Featured image: Morrison, T. (2018, March 14). Incredible moment on social media — East coast schools are walking out, calling on Congress to act on gun violence. @Snapchat’s @SnapMap feature visualising this movement in the most amazing way… [Tweet]. Retrieved from:

https://twitter.com/THETonyMorrison/status/973937933353934849

Abstract

Spatial metaphors were initially drawn upon to help users navigate and understand a new online world with the conception of the Internet. This urbanisation of the digital space has continued to persevere throughout the rapid rise of Web 2.0, with the geotagging of online content, defined by Fendi et al., (2014) as “the process of adding geographical identification metadata”, becoming the new way in which users could integrate their understanding of location to visualise, classify and represent their experience online. Checking-in to a location on Facebook, pinning a location to a photograph posted on Instagram, applying a geofilter on Snapchat, etc. have now become normalised online behaviour to supplement content posted online. These various location-based affordances of Web 2.0 social networking platforms have helped to create this physical spatial substitute and in doing so, supporting the formation of group identities and practices of online communities. This paper specifically looks at Snap Map, Facebook Marketplace and augmented reality gaming app, Pokémon GO and how their integration of location have helped facilitate the way in which users experience a Web 2.0 online world, as well as the implications of sharing this information online.

Keywords

Online communities, Snapchat, Facebook, Pokémon GO, geotagging, location, participatory culture.

Introduction

The conception of the Internet introduced new uses of language and terminology to help users navigate and understand this new online world. One such way was to draw upon spatial metaphors in order to conceptualise their experience. Users navigated this cyberspace as web surfers of an information “superhighway”, creating traffic as they visited various “home” pages at web “addresses”. Aroya (2014) posits that these spatial metaphors became useful instruments to help foster a deeper understanding of this digital realm, with mapping seen as a convenient way in which to visualise, classify and represent this digital landscape. This urbanisation of the digital space has persevered throughout the rapid rise of Web 2.0, which allowed the user to take on a more active role in the production of online content. In particular, the geotagging of online content, defined by Fendi et al., (2014) as “the process of adding geographical identification metadata”, was utilised to integrate location online. As of 2016, data from the Pew Research Center has found that nine out of ten smartphone owners have now enabled location services on their personal devices, up from 74% in 2013 (Anderson, 2016). Once enabled, social networking applications are granted access to a user’s geographic location and able to use this data to generate a folksonomy of content. Upgrades to latest versions of social networking platforms have shifted towards placing more importance on geotagging to help facilitate the way in which social media users experience the online world. They have also helped to foster a sense of community within an interactive Web 2.0 world, by supplementing physical space on social networking platforms, allowing users to create more meaningful content by utilising these location-based features. This may include checking-in on Facebook, adding a location to a photograph on Instagram, or even using a geofilter on Snapchat. Geotagging and other location-based affordances of Web 2.0 social networking platforms create a physical spatial substitute, supporting the formation of group identities and practices of online communities.

This paper will initially look at the proliferation of Web 2.0 online communities, as well as the advent of the smartphone and integration of location-based services and how this has led to a shift in user behaviour towards location-based social networking. I then look at the examples of SnapMap on Snapchat, Facebook Marketplace and Pokémon GO, and how they have integrated geotagging and other location-based affordances to foster a sense of belonging and nurture interaction within these online communities.

Web 2.0 Online Communities

Similar in manner to Baudelaire’s concept of the flâneur (Baudelaire, 2010), user behaviour on the internet originated with individuals surfing various web pages to access and consume information in a sense as mostly a detached observer. This “cyberflâneur” as depicted by Goldate (1998) was initially theorised as a figure who was able to browse various online offerings without the need to contribute or interact. However, Web 2.0 was born out of a need for users to have increasingly autonomous and dynamic online experiences, and with this, a prevalence of communities began to surface and proliferate. Just as Benedict Anderson (1983) in Imagined Communities argued that print capitalism and an increase in access to resources written in the vernacular allowed imagined communities to form and feel a sense of belonging, so too were the formation of online communities on various Web 2.0 social networking platforms. The convergence of technology and asynchronous platforms that facilitate communication have allowed users a more interactive and meaningful online experience. They are now able to easily share content and broadcast their interests/ideas/musings, subsequently interacting and facilitating discussion with like-minded individuals.

