Abstract

Young teens are embracing the video looping mobile application TikTok as a creative way of engaging themselves and their peers in political issues and debates. Users of TikTok are using the potential power of weak ties within the social network to reach a wider audience which has the ability to promote democracy. TikTok enables teens to network and collaborate with its socio-technical features by creating a Third space for teens to negotiate and articulate their social values and subvert from hegemonic narratives regarding these values. Both impression management and identity performance support activism in both online and offline contexts provided the individual’s identity aligns with their social values consistently. A study by Lane & Dal Cin (2018) found public sharing of prosocial behaviour leads to more participation in activism in both online and offline worlds. This supports the Marxian and Tonniesian sociologists’ theory of a collective and cooperative collaboration in forming communities that has the potential to transcend capitalism and social hierarchies if it wasn’t commodified. Whilst TikTok may appear messy and unorganised to a new user, teens are negotiating this Third space by realising how to reach a wider audience and to draw strength from those that “follow” and “like” their videos about their political views and actions in the hope that others will to.

Keywords: digital communities, impression management, weak ties, Third space, TikTok, teens, activism.

Introduction

Whilst most Social Networking Sites (SNSs) have the ability to share videos on their applications (app), TikTok is a mobile app that is built on short looping videos and the sharing of these videos is its primary focus. With most smartphones having a front facing camera that allows users to self-document their lives, teens are now creating videos that are becoming a “mainstream cultural practice” (Mascheroni, G., Vincent, J., & Jimenez, E, 2015). The TikTok app is free to download on both Apple and Android app stores, and it has easy to use video editing tools embedded in its “create” tab that will allow anyone with limited technology knowledge to create videos, making access very easy for any user to work its connection capability features. Participation can be easy too as it is socially acceptable to be an audience member; or a performer; or both, and an individual can choose how much they want to engage with other users. Lately, TikTok has gained attention in mainstream news articles on how teens are utilising the SNSs to voice their opinions on social issues that matter to teens (Bogle & Edraki, 2019; Lorenz, 2020; Price, 2019). Teens are using comedy sketches or other creative ways to be insubordinate to dominant narratives that perpetuate stereotypes and restrict young teens being heard on political issues that matter to them such as climate change, racism and human rights (Edirisinghe, Nakatsu, Widodo & Cheok, 2011, p. 124). TikTok activist users can quickly build up a large and diverse network of followers with which they can support and empower each other as the algorithms within TikTok affords users the ability to reach many weak ties, whilst young teens can experiment and receive feedback regarding their self-identity. This paper examines the “socio-technical” features of TikTok and the user engagement that support identity performance of young teens and the forming of digital communities within the app. Social networking Sites such as TikTok provide opportunities for young teenagers (13-18 years old) to engage with political issues and form activist communities.

Connection capabilities

The TikTok application utilises a variety of “socio-technical features” that enables young teens to establish and maintain a coherent network of relationships that support the formation of political activist communities (Porter, 2015, p.165). The connection capabilities within the TikTok app are varied and are quite different from other SNSs, in that, the communication is built on young teens’ similar interests performed within a video format where teens focus on creating content as a way of self-expression rather than connecting with friends or friends of friends through stories (Anderson, 2020, p.2). For example, when watching a TikTok performer’s video, there are a variety of ways to search for similar interests. When tapping on the music icon, the app displays all the videos with the same soundtrack. The hashtags displayed on each video play a vital role in communication, as users categorise their videos with the same hashtags for better visibility within the app. (Herrman, 2019, para 6). When watching a video, the user can swipe left to see the video performer’s profile and tap to follow the performer. There is also the discover tab at the bottom of the app, and when typing in “activism” or other keywords in the search bar, potentially, all the videos associated with this topic are shown to create an online space for teens to add more videos with their hashtags or to comment on each other’s individual videos. Most importantly, the app uses artificial intelligence to distribute videos to its main newsfeed which is labelled the “for you” content page. These algorithms are based on which videos a user has watched often and/or “liked” with the heart icon (Jackman, 2020, para.8). These connection capabilities allow teens on TikTok to quickly gain an audience regardless of who they are following or who is following them (Anderson, 2020, p.2). For example, Tara Bellerose (@tarabellerose) who lives in rural Victoria, Australia, is taking advantage of the TikTok app and its connection capabilities to highlight her concerns and protests over the climate change debate. Bellerose’s videos offers other young teen’s practical ways of participating in saving waste and caring for the environment that appeals to young viewers (Bogle & Edraki, 2019). Although Bellerose lives in a remote area of Australia, with the affordances of TikTok she is able to communicate with peers beyond her physical location about her interests on climate change and find user’s with similar interests on TikTok.

