Abstract

Social media has changed feminist communication and activism strategies from small, local movements to vast, global campaigns. The use of filters on social media has allowed communities of strangers to form so they may carry out global and multilingual feminist campaigns. The use of social media by such campaigns has the added effect of empowering young women and girls while giving them online safe spaces to practice speaking out.

Introduction

The widespread adoption of social media has changed the way young women and girls participate in communities and develop their identity through experimentation. In this paper I will argue that the collaborative nature of social media has accelerated feminist movements among young women and girls. The emergence of ‘call-out culture’ on social media platforms –Twitter in particular – has shown girls that it is acceptable to call out misogyny (either external or internal) as they no longer have to strive for male acceptance. The days of girls proudly announcing that they are “not like the other girls,” seem to have come to an end, no longer making femininity something to be ashamed of. The #MeToo movement on Twitter has emboldened women and girls across the world as the platform has provided a public space for women to discuss their bodily autonomy and that misbehaviour will no longer be accepted with a cringe or a shy smile.

History of feminist communication

When it comes to feminist communities through the ages I will be describing the history of feminism in the United States of America (USA) as the majority of English speaking internet users are based in the USA (Internet world stats, 2019).

Early American feminism began in the 1840s (National Parks Service, 2015) with discussion and demonstration by women who wished for the right to vote. The methods of communication were public speeches and demonstrations, what was considered ‘un-ladylike’ behaviour at the time. The feminist community was limited to one group of white, cis-gendered, middle-class women who would have to meet in person, so numbers were limited based on location. Despite low numbers and geographic limitations this movement was able to achieve the right to vote for women in the USA by 1920 (National Archives USA, 2019).

In the 1960s the message changed from the struggle of women as a ‘class’ to become about individual rights or “identity politics”. The demonstrations began at a 1968 Miss America event comparing them to cattle displays (Gay, 2018). The communication strategy of this ‘second wave’ of feminism was demonstrated through mock beauty pageants where a sheep was crowned Miss America and by discarding – sometimes burning – objects seen as symbols of patriarchal control over women. The style of demonstration was mostly by protest marches and sit-ins (Jackson, 2018) and news of these demonstrations were reported in national newspapers (Gay, 2018). This wave of feminism was seen as quite radical with some members of the movement stating that they hated men and women are superior to men – essentially becoming the very thing they were fighting against. These women lead to the caricature of the feminist who is a “man-hating, lesbian, with bad hair”. The notion of female superiority could also explain the ingrained hatred of the word feminism by some men even today (Rúdólfsdóttir & Jolliffe, 2008), particularly ‘trolls’ who attack female activists online.

In the 90s feminism changed slightly from the second wave with how it was presented. The lipstick feminist (Jackson, 2018) was born, where the feminists of the 60s refused to wear bras, high heels or other restrictive clothing that they considered created by men, 90s feminists wore excessively feminist clothing and bright lipstick as if to reclaim femininity for women. This wave continued reclamation of their identity from men by appropriating the use of words like “slut” or “bitch” to take power away from such insults in a similar way to how African Americans use the “n-word” (Rahman, 2011).

Call out culture has emboldened a generation of women

Call out culture – a culture of publicly calling out inappropriate behaviour – has become the norm on social media (H., 2017). This has changed how young women develop their identities as, on social media, there is no expectation for women to simply accept poor behaviour from men. In the physical world there is the fear of physical violence if a man is challenged for offensive behaviour, but online the assumption is that the worst to come would be a nasty comment back. Young women are learning through social media that they do not have to tolerate offensive comments and seem to be bringing this lesson to the real world.

Social media can be seen as a ‘safe’ space for young women to discuss feminism as they are able to participate in communities with likeminded users. There is always the risk of trolls infiltrating a group but call-out culture has lessened the effect of their toxic comments. The majority of women who participate on social media have received toxic comments, many with threats of bodily harm or rape. These toxic comments showcase how threatening it is for some men to encounter women who are willing to speak their minds and break from the status quo demonstrating the dramatic change that social media has enabled.

Digital feminism

The global adoption of social media gave rise to digital feminism, sometimes referred to as ‘fourth wave feminism’ (Gay, 2018), where most – if not all – of the activism and discourse occurs online. Campaigns can spread rapidly all over the globe through social media as information can be shared with thousands of followers with one post.

