⚠️ CW – Discussion surrounding:

- Extremist ideologies; alt-right and white nationalist movements

- The Christchurch mosque shootings

- Racist, xenophobic, and misogynistic rhetoric

- Hate-based violence and discriminatory content

Introduction

When a broadcast comprised of white nationalists debating ’race realism’ was briefly the most popular live-streamed video on YouTube, concern grew regarding YouTube’s role in disseminating extremist content and encouraging political radicalisation (Lewis, 2018). With 2.5 billion active monthly users, YouTube is amongst the most popular social media platforms. It has been at the forefront of many concerns that social media platforms promote increasingly extremist and divisive content to users (Haroon et al., 2020). One typically divisive group that YouTube hosts is the alternative-right (alt-right) network, a group whose exact beliefs vary significantly from liberalism to white nationalism but is unified by its contempt for current social justice movements and progressive politics (Lewis, 2018). Recognising that “…media also shapes identity” (Pariser, 2011, p.23) and that over 70% of the content viewed on YouTube is recommended by YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, algorithmic bias can play a significant role in shaping users’ worldviews and self-contextualisation (Rodriguez, 2018, as cited in Harron et al., 2023). This paper argues that YouTube’s recommendations algorithm disproportionality recommends alt-right political ideologies and intensifies users’ selective exposure through filter bubbles, increasing the likelihood of affective polarisation and political radicalisation. This is achieved through algorithmic biases, the incentivisation of commercial populism, and the creation of filter bubbles that encourage in-group thinking and “othering”, exemplified in ex-alt-righter Casey Cain’s testimony and Christchurch shooter Brenton Tarrant’s actions.

Table of Contents

Packaging Radicalisation

A key reason behind YouTube’s recommendation algorithm’s disproportionate proliferation of increasingly extreme content is the alt-right’s ability to understand YouTube’s culture and affordances. Alt-right creators package content in a manner that ensures it is advanceable by YouTube’s recommendation algorithm. YouTube’s audio-visual content delivery is ideal for populist content, which relies predominantly on ethos rather than evidence (Wurst, 2022). This format allows a more personalised delivery and a captivating, satirical tone, which aligns well with YouTube’s culture and entertainment purposes (Evans, 2018). This ability of the alt-right network to present their ideology in a light-hearted manner through the use of memes and degrading jokes further helps advertise an identity as ‘edgy’ and ‘counter-cultural’, providing a ‘punk-like’ appeal. By packaging extremist ideas in this digestible comedic manner, audiences can become gradually desensitised towards the presented attitudes (Lewis, 2018). This presentation of the alt-right is aided by YouTube’s audio-visual affordances and its alignment with YouTube’s YouTube culture of memes and satire, allowing increased engagement and better ranking within the platform.