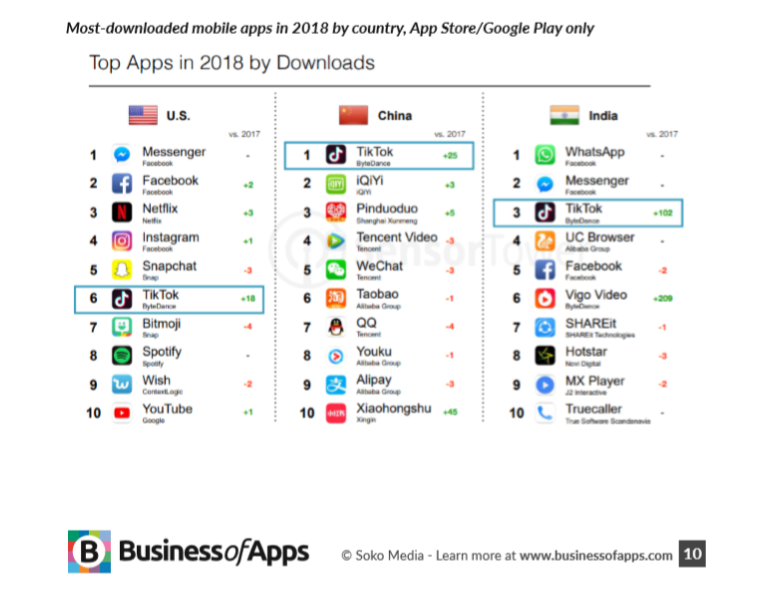

Business of Apps. (2020). https://www.businessofapps.com/

The power of weak ties

The social structure of TikTok can look confusing to new users because its focal point is not on displaying friendships and networks. TikTok’s greatest strength is that it relies on the users’ videos to be shared and watched on the app’s newsfeed (“For you” page). This format is to reach as many individual nodes within the apps’ network which then encourages weak ties to communicate with each other and creates a vast diverse network of users to become a digital community (Herrman, 2019, para 15; Pearson, 2009, para 25; Porter, 2015, p.164 & 165). Weak ties require less emotional engagement and intimacy than strong ties but are useful when sharing information online. Pearson (2009, para 18) states “Weak ties link us to the furthest nodes in a network (Granovetter, 1983) and are vital for broad heterogeneous network cohesion.” Each TikTok user can choose their level of engagement and it is socially acceptable to be either a performer; or an audience member of other performers; or both (Pearson, 2009, para 25). It is easier to maintain weak ties through mediated performative spaces (Pearson, 2009, para 26). The ability and function of an online space in forming vast and diverse networks is the vision that Sir Tim Berners-Lee had in mind when he invented the World Wide Web in 1989 and the teens of today are using these mediated spaces to assert their rights as digital citizens which is also stated and supported in the United Nations’ convention on the rights of the child (Green, 2020, p.6). One example of this is in November 2019, a young American Muslim teen girl (@ferozaaziz) went viral in global news media for sharing a TikTok video posing as a regular make-up tutorial with a message to urge the viewers to search online on how Muslims are being mistreated in China (Wong, 2019).The video has since been viewed over three million times. TikTok users are growing rapidly, with 50 per cent in the 16-24 years old age bracket in the US, but also within other age demographics, such as 25 per cent aged 45-64 years old, and if you add to this the user growth in a wide variety of geographical places as well, India and China recorded the highest user numbers overall (Iqbal, 2020). TikTok has the potential for young teen activist to reach a very wide audience on a global scale with the use of weak ties and cooperation.

Empowering teens in the third space

Online spaces are becoming the only space where teens are able to gather in large groups to converse with their peers without adult supervision (boyd, 2007, p.132; Hodkinson, 2017, p.276) and where teens can speak openly about the political issues that are affecting them (Green, 2020, p.14). A young teen’s private bedroom is the only space—that is considered to belong to them— where they can be free and safe to express themselves (Hodkinson, 2017, p. 274). There is growing discourse surrounding the protection of children and young teens in online spaces but there are also many scholars whom argue for children and teens’ advocacy in accessing SNSs and supporting their participation in these online spaces (boyd, 2007, p.137; Bers, Doyle-Lynch & Chau, 2012; Green, 2020, p. 15). Bers, Doyle-Lynch & Chau (2012, p. 130-131) argue that young teens need to be provided with a positive technological development framework that will support teens to further explore intrapersonal characteristics such as competence, confidence and character with interpersonal skills that promote caring, connection and contribution that will support their online technological skills and civic engagement. SNSs like TikTok provide teens with a Third space in which to speak their voice and where others can “contest, negotiate and rearticulate” the social issues that are affecting them in the offline world. This Third space is both real and imagined where both online and offline communication converges and is captured (Edirisinghe, Nakatsu, Widodo & Cheok, 2011, p. 123-124). Digital communities provide young teens with a Third space to experiment with alternative forms of community, self-representation, reflection and an understanding of ethical behaviour towards other people (Green, 2020, p. 9). The reflexive process of constructing and reconstructing an online identity is how young teens learn to interact with peers online. Identity formation is not a fixed singular representation of who we are—instead we all have many facets to who we are, and how we display these parts of our identity will depend on who and where we are interacting (van der Nagel, 2015, para 10). The contextual circumstances surrounding a person is what influences how they behave, and these circumstances can often interpellate the person into a cultural stereotype without them realising (van der Nagel, 2015, para 12). Teens on TikTok are very cleverly subverting from these cultural stereotypes when presenting their videos as a satirical view of the situation. One young teen Eshia (@eshiaanderson1) from Adelaide, Australia, uses comedy to highlight the racism that she has dealt with in her offline life as an Aboriginal person and has over fifty one thousand followers as a result (Price, 2019). Cardon & Cardon (2007, p.62) argue that communication with weak ties enables better democracy online as individuals that are marginalised in the offline world can speak their voice in the Third space of SNSs. TikTok is providing young teens with a Third space to negotiate their identities whilst learning how to be reflective and advocate for their rights to a public audience.

The public act of sharing and identity performance

Young teens are learning the process of “impression management” when performing their identities on TikTok. Young teens are learning to make meanings from social situations, not only in the online space, but equally in their offline lives—where teens reflect and evaluate other people’s reactions to their videos and adjust their behaviour according to the feedback received (boyd, 2007, p.128). Lane & Dal Cin (2018, p. 1526) argue “sharing social and political views online is in fact a highly delicate matter.” TikTok is a visual means of communication where the performer uses their body to convey the message and project certain information about themselves such as ‘movement, clothes, speech and facial expressions’ (boyd, 2009, p.128). TikTok users are aware that there is an invisible audience especially if their profile is set to public (Pearson, 2009, para 10) and will often perform for a particular audience as it is necessary for an effective performance (Hodkinson, 2017, p.277). One aspect of their identity performance is the curating of their profile page. Hodkinson argues (2017, p.284) the importance of a fixed customisable profile is no longer needed as users engage with a “timeline through searching, examining, reminiscing, editing and shaping.” TikTok users have very limited information on their profile pages, and instead focus on the accumulation of videos in their profile album archive as a self-reflective process (Hodkinson, 2017, p. 274). A TikTok profile page is similar to a Twitter or Instagram profile page as they all display the users’ name, handle, picture and bio. It is socially acceptable for the users to play around with their name and bio over time provided the social values of the person communicating about a social cause remain consistent (Lane & Dal Cin, 2018, p. 1526). A study conducted by Lane & Dal Cin (2018, p. 1535-1536) found that if a disengaged young person shares an initial act of observable activism online then they are more likely to participate in future acts of activism both online and offline, therefore contesting the negative views of “slacktivism”. “Impression management” requires sociality with a group of people in order for individuals to learn what is acceptable and what is not. Teens are deliberately communicating their political views as a means of connecting with a digital community through the process of impression management of their individual identity and the social causes that they support, in the hope that the offline world will change.