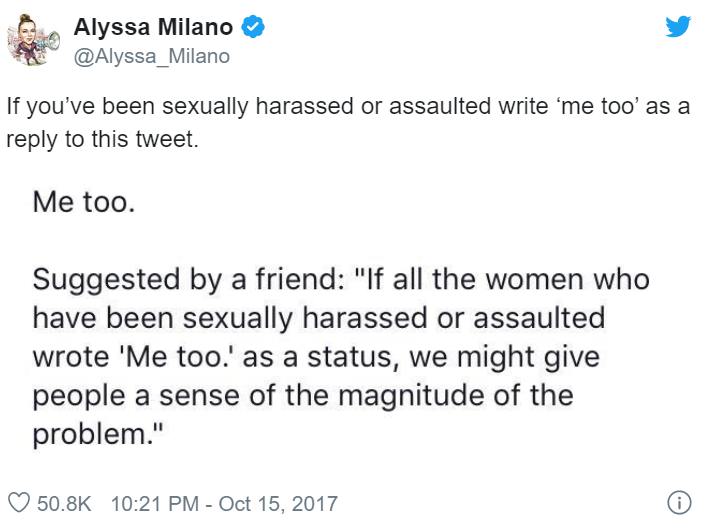

One notable campaign was the #MeToo movement on Twitter (Denomme, 2019). “Me Too” was a phrase coined by activist Tarana Burke in 2006 (Garcia, 2017) as part of a campaign to provide survivors of sexual assault support. In 2017 actress Alyssa Milano Tweeted, “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet” to show the extent of sexual harassment in society.

The actress made the tweet in reaction to a public accusation of a well-known movie producer of sexually assaulting numerous women throughout his career. Within one day the post was followed by 500,000 tweets (Respers France, 2017) and 4.7 million Facebook posts (Santiago & Criss, 2017) were made with the hashtag.

Since the original post there have been versions in other languages – #BalanceTonPorc, #YoTambien, #QuellaVoltaChe, #RiceBunny (米兔)(Caro, 2017) – showing the reach of social media beyond the limitations of language. This mass translation has formed separate campaigns within each country that has shared similar stories to the English speaking movement.

Online communities, public discussions

Children raised during the 90s were taught to be wary of strangers on the internet, not to share identifying information and not to meet them in person. Now we use the internet to have in-depth discussions with strangers and even use apps to meet strangers so that we can get in their cars so they can take us to a second location – also strongly advised against in the 90s. Social media has changed how we view strangers, it has allowed people to find people with similar interests regardless of how obscure so we can make friends without ever meeting them in person (Gruzd, Wellman, & Takhteyev, 2011).

Social media platforms use tags to organise discussions, Twitter uses hashtags – denoted by the symbol ‘#’ – so users can search a hashtag to join discussions with like-minded strangers. These tags allow users to join any public discussion and make friends to have private conversations with later. Tags allow users to customise their consumption of information on social media platforms – where a lot of people get their news (David, 2019). Tags also allow the platform to make suggestions for other tags or users to engage with that they may like. This can lead to people developing a form of tunnel vision of world events as their primary source of news has been filtered to suit their world view.

Social media platforms have allowed feminist discussions and campaign organisation to occur without needing to consider physical barriers (Martin & Valenti, 2012). They can take the form of public threads on Twitter, semi-public forums on Reddit or even in private groups created on Facebook. Women and girls are also able to remain relatively anonymous so they do not feel self-conscious of how they look or sound when making comments online. Due to the personas created for social media, the platforms provide a safe space for younger women and girls to take part in discussions and express themselves freely (Stern, 1999).

Public collaborations – such as the #MeToo movement on Twitter – have brought young women and girls to the feminist movement. Women shared so many stories of their struggle in a sexist world that every woman and girl was able to find a story they could relate to or sympathise with. This gave the feminist movement cohesiveness as women and girls were seeing that they are a group with similar experiences from across the world.

Women and social media.

Young people (18-24) are the most prolific users of social media and women are more likely to use social media than men (Pew Research Centre, 2017). The number of women using social media platforms is constantly increasing even in countries where women are less likely to have a public voice (Martin & Valenti, 2012) providing some with a space with more freedom than in their own country. Social media enlarges the recruitment base for feminists by doing away with physical barriers like distance and isolation as well as language barriers as more platforms automatically translate posts (Facebook, 2020).