Significantly, Aguiton and Cardon (2007) determined that individuals built their self-identity through the ‘continuous search for recognition in the eyes of others,’ and online communities (in place of Anderson’s imagined communities) were the platforms with which to facilitate this emergence of common discourses. Constant upgrades are made to social networking platforms, moving towards a more seamless integration of the online and offline world, with developments often reflective of user behaviour and trends. One such upgrade has been the shift towards incorporating location-based affordances that nurture interaction within online communities.

The Advent of the Smartphone & Location-Based Social Networking

The proliferation of personal devices, particularly the advent of the smartphone, was the catalyst towards a new form of location-based social networking. In early 2013, Facebook made an adjustment to its Application Programming Interface (API), which provided users with the option to enable location-sharing across third party applications (Wilken, 2014). This simplified the way users were able to include their location into a social media update or interaction, and soon, this became the norm in their online behaviour. Another Facebook upgrade in the early 2010s was the ability to incorporate hashtags, or personal tagging, which too became normalised social media behaviour and allowed users to tag, and thus categorise, their content. Users were also able to incorporate geotagging, which Kapko (2014) argues was a way to make mundane longitudes and latitudes meaningful when placed in context with various social media interactions. This convergence of location-based sharing and content tagging normalised user behaviour of creating content that incorporated location as a representation of physical space.

Online communities were also better able to integrate this location-based behaviour in their interactions with others. When users are geographically distanced, the real-time sharing of user location allows online communities to strengthen their sense of rapport as individuals are unified through their provision of their location. The online representation of their physical place in the offline world is a pivotal and personal component of user identity that other members of the community may identify with through their understanding of that physical place. Gruzd (2011) endorses this, in that users need to imagine that they – or others – belong to a community, and this includes the provision of that physical spatial substitute, through the sharing of their location. As with Anderson’s imagined communities, so too can online communities utilising social networking platforms forge a sense of belonging through their commonalities.

The Importance of Location on Snapchat

A social networking platform that is heavily reliant on integrating this location-based online behaviour is Snapchat. Launched in 2011, the social networking platform is comparatively different to alternative social networking platforms. Social networking sites (SNS) have been typically defined by Elison and Boyd (2007) as web-based services that allow individuals to create a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system. Snapchat differs in that it is a smartphone-based application where users are able to share content (privately, or publicly via their stories) in place of a profile, and is only accessible to viewers for a limited time period. Users are unable to leave a long-term record of the content they have generated or a digital footprint, characteristic of other SNS’. Additionally, Kapko (2016) has found that Snapchat elevates the importance of location-based social networking and places it at the forefront of the user experience on the platform. The locations where interactions take place increasingly become an integral part of the social media dialogue (Bernabo-Moreno et al., 2018). This is particularly pertinent for Snapchat, where content is shared sporadically and spontaneously, therefore the inclusion of location supplements that content. Bernabo-Moreno et al. (2018) also believe that geotagging used in this context places further significance and emotional impact on an event, based on the social media user-generated content attached to a location.