The replicability of TikTok and political debate

Teens engage with SNSs like TikTok because “it enables self-expression, enjoyment, information sharing, and relationship building” whilst helping others (Porter, 2015, p. 168) and one of the most captivating properties of TikTok for young teens is how it enables users to replicate other users’ videos within the app (boyd, 2007, p. 126). Young teens will often replicate the behaviour seen on TikTok whether it be a dance, a challenge or a comedy sketch—and if the individual has some self-awareness in whether they are being interpellated, they will relate the original video to their own issues or ideas. TikTok also has the replicating feature where a user can duet with the original video. This allows young teens to star alongside their idols in online spaces. Some teens have used this feature as a way of conducting a political debate in online spaces. For example, in the US, young teens have been participating in virtual online political and ideological groups called hype houses on TikTok where conservatives (@conservativehypehouse) and liberal (@liberalhypehouse) supporters can make videos that highlight the pros and cons of voting for one candidate over the other in a fun and often comedic way (Lorenz, 2020).Whilst it can’t be said that TikTok is a perfect example of a not-for-profit or non-commodified network due to advertisements within the app, it can still provide a space for cooperative sharing where the social hierarchies of the offline world are dissected and critiqued upon. The ownership and production of content is based on collaboration of a cooperative society similar to the views of sociologist Karl Marx and Ferdinand Tonnies whom first developed the idea of human collective cooperative production and the forming of communities to shape one another (Fuchs, 2010, p. 784). The TikTok Social Networking Site has the ability to sustain engagement with the use of its’ “socio-technical features”, in particular it’s connection capabilities, and with users’ frequent interactions centred around the replicability properties of TikTok, making it a SNS that could be around for longer than its predecessors such as Vine and Music.ly, and that potentially sustains young teens active participation in digital communities and activism (Herrman, 2019).

Conclusion

The social networking platform TikTok is proving to be a different way for people to communicate online and form digital communities. Its connection capabilities are strongly embedded in its use of hashtags and its replicability of content. Although it is used for mainly fun and social purposes, it does provide young teens with an online space to voice their opinions and concerns regarding issues that are normally in the adult domain, but that have an effect on a young person’s life. Teens find social networking sites to be engaging and meaningful to their social lives and spend time on TikTok to learn more about their identity through the act of watching, sharing and performing their identities with other peers. The digital communities might appear messy and unorganised to a new user of TikTok, but teens are negotiating this Third space by realising how to reach wider audiences and to draw strength from those that “follow” and “like” their videos about their political views and actions. As young teens become empowered by their audience the possibility of making changes in the offline world might just become more prominent and lead to social change.

References

Anderson, K.E. (2020, February 8). Getting acquainted with social networks and apps: It is time to talk about TikTok. Library hi tech news. DOI: 10.1108/LHTN-01-2020-0001

Bers, M., Doyle-Lynch, A., & Chau, C. (2012). Positive technological development: The multifaceted nature of youth technology use towards improving self and society. In C. Carter Ching & B. J. Foley (Eds.), Constructing the self in a digital world (pp. 110-136). Cambridge university press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/detail.action?docID=1024997

Bogle, A & Edraki, F. (2019, September 19). Students are fighting climate change, one TikTok video at a time. ABC news. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-19/tiktok-youth-led-climate-activism-school-strike/11520474

Boyd, d. (2007). Why youth heart social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life. School of information, 119–142. DOI: 10.1162/dmal.9780262524834.119

Cardon, D., & Cardon, C. (2007). The strength of weak cooperation: An attempt to understand the meaning of Web 2.0. Communications & strategies, 65(1), 51-65. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/4581/

Edirisinghe, C., Nakatsu, R., Widodo, J., & Cheok, A.D. (2011, October). Conceptualizing third space in networked social media [Paper presentation]. Second International Conference on Culture and Computing, Kyoto. DOI: 10.1109/Culture-Computing.2011.31

Fuchs, C. (2010). Social software and Web 2.0: Their sociological foundations and implications. In S. Murugesan (Ed.), Handbook of research on Web 2.0, 3.0, and X.0: Technologies, business, and social applications (pp. 764-789). IGI Global. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-60566-384-5.ch044

Green, L. (2020). Confident, capable and world changing: Teenagers and digital citizenship. Communication Research and Practice, 6(1), 6–19. DOI: 10.1080/22041451.2020.1732589

Herrman, J. (2019, March 10). How TikTok is rewriting the world: TikTok will change the way your social media works—even if you’re avoiding it. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/10/style/what-is-tik-tok.html

Hodkinson, P. (2017). Bedrooms and beyond: Youth, identity and privacy on social network sites. New Media and Society, 19(2), 272–288. DOI: 10.1177/1461444815605454

Iqbal, M. (2020, February 21). TikTok revenue and usage statistics. Business of Apps. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/#1

Jackman, R. (2020). How TikTok is changing the world. The Spectator. https://search.proquest.com/docview/2338943327?accountid=10382

Lane, D. S., & Dal Cin, S. (2018). Sharing beyond Slacktivism: The effect of socially observable prosocial media sharing on subsequent offline helping behaviours. Information, Communication & Society, 21(11), 1523-1540. DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1340496

Lorenz, T. (2020, February 27). The political pundits of TikTok. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/style/tiktok-politics-bernie-trump.html

Mascheroni, G., Vincent, J., & Jimenez, E. (2015). “Girls are addicted to likes so they post semi-naked selfies”: Peer mediation, normativity and the construction of identity online. Cyberpsychology, 9(1). DOI: 10.5817/CP2015-1-5

Pearson, E. (2009). All the World Wide Web’s a stage: The performance of identity in online social networks. First Monday, 14(3–2). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/download/2162/2127

Porter, C.E. (2015). Virtual communities and social networks. In L. Cantoni & J. A. Danowski (Eds.), Communication and technology, (pp 161–179). De Gruyter, INC. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/detail.action?docID=1759936#

Price, H. (2019, November 6). TikTok activism: ‘We’re changing the world in 15 seconds’: Why some teens are using short, shareable social media videos to deal with big issues affecting them. BBC news. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcthree/article/fa349327-bdee-489b-ae44-da4f808d82b8

van der Nagel, E., & Firth, J. (2015). Anonymity, pseudonymity, and the agency of online identity: Examining the social practices of r/Gonewild. First Monday, 20(3). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i3.5615

Wong, K. (2019, December 19). TikTok activism: Teen uses TikTok app to shine a light on persecution of Uighurs in China. The Organization for World Peace. https://theowp.org/tiktok-activism-teen-uses-tiktok-app-to-shine-a-light-on-persecution-of-uighurs-in-china/

22 replies on “TikTok Social Networking Site empowering youth civic engagement”

Hi Kelly,

I enjoyed reading your paper and have to say thank you for educating me on the aspects of TikTok – an app I had only heard of but not experienced.