Social media platforms are a place where young women can learn and be empowered through discussion as well as through recognition that is quantified by ‘likes’ and ‘shares’ of a post. This model of public statements with instantaneous reactions has allowed young women to develop their identity in a safe space and rapidly experiment with communities without needing to leave their bedrooms (Boyd, 2007). This is particularly empowering for young women in societies that are not very nurturing towards women who wish to develop their identity as it is harder for the morality police to find someone with a fake social media account (Agarwal, Lim, & and Wigand, 2011).

While social media can provide safe places where anything can be discussed at length it is still not safe from attack. A lot of women (young women in particular) are wary of making a post about feminism on a public forum because of the risk of attracting misogynistic trolls (Jackson, 2018). Some trolls will also engage in coordinated attacks on activists – or game creators as was the case in the notable “Gamergate” campaign (Ryan Vickery & Everbach, 2018) – meaning women could risk becoming a target both on and offline if they make a post deemed too controversial.

Privacy through obscurity

Teenage girls will often use social media platforms as their main method of communicating with friends they know in real life through group chats or pages. These private groups are where discussions with people who have the same interests and come from similar socioeconomic backgrounds can take place. Due to the specific conversation topics and assumed participants there is an expected level of privacy even though the conversation is taking place in on a public space. Some girls will use pseudonyms and removing all identifying information so that their parents are unable to monitor what they are discussing online (Boyd, 2007). Another method of protecting privacy among teens is to create two accounts: one with their real name and school; the second with fake names and information. Fake social media accounts – also called a finsta (Varma-White, 2017) – are another way for girls to navigate social media in privacy away from other social media users as a fake identity removes the risk of being harassed in real life by users offended by a feminist tweet.

Social media platforms allow users to filter their experience by choosing a list of topics they wish to see through tags. This has provided some groups’ a perceived privacy through obscurity as you would need to know the name of the group or tag to engage in their discussion. If the group remains small enough it will not attract attention from the general pool of platform users and can exist in a public space with a level of privacy through obscurity (Russel, 2015). The general fear of misogynistic attack online that women have can be abated when there are small feminist communities that are able to thrive. Women are able to refer each other to these groups and feel free to discuss feminist issues without agonising over each word in their comments online.

Conclusion

Feminism over the last century has been a constantly changing movement, but social media has launched the movement to the mainstream. Female celebrities – once seen simply as decoration – are now at the forefront of campaigns like the #MeToo movement. Digital feminism has allowed movements and campaigns to move at breakneck speed and give the movement strength in numbers in many different countries at once. The public nature of social media has provided young women a space to join public discussion as well as experiment with different communities in a safe space. While there are risks of engaging in public discourse there are ways that young women are protecting themselves from online trolls – and their snooping parents – further allowing young women to develop their online identities with complete freedom to choose their life story. Misogynist users on social media have also served as a useful tool for young women as they are learning to call-out poor behaviour rather than simply tolerating it and hoping they will go away. The collaborative nature of social media has accelerated feminist movements among young women and girls and given them a safe space to form communities for support and empowerment.

References

Agarwal, N., Lim, M., & Wigand, R. T. (2011, June). Finding her master’s voice: the power of collective action among female muslim bloggers. In ECIS (p. 74).

Boyd, D. (2008). Why youth (heart) social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life. YOUTH, IDENTITY, AND DIGITAL MEDIA, David Buckingham, ed., The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2007-16.

Caro, B. D. (2017, October 18). #MeToo, #balancetonporc, #yotambien: women around the world fight back at harassment. Retrieved from World Economic Forum: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/10/metoo-balancetonporc-yotambien-women-around-the-world-lash-out-at-harassment/

David, C. C., San Pascual, M. R. S., & Torres, M. E. S. (2019). Reliance on Facebook for news and its influence on political engagement. PloS one, 14(3).

Denomme, A. M. (2019). From Viral Hashtag to Social Movement: The Rhetoric and Realization of# Metoo (Doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia).

Facebook. (2020). News Feed Translations. Retrieved from Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/help/763911877050983

Garcia, S. E. (2017, October 20). The Woman Who Created #MeToo Long Before Hashtags. Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/20/us/me-too-movement-tarana-burke.html

Gay, R. (2018, January). Fifty Years Ago, Protesters Took on the Miss America Pageant and Electrified the Feminist Movement. Retrieved from Smithsonian Magazine: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fifty-years-ago-protestors-took-on-miss-america-pageant-electrified-feminist-movement-180967504/

Gleason, B. (2018). Adolescents becoming feminist on Twitter: new literacies practices, commitments, and identity work. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62(3), 281-289.