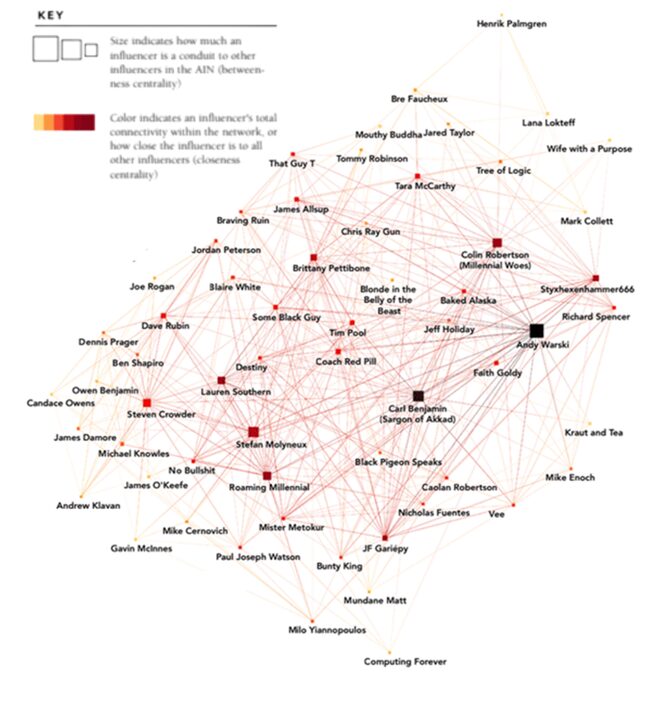

Another method by which alt-right ideology is algorithmically favoured is by their ability to platform themselves as an interconnected network. Alt-right content creators frequently collaborate and appear as guests on different channels. The scale and interconnected nature of the alt-right network is illustrated in Figure 1. By hosting other right-wing influencers as guests, the channels facilitate easier flow from one video to another, often through proliferation and direct links to content, increasing their audience and exposure (Lewis, 2018). By creating a network of guest appearances, there is an increasing overlap between conservative and more extremist influencers, creating a “radicalisation pipeline” (Ribeiro et al., 2020, p.1) by which users can travel to find increasingly extremist content. These collaboration strategies provide a comprehensive network from which the algorithm can draw, contributing to algorithmic overrepresentation.

Figure 1

Documenting the Alternative Influence Network on YouTube

Note. Adapted from “Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the reactionary right on YouTube,” R. Lewis, 2018, Data & Society, p.11 (https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DS_Alternative_Influence.pdf). Copyright 2018 by Data & Society.

Profit-maximisation

As it operates within the attention economy, YouTube’s recommendations algorithm optimises user engagement to maximise its advertising value and potential revenue from third parties. To track the recommendations algorithm’s success, YouTube measures engagement using “captivation metrics” (Seaver, 2018, as cited in Milano et al., 2020, p. 962), such as video views, ‘watch times’, likes, shares and comments. Before 2012, YouTube’s recommendations algorithm used ‘views’ as its primary indicator of video quality and popularity (Goodrow, 2021). However, this cultivated a mass of ‘click-bait’ videos, and to combat this shift, YouTube amended the algorithm to centre around ‘watch-time’ to rank videos based on the content’s ability to sustain user engagement (The YouTube Team, 2019; Covington et al., 2016). YouTube’s algorithm has elements that remain relatively opaque, as it has integrated a “neural network” (Byrant, 2020, p.3), which is a machine-learning system wherein more obscure patterns between content are identified, and recommendations are automatically adjusted accordingly (Byrant, 2020). These amendments were made to maximise user engagement and the platform’s profitability.

Over 70% of the content viewed on YouTube is recommended by YouTube’s recommendation algorithm. (Rodriguez, 2018, as cited in Harron et al., 2023)

Building the pipeline

By prioritising user engagement and locating these underlying connections, many of these algorithmic adjustments built the pipeline to the alt-right. Bryant found strong biases in the recommendations algorithm to promote right-leaning content, most notably that of the alt-right (2020). This research is supported by Harron et al. (2023), who found that content was increasingly recommended from “problematic” (p.1) channels, whether they be alt-right, populist or conspiratorial, with over 36.1% of users encountering them. One explanation is that the changes to focus the algorithm on ‘watch-time’ suited the alt-right creation style as predominantly long-form content of debates, podcasts and video essays. As alt-right content was often interwoven into pop culture commentary or game reviews, the new incorporation of AI to link content based on otherwise indiscernible parallels meant that this content further acted as a gateway for users to the more explicitly political and radical alt-right ideologies.

In adherence to optimising users’ time spent on the platform, YouTube financially incentivises content creators through the YouTube Partner Program and ‘super-chats’, providing avenues for full-time careers for alt-right creators and rewarding populist content. YouTube’s algorithm is engagement-oriented, meaning that sensationalised and controversial content receives a financial reward, monetising and incentivising extremer content for it is more likely to increase views and profitability. The YouTube Partner Program allowed all creators to receive a portion of ad revenue when, previously, this was restricted to certain channels that met set moderation requirements (Munger & Philips, 2020). This amendment resulted in more lucrative career opportunities for far-right content creators. It incentivised the creation of more ‘rage-bait’, extreme and populist content, or “commercial populism”, to retain users’ attention (Volcic and Andrejevic, 2022, p.1, as cited by Wurst, 2022). In 2019, YouTube demonetised political channels to prevent the association of advertising brands with extremist channels (Munger & Philips, 2020). However, creators continued to have access to content monetisation through ‘super-chats’ on live streams, crowdfunding sites like Patreon, and direct product promotion and advertising in their content (Munger & Philips, 2020). This enabled full-time careers out of the production of controversial content, resulting in commercial populism and allowing for an even more saturated market of extremist content.