I am left wondering though what makes TikTok more attractive than say YouTube, Twitter or Facebook where they too have video capability and use hashtags for spreading content? And where, for instance Twitter is a widely used space for activism.

Initially I thought it was perhaps more orientated towards teens but then read on where you have put that 50% is 16-24 yo and 25% is 45-64 yo – there’s hope for me yet:) so just wondering what your thoughts are on that?

Hi Lee,

Thanks so much for the feedback. That’s a great question regarding the comparison to other social networking sites. I touched on this topic a little in the paper but you have given me an opportunity to discuss and unpack this further.

I will address the first part of your question on why is TikTok more attractive than YouTube. The difference between these two SNSs is the level of emotional commitment by both the performer and the audience. TikTok users are creating videos using the templates within the app. It’s quick and accessible with only the use of a mobile phone and internet connection compared to YouTube users spending large amounts of money on video equipment to shoot better quality videos that stand out from other YouTubers. Teens making TikTok videos focus on the content without hailing the audience with their own rhetorical speech. Most YouTube videos start with “Hey Guys, Thanks for watching my video and please subscribe to my channel.” TikTok users go straight to the message of the video as a performance regarding an aspect of their identity without sharing too much of themselves with the goal of connecting with followers for the sake of connecting, not for selling products or promoting products. YouTube performers want a large audience to commodify their page and earn money.

See website: https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/how-to-make-money-on-youtube

TikTok and Facebook are very different. Facebook relies on users sharing information with strong ties, people that know each other in the offline world and then attempts to connect them with latent or weak ties which are friends of friends. In order for this to work, Facebook regularly displays and prompts users to find friends as a way of connecting and making latent ties into weak ties with the hope that they become strong ties (Pearson, 2009, para 19). We know that this can cause context collapse when we try to connect with a variety of ties in the one space because we are trying to negotiate our various facets of our identity, e.g. work, family, friends, offline community groups, etc. TikTok differs because it does not display friendship networks. Its primary focus is getting individuals’ videos out to a wide and diverse audience and to encourage users to “like” it and “follow” each other to strengthen the network as a collaborative structure. Connection as a whole network is more important then fragmented networks of friends and support positive democracy.

Twitter and TikTok share similar connection capabilities to each other than other SNSs. The difference with these two applications is visibility of its users. TikTok relies on algorithmic views of videos and users “likes” whereas Twitter still relies on human made networks of friends. I would like to research more into how the artificial intelligence works with the TikTok app as I find this area very fascinating. The hashtags, video soundtracks, and the video templates set up in the “create” tab of TikTok are how users find ways of replicating content to connect with each other. It is very accessible and visually appealing compared to Twitter. I would argue it gives a better context to the message if you consider that most human communication relies on non-verbal cues (body language and facial expression).

See website: https://search.proquest.com/openview/52442af596bbd7cc0220950cc1a9a3f2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2029989

Finally, to answer your question of who is TikTok orientated towards as you mentioned the age demographics quoted in my paper. The main point of the paragraph relating to age and geographical demography of users was to highlight how rapidly its user growth is diversifying. TikTok is for everyone and is available to many countries compared to other SNSs. I will include a graphic in my paper showing TikTok’s ability to be diverse. Whilst it is becoming more widely popular among older users, it is fair to say that teens were the first to adopt this technology because of its fun and accessible content creation features.

Teens need a space that they can be playful with their identities and speak about their own individual truths. There is no guarantee that those in power will listen, much like Donald Trump dismissing Greta Thunberg at the UN climate summit, but young teens need to have a space to call their own and promote a better democratic society. TikTok provides each individual teen to speak about their issues, a social hierarchy is not evident on TikTok.

Hopefully, I have answered all your questions, Lee. If you have anything you want to discuss further please do ask.

Thank you so much for your reply.

Kelly

Hi Kelly,

Thank you, that was an extremely well-detailed informative answer and I can now appreciate why TikTok has gathered in momentum. Especially with, as you pointed out, there isn’t much time or outlay invested in the posting of such video content compared to YouTube.

You do wonder if, with increased usage – and in particular when parents start using it, it will be left behind as another comes on the scene for teens to jump onto? Such as with FB “As soon as parents got in they killed it,” says 24-year-old Jordan Ranford, a now minimal Facebook user who ditched his mum as a friend because she was “just jarring” (Sweeney, 2018). I’ve heard that from other people before.

Thanks Kelly

Sweeeny, M. (2018). ‘Parents killed it’: why Facebook is loosing its teenage users. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/feb/16/parents-killed-it-facebook-losing-teenage-users

Hi Lee,

That’s also relevant to the discussion. How do parents and teens share a digital space without context collapse or feeling like they are being supervised?

What I discovered during my research is that teens are welcoming their parents into their digital lives on TikTok, especially since we are all social distancing at home. There are a few viral hashtags happening at the moment where families are performing TikTok videos together. #livingtogether #daddance #tiktokdad and many other categories.

I think this is because of the video format and how the focus is on performing for a video. The focus is also on having fun and collaborating.

https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/laurenstrapagiel/blinding-lights-tiktok-dance-challenge-parents

On personal note, my daughter also asked me to do a TikTok dance with her last night and we had a lot of fun together. It’s a great way for a parent to show support in their kids’ interests.

TikTok’s appeal to younger audiences may change in the future but it would depend on how parents and teens are connecting and communicating with each other in this space. At the moment, it seems to be a mutual agreement between the two parties. I would argue that TikTok is supporting and strengthening relationships in families during a stressful time. I also think that the United Nations’ convention on the rights of the child in 1989 is having further effects on parent’s respect for children’s rights in society.

https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Events/OHCHR20/VDPA_booklet_English.pdf

Thanks again for your thoughts.