Gruzd, A., Wellman, B., & Takhteyev, Y. (2011). Imagining Twitter as an imagined community. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(10), 1294-1318.

H., R. (2017, May 2). Call-Out Culture Isn’t Toxic. You are. Retrieved from Medium: Katelyn Burns

Internet world stats. (2019, June 30). Top 20 Countries with the Highest Number of Internet Users. Retrieved from Internet World Stats: https://www.internetworldstats.com/top20.htm

Jackson, S. (2018). Young feminists, feminism and digital media. Feminism & Psychology, 28(1), 32-49.

Martin, C. E., & Valenti, V. (2012). #FemFuture: Online Revolution. New York, USA: Barnard Center for Research on Women.

National Archives USA. (2019, May 16). The 19th Amendment. Retrieved from National Archives Museum: https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/amendment-19

National Parks Service. (2015, February 26). Report of the Woman’s Rights Convention. Retrieved from National Historical Park New York: https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/report-of-the-womans-rights-convention.htm

Pew Research Centre. ( 2017, January 11). Social media use by gender. Retrieved from Pew Research: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/chart/social-media-use-by-gender/

Rahman, J. (2012). The N word: Its history and use in the African American community. Journal of English Linguistics, 40(2), 137-171.

Respers France, L. (2017, October 16). #MeToo: Social media flooded with personal stories of assault. Retrieved from CNN: https://edition.cnn.com/2017/10/15/entertainment/me-too-twitter-alyssa-milano/index.html

Rúdólfsdóttir, A. G., & Jolliffe, R. (2008). I don’t think people really talk about it that much’: Young women discuss feminism. Feminism & Psychology, 18(2), 268-274.

Russel, N. (2015, September 21). Of Social Media Privacy Through Obscurity. Retrieved from Slaw: http://www.slaw.ca/2015/09/21/of-social-media-privacy-through-obscurity/

Everbach, T., & Vickery, J. R. (2018). Mediating Misogyny: Gender, Technology, and Harassment. Taylor & Francis Limited.

Santiago, C., & Criss, D. (2017, October 17). An activist, a little girl and the heartbreaking origin of ‘Me too’. Retrieved from CNN: https://edition.cnn.com/2017/10/17/us/me-too-tarana-burke-origin-trnd/index.html

Schuster, J. (2013). Invisible feminists? Social media and young women’s political participation. Political Science, 65(1), 8-24.

Stern, S. R. (1999). Adolescent girls’ expression on web home pages: Spirited, sombre and self-conscious sites. Convergence, 5(4), 22-41.

9 replies on “Communities without borders: Feminism fuelled by social media”

Hi Stephanie,

Love your title! It perfectly expresses what you’re trying to say.

I enjoyed your analysis of social media activism. I definitely related to the topic – being an avid Tumblr user in my high school years, my school laptop has a Feminist sticker proudly displayed on it.

Your introduction was a good, succinct background of feminist history. I also liked that you were able to identify the original post for #MeToo, as well as talk about how female celebrities are speaking up more.

I also would have loved to hear more about Gamergate to refresh my memory. It would have been good if you could have expanded further on how trolls attack women exactly, just to clarify the dangers of digital media. I know word counts are a thing and it’s good to see you did mention a study!

I do feel like being a “feminist” is also something some females don’t like to be labelled as – I have overheard females rejecting the label in front of males. Is this something you came across in your research?

Great work!

Anne-Marie

Hi Anne Marie, thank you very much for your comment. I have indeed come across some research indicating that women/girls reject the title of feminist in front of men/boys – I can recommend the journal article The “F” Word: How the Media Frame Feminism by Debra Baker Beck as she outlines the effect media portrayals of feminists has on consumers.

As for Gamergate I would love to refresh your memory as I am hoping the comment section has no word limit! #Gamergate is a controversy that was supposed to be about journalistic integrity but devolved into the attack on a female game creator – Zoe Quinn – who had supposedly cheated on her blogger ex-boyfriend with gaming journalists so they would promote her text-based game. This was not a simple attack on social media, it was a coordinated campaign on several platforms. Quinn was stalked on social media and in real life as her address and phone number were posted online so that “activists” could threaten her in person or leave abusive voicemails. It is an example of the dangers women have to consider when posting online. The treatment of Quinn is a warning to women online that they can find themselves in real danger at any time. There wasn’t actually any proof that Quinn cheated on her ex-boyfriend with gaming journalists and even if it were true, threats of sexual and bodily harm from strangers are completely out of proportion to the “crime” of infidelity.