38% of fascists who credited the internet explicitly credited YouTube for their ‘red-pilling

Evans 2018

An Algorithmic Push

As YouTube’s recommendations algorithm amplifies echo chambers into filter bubbles and constricts the diversity of opinion and information that alt-right users encounter, the abundance of extremist content supplies an alt-right tunnel. When engaging with political news and information, audiences tend to build their echo chambers through selective exposure and confirmation bias, but by sourcing political information from YouTube’s recommendations algorithm, the agency of this exposure is transferred onto the algorithm, and a filter bubble is created (Selvanathan & Leidner, 2022). Audiences are most prone to selective exposure to political topics, seeking material reinforcing their pre-existing political beliefs, which are then used to process said political information (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2023; Stroud, 2008, as cited in Leung and Lee, 2014). For this reason, having a recommendations algorithm designed to categorise users’ interests and feed them political information similar users have engaged with can cause a bias-affirming feedback loop that shelters users from rebuttals (Haroon et al., 2023). It creates an environment wherein each user lives in their own “unique universe of information” (Pariser, 2011, p.10), and messages reaffirming reactionary politics are pushed; counter-arguments routinely subsided (Jamieson & Capella, 2008, as cited in Arguedas et al., 2022). This diminishes the common ground between parties, and the limited exposure to alternate views lowers tolerance for alternate opinions and reinforces the more extreme worldview (Arguedas et al., 2022).

One of Us

The alt-right network is an affective public connected by the solidarity of anti-progressive sentiment; it offers belonging and solidification of social and political identity and bolsters an in-group mentality coupled with YouTube’s algorithmic-induced filter bubbles. The alt-right is an affective public in that it is connected through expressions of anti-progressive sentiment, supports connective action, and is disruptive of dominant political narratives (Papacharissi & Taylor, 2023). By centralising the alt-right identity around contempt for ‘progressives’, it defines the in-group identity as based on supremacy over the ‘social justice warriors’ and feminists outgroup. The alt-right presents itself as having a fundamental understanding of truth, and by accepting it, the user is permitted into an exclusive network. By identifying and engaging with the alt-right as a networked public, users can adopt and refine their social identities as much as their political identities. It grants a sense of belonging and acquired knowledge (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2023). A popular term used by the alt-right community to describe their first-time embracement of alt-right ideology is ‘Red-pilling’. It references The Matrix and likens the absorption of alt-right beliefs to enlightenment, gaining access to forbidden truths, and seeing the world for ‘what it is’ (Botto & Gottzén, 2023). However, having this ‘superior’ knowledge also distinguishes that individual from others who ‘lack’ it. The representation of this ‘us’ and ‘them’ mentality that is encouraged by the alt-right network is exacerbated in the filter bubble environment, allowing for easier ‘othering’ and assertive polarisation towards progressives.

One of Them

As each user operates on different information in their personalised filter bubble, the lack of mutual understanding that sprouts from that enhances the alt-rights ability to ‘other’ progressives, as they may appear ignorant or uninformed, encouraging the classification of them as ‘lesser’ than the alt-right groups (Holiday et al., 2004). This foundation can create a culture wherein arguments opposing the alt-right are more dismissible, as they appear ill-informed and below consideration (Holiday et al., 2004; Papacharissi & Trevey, 2023). The populist framing of ‘social justice warriors’ as threatening Western culture and restricting freedom of speech further encourages affective polarisation wherein animosity is perpetuated between alt-right and progressives. This is due to the increased homogeneity in online networks, which filter bubbles tend to induce and can result in increased isolation from other partisans (Iyengar et al., 2019).