Kelly

Hi Kelly,

Sorry it has taken me a while to get back to you but, like you, needed to get that other assignment done.

I read the United Nation’s report and all the time thinking how much nicer the world would be if we all lived by those codes of conduct. There was a few disturbing elements that they address, such as the sale of children and organs! Horrible!

On a lighter note, this point in the convention: “The World Conference on Human Rights also stresses that the child for the full and harmonious development of his or her personality should grow up in a family environment which accordingly merits broader protection” (p. 14).

which on a lesser scale resonated a little with you saying how parents and kids are using TikTok creating videos together and sharing them online as a bit of family fun. All part of that feeling of unity, belonging and of being valued.

Had to smile when I read about doing a dance with your daughter as it reminded me of a similar experience I had with my mum, many moons ago, and the laughs we had as I tried to teach her the moves to the “bump” as it was called – probably before your time? or maybe it was just a pommie thing?

I also had a read of some of the Investigating Disinformation and Media from the link you put on your reply to Anne-Marie. I haven’t read it all either but what I have has been very interesting and could have been quite a useful resource for some of the other people’s papers that focused on trust (and mine). I’ve saved it for further reading and in case I need it later in other units. Good one to share thanks Kelly. Just out of interest I did Google the author haha and he comes with pretty good credentials! I thought this was pretty interesting philosophy of Craig’s:

“Trust is the foundation of society. It informs and lubricates all transactions and is key to human connection and relationships. But it’s dangerous to operate with default trust in our digital environment.”

Have you got any more interesting links in your repetoire?

Lee

Hi Lee

I have only just installed TikTok on my phone and tablet as I kept getting ads and curiosity got the better of me! Within a few hours I was addicted. It is a lot of fun!

Kelly, it was great reading your paper as I never thought about how TikTok could be used for activism but you showed some wonderful insights into how TikTok is accessible and so simple to create something short yet very effective that can be sent to millions across the world and send a very strong message. As you said Tim Berners-Lee had that vision we should all have an Internet without censorship, and there are many countries where so many things are still considered taboo, and the rights of women and children are still unheard. With one swipe, TikTok allows you to access a new video in an instant, you don’t know what you’re going to see next. You could just happen to come across something that speaks volumes for a minority that are not being heard!

-Indre 🙂

Hi Indre,

Thanks so much for your feedback. I’m glad you’ve discovered TikTok, it is a lot of fun and so easy to participate in.

I’m wondering if you have connected with any users regarding veganism. I’ve noticed a lot of vegan recipes on TikTok and I was hoping you could let me know how they compare with the YouTube videos that you shared in your paper below?

https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2020OUA/2020/04/25/identity-wars-how-the-self-presentation-of-vegan-youtube-influencers-impacts-viewers-and-the-vegan-movement/

I’ve also noticed that because of the satirical nature of TikTok that some vegan videos are being critical of that particular lifestyle. #veganlife I was wondering if that is a good or bad thing? I don’t know much about the vegan diet or lifestyle so it would be good to get your opinions on this from your research.

Thanks

Kelly

Hi Kelly

Sorry for my late reply, I have been meaning to check TikTok for these videos as I have never actually come across them! I guess TikTok has already worked out an algorithm to show me only videos that I am interested in, which at the moment are pets etc so I tend to only see funny videos of dogs or cats LOL… but if I searched for #veganlife I can see what comes up! Since I am not vegan myself I’d probably find most of them funny, though I’m also a believer in “if you don’t have anything nice to say don’t say anything at all”. The videos could also end up spreading misinformation rather than trying to be funny. I’ll have to get onto TikTok later today 🙂

Thanks

Indre

Hey Kelly!

Really interesting and relevant topic today. I also referenced Tik Tok in my essay as I think it’s really important to mention more recent examples! Our examples are definitely different though, I talked more about the dangers of TikTok challenges.

I liked the way you talked about how TikTok has given a platform for adolescents to discuss, it’s definitely a more youth-used app which benefits their community (with less adults watching and moderating!).

I enjoyed the discussion of comedy to actually deconstruct negative parts of our community (eg Eshia’s racism comedy). I can see this in the use of ‘story time” videos where the user tells a story that gets worse and worse, or just the general depictions of comedy to talk about problematic behaviors. It’s a great tool as it definitely gets attention due to being entertaining and also educational.

I really liked how many case studies you used to support your points! It was great to see all the sources referenced through out too, it looks like you did a lot of research. It would have been nice if there was more discussion about a specific community as you mainly focused on individuals, but I did like that you mentioned Hype Houses. I discussed VSCO girls in my paper, and it would have been interesting to explore how the different civic / political communities possibly can cause identity erasure? Do you agree? (As in do certain communities amplify and idealise certain characteristics and ignore the others) I know the word count is definitely a big factor too (I struggled with it!).

You mentioned that TikTok has come after Musical.ly, but TikTok is actually Musical.ly, as Musical.ly was bought and then rebranded. I was really surprised when I found this out but it does make sense as it mimics some of the original features of Musical.ly

Do you think that TikTok’s civic engagement can also be a way to spread misinformation when it comes to politics?

Anne-Marie

Hi Anne-Marie,

Thanks for your questions. The examples I gave in the paper show how an individual person as well as groups can display their identities for the purpose of expressing their political views that are linked to their identities. I’m not sure what you mean by identity erasure? If you could link me to a source explaining this concept?

Thanks for querying the ownership context of TikTok. TikTok owners Bytedance based in Beijing bought Music.ly which was a US based app. It then decided to merge the music.ly app and re-brand it as TikTok, therefore making music.ly redundant.

see website: https://www.theverge.com/2018/8/2/17644260/musically-rebrand-tiktok-bytedance-douyin

In response to your last question, I think teens need to learn how to be critical of the information they receive. I think this is where education which I mentioned in my paper is necessary for teaching young people this vital skill.

See reference: Bers, M., Doyle-Lynch, A., & Chau, C. (2012). Positive technological development: The multifaceted nature of youth technology use towards improving self and society. In C. Carter Ching & B. J. Foley (Eds.), Constructing the self in a digital world (pp. 110-136). Cambridge university press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/detail.action?docID=1024997

When I conducted research for the misinformation question, I searched for the corona virus challenge and the first video to show was the World Health Organization videos to support young teens and others in understanding the importance of social distancing. After that there are many other organizations that are showing ways of supporting the correct information. eg. @unmigration, @worldeconomicforum @ifrc @refugees plus many more.