Hi Stephanie,

Interesting paper. As a woman in my early twenties I can definitely credit the internet for my knowledge of feminist issues and the fact I proudly identify as a feminist. Before I really started using the internet and social media I disregarded feminism as something we didn’t need anymore and thought the the term “feminist” unnecessary, even though I saw problems unique to women and thought equal rights were important.

I’m curious whether social media has anything to do with an almost shallow sort of feminism I see a lot online. For example, things such as the wage-gap being explained incorrectly.. Personally, I think it could be because the internet is such a fast-moving and information heavy place, that things often have to be short and simple or as out there as possible to get noticed. So people might not have time to get into explanations of the wage-gap when making a Tweet or writing a short article. Or it might be that feminism is gaining traction and a lot of people might not have had the time to look into it properly? But, I’m curious if you came across anything about this sort of thing in your research.

Kind regards,

Chloe

Hi Chloe, thanks for your comment. I am a little older than you but had a similar experience of considering feminism unnecessary when I was younger – I mean we had the vote and the right to work, what more do we even need?

I agree with your comment that social media has created a filter of misinformation as there is a need to stand out – recognising only outlandish statements with little factual backing. Short-form blogging platforms like Twitter has forced messages into soundbites which can then go on to be misinterpreted by people who will share these messages without fully understanding the statement. Your example of the wage-gap is good because it is an issue with so many facets beyond what people find in their pay-packet – the problem is that you can’t explain them all in even 4 tweets so it continues to be misunderstood on many sides.

Hi Stephanie, great paper, really powerful stuff. I’m familiar with most of the terms you’ve used but obviously as a man I haven’t experience them personally, though I have plenty of friends and family who have. It’s interesting how you begin by noting your research primarily deals with American statistics, I haven’t seen that in other papers so I wonder how true it is when people say America thinks they are the world, either way very responsible of you to note this; especially later when you note how #MeToo has expanded into other languages. These days when you hear about appropriate it seems to always be a bad thing, so I thought it was great to learn about how appropriation began as a way to reclaim power and how feminism has changed. In my own research I found communities welcome diversity as they bring in new ideas, and without diversity they grow stagnant and form bubbles or echo chambers, how do you think these online communities, these safe spaces to discuss difficult topics without toxicity stay safe while bringing in diversity? Are even they able to? Cheers.

Hi James,

Thanks for your comment. As a woman of mixed race, who grew up in various multicultural cities, I considered diversity to be the norm. When I moved to Australia and started at an Anglican school, I started to see homogeneous groups forming within my year and then I understood how tribal humans can be as all of the groups were based on race or where they lived.

I think you are right that communities that do not invite diversity become stagnant but I would go one step further to say that they can become dangerous echo chambers where opinions are repeated so often by the group that at some point they become accepted as fact. The thing I really like about online communities is the ability to essentially be anonymous, which in itself invites a level of diversity. The danger of this anonymity is that anyone with malicious intent can join these safe spaces who welcome diversity and bring in toxicity – either for fun or just plain hatred. The only way I have seen to avoid this is through constant moderation of these spaces, unfortunately once a space gets popular moderation becomes almost impossible unless you hire someone (or even a team) to moderate full time. Attitudes are also changing, many internet users are aware that ‘trolls’ are usually behaving in a toxic manner to get a reaction so they know to ignore them – “Don’t feed the trolls,” being a common saying in forum rules. So I think they are able to stay safe spaces, but only to a certain extent, and they are getting safer through moderation and changing attitudes online.

Thanks,

Stephanie Cheng

Hi Stephanie,

This was a great paper and very enjoyable to read.

Here are some of my thoughts/questions –

1. “The methods of communication were public speeches and demonstrations, what was considered ‘un-ladylike’ behaviour at the time.”

– I really loved learning more about the history of feminism – it really blows my mind to know that not too long ago women speaking up was considered “un-ladylike’.

2. “The demonstrations began at a 1968 Miss America event comparing them to cattle displays (Gay, 2018). The communication strategy of this ‘second wave’ of feminism was demonstrated through mock beauty pageants where a sheep was crowned Miss America and by discarding – sometimes burning – objects seen as symbols of patriarchal control over women.”