Gradual Radicalisation

YouTube’s algorithmic ability to amplify filter bubbles and ‘other’ alternate beliefs and induce assertive polarisation can produce a compelling environment for user radicalisation, as illustrated in interviews and recounts such as that of ex-alt-righter Caleb Cain. In 2014, Mr Cain watched YouTube’s recommended self-help videos by men’s rights advocate Stefan Molyneux. While Mr Molyneux was not explicitly endorsing far-right ideologies, he acted as a “gateway to the far right” for the YouTube recommendations algorithm (Hosseinmardi et al., 2020, p. 1; Wurst, 2022). YouTube linked Mr Cain’s interests to right-leaning and viewership patterns with those of similar right-leaning users. As he gradually consumed extremer content, the algorithm was encouraged to feed him more and sustain his engagement. Over the next two years, Mr Cain watched increasing amounts of content from right-wing creators and even explicitly racist videos, despite having originally identified as a Liberal. While the radicalisation process can halt for some users as it eventually did for Mr Cain, others can become more engulfed and radicalised in their filter bubbles.

…”YouTube [is] a powerful recruiting tool for Neo-Nazis and the alt-right” (Byrant, 2020, p.1)

The Common Thread

Mr Cain is not a standalone case; YouTube has been identified as “… a powerful recruiting tool for Neo-Nazis and the alt-right” (Byrant, 2020, p.1). This is supported by Evan’s (2018) research, which found that 38% of fascists who credited the internet explicitly credited YouTube for their ‘red-pilling’. This is further illustrated by Brenton Tarrant, the shooter responsible for the Christchurch massacre in 2019, who previously donated to Mr Molyneux’s channel and, in his live streaming of the shooting, explicitly endorsed famous YouTuber ‘PewDiePie’. This direction of the audience towards YouTube suggests that he may have garnered some of his ideologies there and that YouTube can play a facilitative role in the radicalisation process (RCIACM, 2020). The shooter’s manifesto was further broadcast by popular white ethnonationalist YouTuber Joesph Cox to his 600,000 followers (Macklin, 2019). This action demonstrates the networked nature of the alt-right and how, in these filter bubbles, as alt-right political content creators inspire extremism amongst viewers, viewers can encourage extremity amongst creators, resulting in feedback loops of mutual radicalisation (Lewis, 2018). These theories are supported by research conducted into YouTube’s algorithms recommendation system, which suggests that although YouTube’s algorithm works to recommend content that aligns with users ‘ partisan beliefs, and that deeper in the recommendations trail is increasingly extremist content, with this trend being most evident with right-leaning users (Haroon et al., 2023; Haroon et al., 2022).

Conclusion

Users are shaped by the content they consume. The YouTube algorithm solidifies echo chambers, and the resulting filter bubble impedes users’ ability to empathise with subjects that have become ‘othered’, resulting in increased affective polarisation. This contributes to an environment where users are more susceptible to radicalisation, as Mr Cain and Mr Tarrant illustrated. While the distinguished radicalising force is often the alt-right community, the YouTube recommendations algorithm is responsible for steering users’ understanding of their political landscape and identity towards more extreme views through the interlinked alt-right network (Munger & Phillips, 2020). This network benefits from the amplification of the filter bubble phenomenon through the YouTube recommendations algorithm and its bias for controversial content, which contributes to an environment wherein the audience and alt-right influencers alike are encouraged to extremify their views, which raises the risk of political radicalisation.

