysis and well written!

I agree that whether the tool is used for positive or negative intent lies in the hands of the user.

‘The perfect community that never was’

Brilliant!

Thanks Liese 🙂 You’re too kind!

Hi Amanda,

I think this is really interesting! I’m currently based in the US, and like you mentioned the app definitely has a stronger grounding over here. I’m in a bit of a unique situation where the suburb I live in is pretty commercial and very close to the downtown part of the city, so my experiences might be different than someone in a more suburban area.

In my own experience, I know I only signed up for the app when I heard what I thought might be gunshots, and wanted to know what was happening. It quickly became apparent to me that in my area, NextDoor was primarily being used to police one another, particularly with regards to political signage in windows and “suspicious looking people” residents saw on the street. I quickly deleted the app, realising that it wasn’t so much a community, but a group of wary people trying to warn one another.

My own experience indicated that the demographic on NextDoor tended to skew a bit older. Do you think there’s a younger market that could be using NextDoor, and do you think that younger generations need or want a hyperlocal social media? I’ve moved around a lot in the last few years, so I often think about establishing and understanding the communities that I live in, but that’s something I usually seek from expat groups, rather than more local sources.

I’d love to hear about your experiences using the app in Australia, and why you think the older demographic tend to connect more deeply with NextDoor?

Hi Maddison,

Thanks so much for your insight, it’s very interesting! I’m sorry to hear you had such a bad experience with the app over there, but it sounds very much what I’ve read about in the research that exists so far.

My experience has been a lot friendlier, thankfully. My area does have a large older population, but it also has a majority overseas-born, non-English speaking background population, which may impact the way we as a community tend to embrace each other’s differences rather than fear the “other”. Everything in my area (that I’ve seen so far) has been about seeking or offering help, lost or found pets, and wardrobe clear-outs, exactly as I had hoped. There was a single crime-related post, about a garage break-in, but even that poster was remarkably empathetic of the thieves and noted that they hadn’t taken much and didn’t damage anything.

For the older people in my area, it’s been a real lifeline during COVID (we had a very long and strict lockdown in Melbourne) as they can connect with neighbours who can deliver groceries or medication when needed, and have people who are close by watching out for their safety. I’ve also seen many posts by older residents expressing gratitude for the local events they have found out about through Nextdoor, which have allowed them to make new, in-person friends at a time their children and grandchildren, and friends from other areas, may not be able to visit.

As for the younger generations, that’s a very good question. I recently finished reading danah boyd’s “It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens” and the overwhelming message of that book was that teenagers use social networking sites to connect with the people they already know and would prefer to be hanging out with in person if they were able to. Nextdoor is more about connecting strangers than existing friends, but it also has an emphasis on facilitating in-person catch-ups/exchanges as well, so it may be a welcome way to make, and maintain, new connections for younger people as they grow up and branch out of the neighbourhoods they grew up in, as long as it can shake off its racist, paranoid image.

Hi Amanda,

Loved reading this paper. I’d never heard of the Next Door app until now! I always wonder what makes a developer limit their subscribers by requiring referral to join up… do you think they do it so that members are less likely to be lurkers?

I liked your theory that the quality of interaction and positive use of platforms like Next Door is determined by the behaviour of the individuals who are using the product. Like you say, antisocial behaviours like racism, ostracisation of individuals, and generally judgmental behaviours were already prevalent in communities and villages in times past, and were probably worse because of the homogeneity of the inhabitants, the limited counter information available about things that were different, and the sense that there was no escape like there is these days in our digitally connected lives.

It was interesting reading about Next Door and comparing it to Facebook and reflecting on how that is too. There are community news groups, buy and sell groups for suburbs and city regions, marketplace, vigilante news sites. So much of the daily information coming through my feed also seems hyperlocal. Do you think humans are just naturally conditioned to be curious about the thins they now and are already connected to?

Hi Kymberly,

Thanks so much for your comment! I think you’re right; looking at it from an evolutionary perspective, we stayed in one place with the same small group of people for much, much longer than we’ve been connected on a wider scale.

As for why they restrict it so much – I think, for one thing, it helps avoid spam. Anecdotally I’ve heard from people in the US, where Nextdoor is much more popular, that people in multi-level marketing companies (pyramid schemes) will somehow get around the restrictions and advertise their wares across dozens of neighbourhoods at a time. I think it’s the GPS verification option that allows them to do this – it wasn’t mentioned in any of the articles I read, so is likely very new, and it wouldn’t be hard to drive around and claim to live at various addresses you stop in front of (maybe I should stop talking lest I give anyone ideas…).