Written by Callum Duffy, Curtin University

Abstract: This paper largely focuses on the relationship between Online Gaming and the various Communities formed because of it. Specifically analysing communities found by using ‘Overwatch’ as a prime example, the main argument presented is that various communities focused on a single, core aspect unifying them all are more or less interconnected individuals with similar general interests in regards to this core aspect, and thus have the potential for collaboration and dialogue between each other.

The relationship between communities and online gaming is, at its very core, a relationship that is symbiotic in nature. In relevance to this, this conference paper will focus primarily on the formation of communities in regards to online gaming, the variation of interests within formed communities and how these vary and diverge into different niche communities, the formation of friendships between members existing within the same community, and how these communities still relate to one another in regards to a singular, dynamic interest. For this conference paper, we will specifically be looking at the various communities that are brought together by the popular FPS game produced by Blizzard entertainment, ’Overwatch’.

A community, as defined by Gusfield (1975) focuses on two primary concepts when defining community, The first of these concepts focusing on the geographical sense of community, etc. neighbourhood, town, city. The second is relational, concerned with quality of character of human relationship, without reference to location (p. xvi). In regards to online gaming, the second definition of community provided by Gusfield is an accurate definition as to what an online gaming community is, as the relationships formed through online gaming isn’t limited by the boundaries of geographical location, as the online medium allows player to connect with each other and form relationships/communities with one another. In relation to this, Overwatch allows players from all over the world to play against one another as it isn’t limited by geographical restrictions, this allowing players to connect and as a result allowing the formations of communities, regardless of geographical location. Overwatch itself particular is a game with various communities that have been formed from it’s large, generalised community of those who play the game. I will focus on 3 different communities within the generalised player community, these being the casual, competitive and e-sport based Overwatch communities. It’s important to note that these 3 chosen communities do not accurately represent the different niche groups that exist with the generalised Overwatch player base community, rather, they represent the shift in community based priorities in relevance to Overwatch as a whole, and the interests that each group prioritises.

There are various communities within the game Overwatch that cater to the various players that play Overwatch. The casual Overwatch community represents the approximate majority of those who play Overwatch, and those involved within this community simply play the game for relaxation and enjoyment within their leisure time, and build friendships with the players that they meet in game, or through other communication mediums that allow members of this community to collaborate and share information. With this in mind, the primary methods of communication for those in this community are either the in-game voice chat, where individual players can speak to other players on their team, or Youtube comment sections, where they can leave comments under videos that appeal to them and their interests in relation to Overwatch. The ‘competitive’ Overwatch community focus primarily on the competitive game modes that Overwatch offers, where players get ranked based on their skill level. These players seek to improve their skills in playing a particular character, or acquire better game sense through more playtime and experience. More often than not, individuals that associate themselves with this community in particular diverge into different, niche communities that focus on the fundamental principles that the members of this community share. For example, if a player involved in the competitive community plays a particular character mores than others, he/she may also be involved in a sub-community that focuses on playing that particular character, certain exploits that players can use to better play that character, or a generalised appreciation community focusing on that character. The competitive Overwatch community uses a variety of ways to communicate, including the aforementioned methods that the casual community uses to communicate with. However, a difference in the communication side to this community in particular focuses on the application of the official Overwatch forums. These forums allow players to commentate on the state of the game overall, communicate with game developers and ask/answer questions, and communicate with like-minded players on specified topics. Finally, Overwatch’s e-sports community focuses on the ‘professional’ side of play, with professional Overwatch players receiving sponsorships, business deals in the form of contracting to an e-sports team, and being a general figurehead/role model for all Overwatch players. This community represents a minority within the Overwatch community, as the majority of Overwatch players do not associate themselves with the professional side of the game.

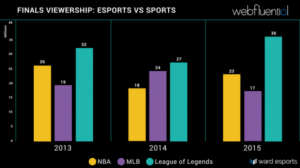

E-sports in particular, is arguably the most niche of communities that Overwatch offers. E-sports in itself is defined as “an area of sport activities in which people develop and train mental or physical abilities in the use of information and communication technologies” (Wagner, 2006). Individuals can be associated with E-sports as a competitor or more often than not, simply an observer. This is where the divergence of communities within the game Overwatch begin to reassemble into an amalgamate of individuals with similar interests. Namely, the aforementioned competitive community begins to shift towards a larger involvement in the e-sports community, be it as a spectator or an actual competitor. Overwatch itself has its very own e-sports tournament labelled ‘Overwatch League’, this league hosts various international teams, and has a central presence within the game itself. Overwatch allows player to purchase cosmetic items that represent these teams in game, in a fashion similar to that of a football jersey. With this in mind, this further strengthens the idea of merging different communities within Overwatch, as casual players have access to e-sports related cosmetics, and resources allowing them to further explore the professional Overwatch league.

The casual community found within Overwatch however, is the broadest of these communities that the vast majority of the player base fits into. Where casual players might play the competitive modes that Overwatch offers, they still see it as just a game, and don’t necessarily focus on the same aspects the the competitive communities of Overwatch may focus on. The formation of online friendships between individuals within this community are genuine and are capable to exist in an offline setting also. As said by Domahidi, Festl and Quandt (2014), “ Players with a pronounced motive to gain social capital and to play in a team had the highest probability to transform their social relations from online to offline context. We found that social online gamers are well integrated and use the game to spend time with old friends—and to recruit new ones”. With this in mind, the idea that communities are capable of bringing likeminded individuals together is solidified and proven. This is regardless of how niche a community may be, as for example, a casual player may be persuaded to become a part of a competitive community via friendships made online, or a simply change in opinion towards the game as a whole.