References

Arguedas, A. R., Robertson, C., Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. (2022). Echo chambers, filter bubbles, and polarisation: a literature review. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-01/Echo_Chambers_Filter_Bubbles_and_Polarisation_A_Literature_Review.pdf

Botto, M., & Gottzén, L. (2023). Swallowing and spitting out the red pill: young men, vulnerability, and radicalization pathways in the manosphere. Journal of Gender Studies, 33(5), 596–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2023.2260318

Bryant, L. V. (2020). The YouTube algorithm and the Alt-Right filter bubble. Open Information Science, 4(1), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1515/opis-2020-0007

Covington, P., Adams, J., & Sargin, E. (2016). Deep Neural Networks for YouTube Recommendations. Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1145/2959100.2959190

Evans, R. (2018). From memes to infowards: How 75 Fascist activists were “red-pilled”. Bellingcat. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/americas/2018/10/11/memes-infowars-75-fascist-activists-red-pilled/

Goodrow, C. (2021, September 15). On YouTube’s recommendation system. YouTube Official Blog. https://blog.youtube/inside-youtube/on-youtubes-recommendation-system/

Haroon, M., Chhabra, A., Liu, X., Mohapatra, P., Shafiq, Z., & Wojcieszak, M. (2022). YouTube, the great radicalizer? Auditing and mitigating ideological biases in YouTube recommendations. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.10666

Haroon, M., Wojcieszak, M., Chhabra, A., Liu, X., Mohapatra, P., & Shafiq, Z. (2023). Auditing YouTube’s recommendation system for ideologically congenial, extreme, and problematic recommendations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS, 120(50). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2213020120

Holliday, A., Hyde, M., & Kullman, J. (2004). Otherization. Intercultural communication: An advanced resource book (1st ed, pp. 21-35). Routledge. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/detail.action?docID=182287

Hosseinmardi, H., Ghasemian, A., Clauset, A., Mobius, M., Rothschild, D. M., & Watts, D. J. (2021). Examining the consumption of radical content on YouTube. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS, 118(32), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2101967118

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Leung, D. K. K., & Lee, F. L. F. (2014). Cultivating an active online counter public: Examining usage and political impact of internet alternative media. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(3), 340-359.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214530787

Lewis, R. (2018). Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the reactionary right on YouTube. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/DS_Alternative_Influence.pdf

Macklin, G. (2019). The Christchurch Attacks: Livestream Terror in the Viral Video Age. CTCSENTINEL, 12(6), 18-29. https://ctc.westpoint.edu/christchurch-attacks-livestream-terror-viral-video-age/

Milano, S., Taddeo, M. & Floridi, L. (2020). Recommender systems and their ethical challenges. AI & Society, 35(6), 957-967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-00950-y

Munger, K., & Phillips, J. (2020). Right-Wing YouTube: A supply and demand perspective. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(1), 186-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220964767

Papacharissi, Z., & Trevey, M. T. (2018). Affective Publics and Windows of Opportunity: Social media and the potential for social change. In M. Graham (Ed.) The Routledge Companion to Media and Activism, (87-96). Routledge.

Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. Penguin.

Ribeiro, M. H., Ottoni, R., West, R., Almeida, V. A. F., & Meira, W. (2019). Auditing radicalization pathways on YouTube. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1908.08313

Roose, K. (2019). The making of a YouTube radical. The New York Times.

Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Attach on Christchurch Mosques on 15 March 2019 (2020). Ko tō tātou kāinga tēnei. https://christchurchattack.royalcommission.nz/the-report/part-2-context/harmful-behaviours-right-wing-extremism-and-radicalisation

Selvanathan, H. P., & Leidner, B. (2022). Normalization of the Alt-Right: How perceived prevalence and acceptability of the Alt-Right is linked to public attitudes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(6), 1594–1615. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211017633

The YouTube Team. (2019, January 25). Continuing our work to improve recommendations on YouTube. YouTube Official Blog. https://blog.youtube/news-and-events/continuing-our-work-to-improve/

Wurst, C. (2022). Bread and plots: Conspiracy theories and the rhetorical style of political influencer communities on YouTube. Media and Communication, 10(4), 213-223. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i4.5807

YouTube Creators. (2023, October 11). YouTube Partner Programme: How to make money on YouTube. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=om2WiDsHLso

Hi Shannon Kate, You’re right to ask; it is incredibly difficult to police these issues today. Predatory behaviour isn’t exclusive…