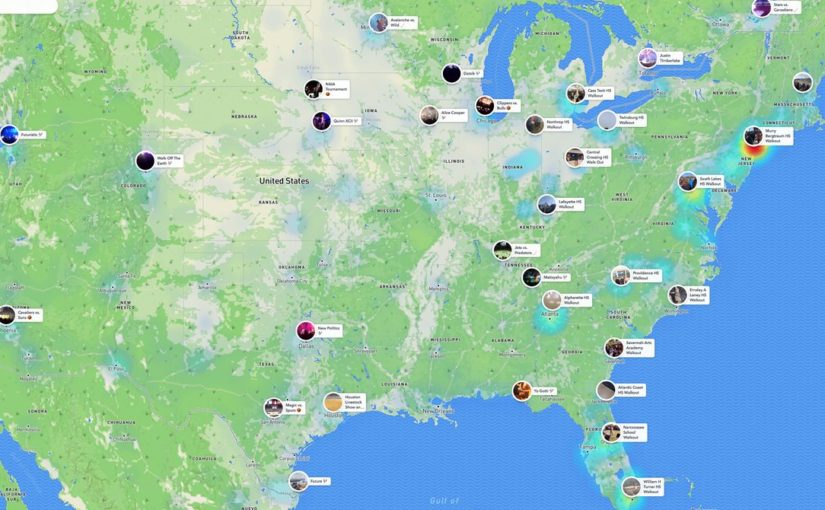

Furthermore, an upgrade to Snapchat in 2017 introduced Snap Map, a new feature which allowed users to share their location (and subsequent content) in real-time on a world map available for those that had this feature enabled to view, intending to assist users and facilitate engagement in the offline world. On March 14 2018, Snap Map went viral due to the merging of its functionality with online community engagement when the map was used as a way for high school students to protest school shootings, uniting as a community through the provision of their location online. By marking their place on the Snap Map, they were displaying their stance on opposing gun violence (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). The location-based geotagging as an online representation of their physical location on Snapchat thus provided this online community with a way to form a strong sense of unity and belonging.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Online Communities & Facebook Marketplace

The introduction of the Facebook Marketplace is another example of a Web 2.0 platform that has utilised location-based social networking as a way to facilitate local community engagement. Introduced in 2016, the feature is a hub for users to sell, trade and barter in the same sense as they would in a traditional marketplace in the offline world. Anyone with a Facebook account is able to list various items online, similar in a sense to classified advertisements, and these are listed for other users based on their proximity to the seller. If a user has shared their location and is within close proximity to the seller, their item is likely to be listed higher and individuals can then facilitate a conversation to discuss the transaction further, or exchange an item for a fee. This type of private trading initially began within various Facebook groups, with local communities who were already connected with one another able to facilitate these forms of exchanges (Ku, 2016). By incorporating the figurative traditional marketplace with Facebook’s location-based functionality, this feature may also be interpreted as an extension of offline local communities, as represented online. As with the Snap Map feature on Snapchat, it may also be regarded as first and foremost a proponent that helps to leverage the facilitation of real-time engagement. Kellerman (2016) argues that the only communication medium that rivals the ‘topological flexibility of computer networks’ is place itself, placing precedence on interaction within the real world. Yet these forms of socio-spatial online formations allow verified users to safely interact with others online, before facilitating offline engagement, and continue to strengthen their sense of community. Therefore, it remains pivotal for such developments and upgrades to social networking platforms to continue to prioritise the offline world.

Pokémon GO & the Implications of Location Sharing

Despite the benefits location-based social networking platforms have provided for the formation and sense of belonging within online communities, it is important to consider the implications that may occur as a result of sharing this personal information. There have been privacy concerns raised due to users openly sharing their location and the normality that has been placed on this form of interaction. One such example of this is when the augmented reality game Pokémon GO, was launched in 2016. Pokémon GO incorporates geospatial mapping as part of the gameplay and relies heavily on players sharing their location to progress in the game and proceed throughout the different stages. Players of the game were able to participate in Community Days, where they were able to meet with other players within their local community, as determined by their location-enabled devices, to play a ‘bonus game,’ and for a limited time period, partake in an entirely new experience of the game. The rapid success of the game meant that multitudes of players were knowingly trespassing into private property and causing nuisance in order to progress in the game, with disregard for those that owned or maintained the property (Shum, 2017). As Arora (2014) argues, users exercise cognitive mapping strategies to navigate their virtual environment in the same manner in which they approach real spaces. Although these location-based affordances allow users to integrate the offline and online world, they are not a form of permission to trespass or interfere with private property, just as sharing location on another social networking platform does not provide permission for users to trespass into that offline location. It is this boundary between the two worlds that needs to be closely examined even more so as our personal devices continually upgrade to include new functionality that integrates our location in the offline world with our interactions and behaviours online.