With the aforementioned in mind, the various communities that are found within Overwatch are capable of interacting with each other through various different means. Specifically mentioned before were the official Overwatch forums as a large medium used by those involved within the competitive Overwatch community. Youtube however, is the biggest way for the general Overwatch community members to gather information. Be it through the official PlayOverwatch account that posts official trailers, development updates and short animated films, or fan accounts that post game commentaries, professional game analysis or funny meme montages; Youtube is a medium that allows the vast majority of the generalised Overwatch community to interact with one another. Specifically, Youtube is a medium that connects well with younger audiences that have grown up in a digital era, specifically teenagers, which in itself can be considered a sub-community of Overwatch. Youtube content creators can be seen as social influencers that shape the foundation of the decision making process of their audiences, and there is no better example of this than the relationship between these social influencers and their teenage audience. As put by Chua & Banerjee (2015) “personal opinions and experiences have become one of the most valuable sources of information to assist users in their purchase decision-making process”. When the opinions of a professional Overwatch player is shared through Youtube, and reaches the screen of a fan of said influencer, there is a great chance that said fan will copy and follow the personal opinion and review of the influencer in question. Once again we see the merge between communities found within the general Overwatch community, in this case we see the casual, teenage audience form their own opinions and ideas on a particular idea based on the influence of a social influencer, more often than not in this case a competitive, celebrity figure that belongs to a niche community of Overwatch entertainers.

Thus, we are presented with a correlation between the various niche communities that belong to the generalised Overwatch community as a whole. This correlation is that the various niche communities influence one another, to the point where the divergence of these communities merge back together into a singular entity. This singular community is characterised and stereotyped to have specific traits shared amongst the members of this community, and with Overwatch in particular this generalised trait would be toxic gameplay that certain players bring to the table. This is recognised even by the developers of the game in question. In a video posted to the PlayOverwatch Youtube account, lead developer Jeff Kaplan addressed the audience about the increased negative social interactions that occur between player of the game, and the steps that the team are taking to rid toxicity from the game. In the video, Kaplan states, “We have taken disciplinary action against over 480,000 accounts, and 340,000 of those were a direct result of players using the reporting system. So you can see, the vast majority of actions we take are because players have said hey, there’s another player here doing something very bad and I want to see some action” (PlayOverwatch, 2017). In regards to this video, we can see that the Overwatch community are characterised by being toxic in game. However, we can also see that this is a big problem that many individuals both inside and outside of this community want to see be dealt with.

We can see that Youtube is the primary medium being used to address the various Overwatch communities in question. The social influencer of the video being lead developer Jeff Kaplan is a figurehead that the majority of the player base look up to, and hearing him say that reporting toxic behaviour in Overwatch is a good step to ridding the toxicity problem in Overwatch makes the communities in question listen to this, and thus form their own opinions and ideas behind this. This in turn changes the overall attitude and behaviour within the various communities found in Overwatch into an attitude that is committed to neutralising and reducing bad player behaviours within the game. This video and the reactions of the individuals within the specific Overwatch communities that this video targets is a clear cut example of how various, niche communities still relate to one another via a singular purpose, and how the power of social influence has the ability to change specific attitudes and form opinions within communities.

Overall, there is a distinct correlation between online gaming, and the formation of communities and the individuals that associate themselves with online games. The various opinions, thoughts and values that are shared between members of online game communities are generally shared, with a few principle outlying values creating certain niche communities within a generalised community focusing on an online game. These opinions, thoughts and values are subject to change with the input of social influencers altering these already existing opinions, thoughts and values, and thus influence which type of community an individual may choose to associate themselves with. However, the already underlying thoughts, values and opinions that represent the entire, generalised community still exist between various niche groups, and thus allow collaboration and unity between these groups whilst retaining a sense of uniqueness present in the various niche groups found within a community.

- Chua, A. Y., & Banerjee, S. (2015). Understanding Review Helpfulness as a Function of Reviewer Reputation, Review Rating, and Review Depth. Journal of the Association for Information Science & Technology, 66(2), 354-362.

- Domahidi, Emese & Festl, Ruth & Quandt, Thorsten. (2014). To dwell among gamers: Investigating the relationship between social online game use and gaming-related friendships. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 107–115. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.023

- Gusfield, J. R. (1975). The community: A critical response. New York: Harper Colophon.

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of Community: A Definition and Theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6-23. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e5fb/8ece108aec36714ee413876e61b0510e7c80.pdf

- PlayOverwatch (Official Game Development Youtube Account). (2017, September 13). Developer Update | Play Nice, Play Fair | Overwatch [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rnfzzz8pIBE

- Wagner, Michael. (2006). On the Scientific Relevance of eSports. 437-442. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220968200_On_the_Scientific_Relevance_of_eSports

- Warmelink, H., & Siitonen, M. (2011). Player Communities in Multiplayer Online Games: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Proceedings of the 2011 DiGRA International Conference: Think Design Play, 6, 1-21. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3acd/d7a7402cf8c517350f9f6041c29e4b0f34ed.pdf