The other thing that TikTok does well is political satire. I think some politician’s can spread misinformation and there’s plenty of Trump parodies on TikTok that shows how the reverse can happen. Misinformation in the offline world being critiqued in the online world. see @trumpdoestiktok #trump #disinfectant

Misinformation will always be something that we have to be critical of because we live in a democracy that respects individual’s free speech but there are ways of finding credible sources such as health authorities and research professionals that have peer reviewed studies. I recently found this source.

https://datajournalism.com/read/handbook/verification-3

I haven’t had chance to read all of it yet but it discusses possible problems with trying to verify misinformation.

Thanks again for your reply. If you have any other questions please post.

Thanks

Kelly

Hi Kelly,

Your topic has opened my eyes to a part of the SNSs I was not quite aware of. I enjoyed the read and well done! 😊

You mention that youths are exploiting the potential power of weak ties on TikTok which likely promotes empowerment, democracy and creates a third space. I agree.

How are they managing the publicity and attention (or lack of) that comes with SNS profiles? Is there pressure to perform their identities in a certain way that may affect their mental health?

Is pseudonymity affecting the week ties and self-expression of youths on TikTok? Is it an enabler or disabler, do you think?

In my paper, I discuss how pseudonymity is a challenge with regards to authenticity and responsibility. Also, see the thought-provoking comments posted in response to my paper’s standpoint on the subject.

Bayayi

https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2020OUA/2020/04/27/how-pseudonymity-in-online-communities-has-the-effect-of-being-a-double-edged-sword/

Hi Bayayi,

Thanks for reading my paper! I have also read your paper and left a comment on your page. I really like how our papers are very similar in how we consider the affordances of social media and how young teens are managing their online identities. Whilst it may be necessary to be cautious when it comes to teens using social networking sites. I am also aware of the potential negatives of social media but through my offline work as an educator, I can see how children and young teens are asserting themselves in these online spaces. Children and teens are much more aware of how the technology works and they understand the front and back stage performance probably better than adults. One of the trends on TikTok that I have recently seen is people recording a behind the scenes video of how they made a TikTok video. I think these kinds of videos further support teens in their understanding of how to perform an online identity.

Here’s an example @youneszarou or search #tutorial

I cannot comment on how the teens are reacting to the offline media attention. That is something that only they can describe. But as I argued in my paper the teens in the TikTok videos all have public profiles, they are aware that they are reaching a wide audience and it’s possible that the teens mentioned are hoping to becoming viral. Their online identity supports their online network. The more the user communicates, the more followers they have and the more interactions the user has with their followers and networks within the app then this is what further encourages engagement and empowerment. The feedback from the audience is how a teen learns to gain confidence, modify their identity and construct their political message with a meaningful purpose.

I think pseudonymity is enabling young people to speak out about the political issues that are affecting them personally. The fact that they use weak ties allows minimal information about their offline self to be used online. TikTok does not ask for lots of personal information unlike FaceBook which requires many boxes of information about users and stipulates “real” identities in its T&Cs.

“Weak ties require less emotional engagement and intimacy than strong ties but are useful when sharing information online. Pearson (2009, para 18) states “Weak ties link us to the furthest nodes in a network (Granovetter, 1983) and are vital for broad heterogeneous network cohesion.”

Lastly, it is important to recognise that young teens are still developing their identities. Teens are going through a dramatic phase of development in all areas; cognitively, sexually, physically, socially and emotionally. Their offline identities are also going through this process and there are many learning phases that teens will go through before reaching adulthood. So bearing this in mind, there will also be plenty of times that a young teen will make a mistake and take unnecessary risks. Therefore, using a pseudonym allows an individual to make these mistakes without too many consequences.

For example, a famous singer was criticised for posting a racist video on TikTok. She is a public figure and also an adult that should of known better. But what this incident has done is highlight to the public, in particular young teens that use this SNS, that cultural appropriation is an act of racism, even if portrayed as comedy. Hopefully, users will think more carefully before using the soundtrack templates available on TikTok and furthermore, TikTok will review their soundtracks and filters with better cultural sensitivity.

https://musicfeeds.com.au/news/amy-shark-apologises-after-tiktok-video/

Thanks for your questions, Bayayi, they were very challenging!

Kelly

Hi Kelly,

Your Paper really intrigued me. I am not really a fan of tiktok myself, although I have seen a few videos. But I was unawre that users could actually use tiktok to their advantage and create a space for political dabtes and activism. I just know tiktok for being a space for sharing dance or comedy videos. I find to very interesting that users can incorporate popular aspects like comedy etc to express their opinions with others who share the same views or encourage others to see the importance of their stance. I explore Instagram influencers in my paper and I’m sure we are all aware of inluencers on youtube but would you say that use of TikTok for politics and activism almost introduces a new class of Infleuncers?

I do think that its great that many people are using different social networks to express importance issues in a more creative and engaging way.

Hi Kaitlyn,

Thanks for reading my paper, I appreciate your feedback. During my research, I discovered that a TikTok account can be linked to Youtube and/or an Instagram profile. So it’s worth recognising that the TikTok developers have done this deliberately, maybe in the hope that influencers will adopt the platform and support TikTok in generating advertising revenue.

I think the teens that I provide as examples are sharing their political views in the hope to support positive societal change but like all social media, it is very possible for it to be used for negative propaganda and incorrectly influence others.

Thanks

Kelly

Hi Kelly,

Thank you for introducing me to the world of TikTok! I really didn’t know anything about it, other than it seemed to be growing in popularity and I saw Judy Dench doing a TikTok dance with her son 😊

You’ve written a great paper. I really appreciated the examples you gave throughout to back-up your analysis, as it helped a non-TikTok person like me understand how the theory applies to real life.

In the introduction you say “Participation can be easy too as it is socially acceptable to be an audience member; or a performer; or both, and an individual can choose how much they want to engage with other users”, which prompted me to think about Nicola’s paper on Facebook lurkers. The attitudes of two sites seems to be very different – on Facebook, people not participating could be considered as ‘lurkers’, whereas on TikTok they are ‘audience members’. In her paper, Nicola says, “The profile of a reluctant lurker therefore is that of a socially detached actor, fearing consequences of their actions, feeling socially isolated or excluded, trapped in a state of low flow but high involvement” (Bishop, 2013 as cited in Forbes, 2020, para. 1). I wonder how you view the issue of lurker versus audience member after all of your research?