Conclusion

As Web 2.0 social networking platforms continue to develop, we will continually witness advancements in the integration of location-based functionality. As Arora (2017) argues, space has become even more important in reconfiguring and expanding our notions of social practice, both online and offline. No longer will the cyberflâneur web surfer simply be riding the online virtual waves, but will instead be actively seeking out dynamic and interactive rich-content in their experience and interaction online. As geotagging and location-based affordances continue to take their pivotal place in the Web 2.0 online experience, meaningful location functionality should be considered so as to help foster the sense of belonging that takes place within online communities. Users must also remain conscious of their behaviour online as they share their current location using their personal devices and consider the implications doing so may have in terms of privacy and data-sharing. Arora (2014) deems the digital realm as intimate, yet distant. The physical spatial substitute that location-based services provide will continue to allow users to feel a sense of belonging and support the formation of group identities. It will also allow them to continue to have meaningful interactions within their online communities. Web 2.0 will continue to prioritise the autonomous online experience of users and thus feel they are able to share content, including the provision of location via these location-based services. Future imaginings of how this will continue to shift are endless, particularly as technology moves towards the proliferation of wearable devices, as well as facial and fingerprint recognition on our smartphones. Location continues to have an important part in the way we experience the ever-changing technological landscape; as Wilken (2014) surmises, ‘life happens in real time and so should sharing’.

References

Aguiton, C., & Cardon, D. (2007). The Strength of Weak Cooperation: An Attempt to Understand the Meaning of Web 2.0. Communications & Strategies, 65(1). Retrieved from:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1009070

Alter, C. (2018, March 14). Student walkouts are basically the only events showing up on Snapchat Map right now #nationalschoolwalkoutday [Tweet]. Retrieved from:

https://twitter.com/CharlotteAlter/status/973974952994013184

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities. Reflection on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Anderson, M. (2016, January 29). More Americans using smartphones for getting directions, streaming TV. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from:

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/29/us-smartphone-use/

Arora, P. (2014). Metaphor as Method: Conceptualizing the Internet through Spatial Metaphors. In The Leisure Commons, A Spatial History of Web 2.0. London: Routledge. (pp. 33-51). Retrieved from:

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=1721046&ppg=33&query=

Baudelaire, C. (2010). The Painter of Modern Life. London: Penguin Books.

Bernabé-Moreno, J, Tejeda-Lorente, A. Porcel, C. Fujita, H. Herrera-Viedma, E. (2018). Quantifying the emotional impact of events on locations with social media. Knowledge-Based Systems, 146, 44-57.

https://doi-org.dbgw.lis.curtin.edu.au/10.1016/j.knosys.2018.01.029

Elison, N.B and Boyd, D. (2013). Sociality through Social Network Sites. In W.H Dutton (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies (pp. 151-172). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fendi, K., Adam, S., Kokkas, N. and Smith, M. (2014). An Approach to Produce a GIS Database for Road Surface Monitoring. APCBEE Procedia, 9, 235-240.

Goldate, S. (1998, May 19). The Cyberflâneur – Space and Places on the Internet. Ceramics Today. Retrieved from:

http://www.ceramicstoday.com/articles/051998.htm

Gruzd, A. Wellman, B. and Takhteyev, Y. (2011). Imagining Twitter as an Imagined Community. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(10), 1294 – 1318. Retrieved from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0002764211409378

Kapko, M. (2016, April 28). How Snapchat paves the way for future of location marketing. CIO. Retrieved from: https://www.cio.com/article/3062600/marketing/how-snapchat-paves-the-way-for-future-of-location-marketing.html

Kellerman, A. (2016). The Internet as Space. In Geographic Interpretations of the Internet (pp. 21-33). Retrieved from:

https://link-springer-com.dbgw.lis.curtin.edu.au/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-33804-0

Ku, M. (2016, October 3). Introducing Marketplace: Buy and Sell With Your Local Community. Facebook Newsroom. Retrieved from:

https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2016/10/introducing-marketplace-buy-and-sell-with-your-local-community/

Morrison, T. (2018, March 14). Incredible moment on social media — East coast schools are walking out, calling on Congress to act on gun violence. @Snapchat’s @SnapMap feature visualising this movement in the most amazing way… [Tweet]. Retrieved from:

https://twitter.com/THETonyMorrison/status/973937933353934849

Shum, A., Tranter, K. (2017). Seeing, Moving, Catching, Accumulating: Pokémon GO and the Legal Subject. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law. 30(3), 477-493. Retrieved from:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11196-017-9519-8

Wilken, R. (2014). Places nearby: Facebook as a location-based social media platform. New Media & Society. 16(7), 1087-1103. Retrieved from:

http://journals.sagepub.com.dbgw.lis.curtin.edu.au/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444814543997

Download Conference Paper as PDF

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.