– This is so crazy – I can’t believe I didn’t know this happened. Was it a movement creating by women to show the way men were treating them? Or was the event held by men to mock the women?

3. “The lipstick feminist (Jackson, 2018) was born, where the feminists of the 60s refused to wear bras, high heels or other restrictive clothing that they considered created by men, 90s feminists wore excessively feminist clothing and bright lipstick as if to reclaim femininity for women”

– As someone who loves and has studied fashion (have a look at my paper if you’re interested as my topic was based on fashion), this is so interesting to me. I didn’t know that 90’s fashion choices were due to feminism. I love that! 90s fashion has always been a favourite era of mine.

4. “This wave continued reclamation of their identity from men by appropriating the use of words like “slut” or “bitch” to take power away from such insults in a similar way to how African Americans use the “n-word” (Rahman, 2011).”

– This is also anther very interesting point and sad that words like these still get thrown around today, especially on social media as you explain in the following paragraphs.

5. “Young women are learning through social media that they do not have to tolerate offensive comments and seem to be bringing this lesson to the real world.”

– I’ve definitely noticed this too – I feel like when social media first came about, people were quick to send hate as they felt comfortable hiding behind their screen and keyboard. However in the recent years, I have definitely seen a shift (especially in women), where most will not tolerate offensive comments (either by blocking them, responding back themselves or comments by others who stand up for the person being posted about) which is great.

6. “Social media can be seen as a ‘safe’ space for young women to discuss feminism as they are able to participate in communities with likeminded users.”

– Which online communities are you referring to here? Are you apart of any? I’ve been loving following Abbie Chatfield and am a part of her podcast Facebook group which is filled with so many amazing, uplifting women who support each other.

7. “Within one day the post was followed by 500,000 tweets (Respers France, 2017) and 4.7 million Facebook posts (Santiago & Criss, 2017) were made with the hashtag.”

– Wow, and this is why I love the power of social media. Amazing!

8. “Fake social media accounts – also called a finsta (Varma-White, 2017) – are another way for girls to navigate social media in privacy away from other social media users as a fake identity removes the risk of being harassed in real life by users offended by a feminist tweet.”

– I find this quite sad that girls feel the need to create fake accounts to be able to feel safe in expressing their true selves. But at the same time, I can completely sympathise with this choice as I can see how doing this would provide a level of anonymity and security.

After reading your paper, I agree that whilst there are some negatives for feminist activists online (like dealing with online trolls and misogyny etc), I do think that overall social media is a positive platform for feminists in bringing movements like #MeToo to life and also not letting trolls get away with bad behaviour.

Emily

Hi Emily,

Thank you very much for your detailed comment, I really appreciate how you thoroughly read my paper.

I agree that it is sad how many women feel the need to essentially hide behind false identities to safely engage in social media, but it also gives me hope that young women and girls can use them to develop the confidence to fight back against aggressive users. There have always been negatives when any group tries to change the status quo, it is just easier to track around digital movements because everything is recorded and generally accessible to the public when posted online. I feel the negatives are outweighed by the accessibility afforded by online platforms as even in China (where access is censored) international movements are penetrating the population, giving strength to campaigns that has never existed before.

To answer your questions:

– 2. The event was hosted by the women protesting the Miss America Pageant. A sheep was rented from a farm to draw attention to how the real contestants were treated like cattle in a meat market. They were (are?) ordered to look, walk and act in the same way to win a competition that would lead to roles where they were essentially treated as decoration. I have found a first hand account of the event here if you would like to read more about it.

– 6. There are many small online communities on various popular social media platforms, they tend to stay small and private to avoid troll group attacks as those are still very common. I myself am a member of some private Facebook groups that have feminist discussions online and in person in Sydney. I am also an active user in some feminist leaning ‘subreddits’ on Reddit – a platform mostly known for male-centred discussion – where I can have discussions about women’s issues (mostly in a satirical way) with women all over the English speaking world.

Thanks again for your comment and I will make sure to read your paper!

Stephanie

Hi Stephanie,

That is very true that there are always negatives if someone tries to change the status quo – even if there are positives to changing it in the first place. Ah yes the Chinese censorship.. it’s such an intriguing thing.

2. Wow that’s very interesting. I will definitely have a further look into the event. Do you think this had a positive or negative outcome overall?

6. Yeah I can definitely understand that people would rather keep their communities more private but that’s so cool that you’re apart of an in person community in Sydney. How does that work? Do you have events etc?

Emily