You also state that “the teens of today are using these mediated spaces to assert their rights as digital citizens” (para. 3). The examples you give go on to demonstrate how this is happening on TikTok, but I was curious to know how (or if) this extends to the offline world. In their papers, Georgia and Bruno consider the role Web 2.0 has played in educating people on Indigenous and feminist issues, but they conclude that education does not necessarily result in action. Do you have any examples of teens being able to convert the traction created on TikTok into offline action? Or are they using the platform as a way to practice and prepare themselves for action when the time is right?

That was a really interesting read and one that I will keep thinking on!

Thanks,

Anna

——–

Forbes, N. (2020, April 26). Lurkers are us: when nothing signifies something [Paper presentation]. Debating Communities and Networks 11. https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2020OUA/2020/04/26/lurkers-are-us-when-nothing-signifies-something/

Hi Anna,

Thanks for reading my paper. Yes there’s a few celebs on TikTok. Great to see Judi Dench TikToking!

You ask some really interesting and challenging questions for me to unpack.

Firstly, “I wonder how you view the issue of lurker versus audience member after all of your research?”

I think this would depend on what is the definition of a lurker. The identity of a lurker is in relation to whether someone is seen as trustworthy and authentic. As Nicola describes in her paper, ” the profile of a reluctant lurker therefore is a socially detached actor, fearing consequences of their actions, feeling socially isolated or excluded, trapped in a state of low flow but high involvement (Bishop, 2013).”

The Macquarie dictionary gives a definition of the word “Lurk” as “to remain or be in or about a place secretly. To move with secrecy; slink; steal.”

Pearson (2009) states “these actors [people who post content] are (to a greater or lesser degree) aware of both other users as well as the ‘audience’ of lurkers, virtual passer-bys, and wider social networks.” para 10

If we take these statements and position them in relation to one another, I would argue that the term ‘audience’ can be a variety of SNS users with a lurker being one particular type.

If we consider the audience on TikTok’s network and what is required to make TikTok users have a successful networks, it requires a large audience and it’s technical features of the newsfeed ‘for you page’ and the discover page are set up to allow anyone to see a public profile. The app requires users to watch each other as way of forging engagement and connection between weak ties of unknown users. There is probably lurkers on TikTok but I would argue that it only becomes problematic if their user intentions are harmful and/or illegal.

When speaking about the issue of lurking, it’s also worth remembering that anything a person posts can be remixed and replicated onto other social networking sites so it’s wise to think carefully before we post because someone with ill intentions could screenshot or photoshop images or videos and re-post on other sites. It’s also worth noting that TikTok users can turn off comments on their posts if they are worried about lurkers. I found this article to be interesting on the subject.

https://theconversation.com/trolls-fanboys-and-lurkers-understanding-online-commenting-culture-shows-us-how-to-improve-it-96538

From a parents point of view, this information was also relevant and useful.

https://parenthub.dollysdream.org.au/styles/tech-embracer/

Secondly, “Do you have any examples of teens being able to convert the traction created on TikTok into offline action? Or are they using the platform as a way to practice and prepare themselves for action when the time is right?”

This is a great question and one that needs further research, particularly with specific TikTok users. I think because TikTok is a younger app compared to Twitter and Facebook, it is something academic scholars should focus on. It is something that I will be further researching as I progress in my studies and career.

The media article that I shared in my paper was an interesting one because it highlighted how activist movements are using many platforms to communicate their message, e.g. schoolstrike4climate.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-19/tiktok-youth-led-climate-activism-school-strike/11520474

I would argue that TikTok is seen by many as an online space for young teens which is why there is a large gathering of teens within. The reason I think teens are speaking about the political issues of their choice on TikTok is because there are not many other spaces in which they can do this. Greta Thunberg’s story is a very unique one, and I’m sure many teens aspire to be like Greta but many young teens do not have the same opportunities and offline connections or support that allow a young teen to be in the same physical space as world leaders and speak their mind, the only alternative is to network and gain traction as a collective group within an online space.

Teens are not old enough to vote for a leader who constructs and advocates for policies on their behalf but hopefully the engagement during this period of their lives is enough to spur them on through to adulthood and do so. The study I quoted in my paper was from a cohort of 185 students from a public university in the US where they were asked to review and evaluate three not-for-profit charity organisations and state which one they were likely to support. The study then showed a social cause video on the participants’ facebook wall, some anonymously and others publicly. What the study found was those that shared publicly were most self-consistent with their actions and identity presentation aligning with the same moral values and this one act of sharing is more likely to lead to further activism (Lane & Cin, 2018, p. 1535-1537).

Lane, D. S., & Dal Cin, S. (2018). Sharing beyond Slacktivism: The effect of socially observable prosocial media sharing on subsequent offline helping behaviours. Information, Communication & Society, 21(11), 1523-1540. DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1340496

Lastly, I think it is worth noting that social media sites change over time and there is this interplay between the technology and culture where both are shaping and changing the way we communicate (Burgess & Baym, 2020, p.21).

Burgess, J., & Baym, N. K. (2020). Twitter : A biography. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com

It will be interesting to see how TikTok evolves through time and by its users and how this shapes our society and political engagement.

Thanks for your feedback.

Kelly

Hi Kelly,

Thanks for such a detailed response! It’s clearly an area of great interest for you and one that you’re very passionate about.

You’ve given me a lot to think about. I think your final point about the interplay between technology and culture is a really interesting one and one that I will continue to think on long after the conference is finished!

Thanks again!

Anna

Hi Kelly,

I really enjoyed reading your paper, great topic! Maybe I am a little biased because I love scrolling through TikTok in my down time and also wrote my paper on digital activism. All in all, I really enjoyed your writing and structure of your essay.

While I like to endlessly scroll on TikTok, I must say I struggle understanding how it works regarding making videos and also how videos land on the For You Page, thanks for providing an insight into the ever growing, ever popular app. The use of weak ties to reach a mass audience is very interesting, it really doesn’t compare to Instagram or Facebook at all as visibility on those apps for regular users seem to be overlooked by popular creators and influencers or unseen due to restrictive visibility.

Do you think TikTok is an equally or more powerful app than Twitter for teens participating in digital activism? As TikTok is more closed off to non-users outside of the popular age bracket on the app, do you think TikTok has the power to create real social change when the information is mainly circulated on the app? Its sort of like an echo-chamber where the users of the app are the only ones who may see it, I wonder if this platform has the power to reach the wider population like Twitter can.

Thanks again for a really interesting paper, it is evident you put a lot of effort and research into it.

Laura

Hi Laura,

Thanks for commenting on my paper. It’s interesting that you bring up the issue of visibility on various SNSs, I’m certain there are users on TikTok that are not as visible as others, it all depends on how the algorithms work and whether users are utilising the hashtags to great effect.

I think TikTok is an SNSs for young people more than Twitter. This paper below shows a decrease in users on Twitter within the 18 to 29 year olds demographic. I’m not sure exactly how accurate these numbers are but it does suggest that young people are moving from one platform to another with not much loyalty to any SNSs. Maybe in the hope that they can move away from their parent’s watchful eyes as Lee mentioned her comments above in regards to Facebook.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2056305117691544

In regards to your question about TikTok being a closed app, I would argue the opposite. TikTok has the ability to share its content on other SNSs, making it an open interface. For example, when a user is watching a video, they can tap on the share icon (the curved arrow button) and a list of options appears at the bottom of the screen. Videos can be shared on other SNSs like Twitter, Snapchat, Whatsapp, Instagram, Facebook, SMS, messenger and more. Furthermore, users can save any video to their mobile device, or perform a duet or reaction video or share the video as a GIF. So there are plenty of options to share TikTok content in a variety of ways provided the video is set to public.

In response to your query about TikTok becoming an echo chamber where users replicate content, I would agree but I would also state that this is what supports impression management of people’s identities. The replicability of TikTok is how young teens are constructing their identities. They are signifying to other users through the use of their bodies, clothes, comedy, political statements, etc that they are either the same or different from other users and that they belong to a particular group who also identify with the same symbolic features. It’s a very powerful socio-technical feature of an SNSs that has the power to bring users together – or like in Indre’s paper on vegan communities- fragment communities.

Thanks again for your questions, I appreciate your feedback.

Kelly

Hi Kelly,

Thank you for an enjoyable read! I have to admit I am a 25 year old that loves Tik Tok (haha), so I loved learning more about the app!

Here are some of my thoughts –

1. “Teens are using comedy sketches or other creative ways to be insubordinate to dominant narratives that perpetuate stereotypes and restrict young teens being heard on political issues that matter to them such as climate change, racism and human rights (Edirisinghe, Nakatsu, Widodo & Cheok, 2011, p. 124).”

– This is very true. Did you see the recent viral Tik Tok video of the teen lip syncing to Scott Morrisons press conference? It was hilarious and apparently even Scomo liked it!

2. “There is also the discover tab at the bottom of the app, and when typing in “activism” or other keywords in the search bar, potentially, all the videos associated with this topic are shown to create an online space for teens to add more videos with their hashtags or to comment on each other’s individual videos.”

– Do you think this is an effective way that Tik Tok users create community or is this just a good way to search for content and network?

4. “Young teens will often replicate the behaviour seen on TikTok whether it be a dance, a challenge or a comedy sketch—and if the individual has some self-awareness in whether they are being interpellated, they will relate the original video to their own issues or ideas.”

– This is why I really enjoy Tik Tok – you can be as creative as you want to be or you can simply replicate other users content and still be able to create something appealing to the Tik Tok audience.

5. “For example, in the US, young teens have been participating in virtual online political and ideological groups called hype houses on TikTok where conservatives (@conservativehypehouse) and liberal (@liberalhypehouse) supporters can make videos that highlight the pros and cons of voting for one candidate over the other in a fun and often comedic way (Lorenz, 2020).”

– Wow this is very interesting – I will have to check out these accounts. Do you know if these accounts are associated with THE Hype House (where Tik Tok stars live together in LA – like a content house)?

All in all, I really enjoyed reading your paper and loved learning about how teens are using Tik Tok in a positive way which is potentially leading to social change.

Emily

Hi Emily,

Thanks for your positive comments, I’m glad you enjoyed reading my paper. That’s great that you gained some more knowledge and insight about TikTok as a user from my paper. It’s probably one of the more creative SNSs available.

In regards to question 2, yes it is both. It is how the app groups the videos together and it is also where other users can respond to the videos, either comment, like or share in a variety of ways that I mentioned in my response to Laura. And it is how users find, connect and follow other users.

The sense of community depends on the level of engagement and the individual’s own ideas of what they think is a community. The word community gets used in various contexts, for example, I was at my local mall recently and saw a sign on a shop window that addressed its customers as the shop’s community. I bought Pj’s from there once for a relative, does this make me part of the shop’s community?

I think researching more on community and networks is something I will be doing for the final assignment but I think after this conference I have a better understanding now of the differences and similarities.

With your last question about THE TikTok hype house, unfortunately the two are not connected. The political hype houses took the concept and made them a virtual hype house. Imagine if the two were connected and what that would do for their audience numbers! Definitely have a look at them, interesting topic. Try this link here, it has other handles and hashtags to follow up on.

Lorenz, T. (2020, February 27). The political pundits of TikTok. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/style/tiktok-politics-bernie-trump.html

Thanks again

Kelly 🙂

Hi Kelly,

No worries, thanks for your response.

Yeah definitely. The search bar is an affective tool in connecting people, especially as they will follow/like/comment if they enjoy the content of the other user. Sometimes I’ll enjoy one video that I see on my Tik Tok feed and follow the person even without checking out the rest of their videos on their profile.

I see what you’re saying there. I don’t think I’d necessarily feel apart of a community just from making one purchase. However perhaps if I was invited to a mailing list that offered perks and special offers, I may feel more connected.

I also feel more equipped to answer the final essay questions after this conference. It has been a real eye opener and I have learnt so much! I thought the conference would be a little tedious but I have actually really enjoyed the whole process!

That’s so interesting. I wonder if the LA ‘Hype House’ got the idea of the name from the political hype houses you spoke about. I will definitely have a further look into this. Thanks so much for the link!

All the best,

Emily