Abstract

This paper looks at how social media helped drive social change during the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement in Iran after Mahsa Amini’s death. When news of her death spread, platforms like Instagram, X (Twitter), and TikTok gave people a way to share their voices, show what was happening, and reach the world. This study aims to understand how online voices can challenge unfair rules and support women’s rights. Even though the protests did not lead to quick political changes, they made people around the world pay more attention. Governments placed sanctions, NGOs gave help, and more Iranians started to resist daily control. Although the Iranian government increased censorship and arrests, the movement still continues online. This case shows that even in difficult places, social media can give people the power to make their voices heard and to start long-term change.

Introduction

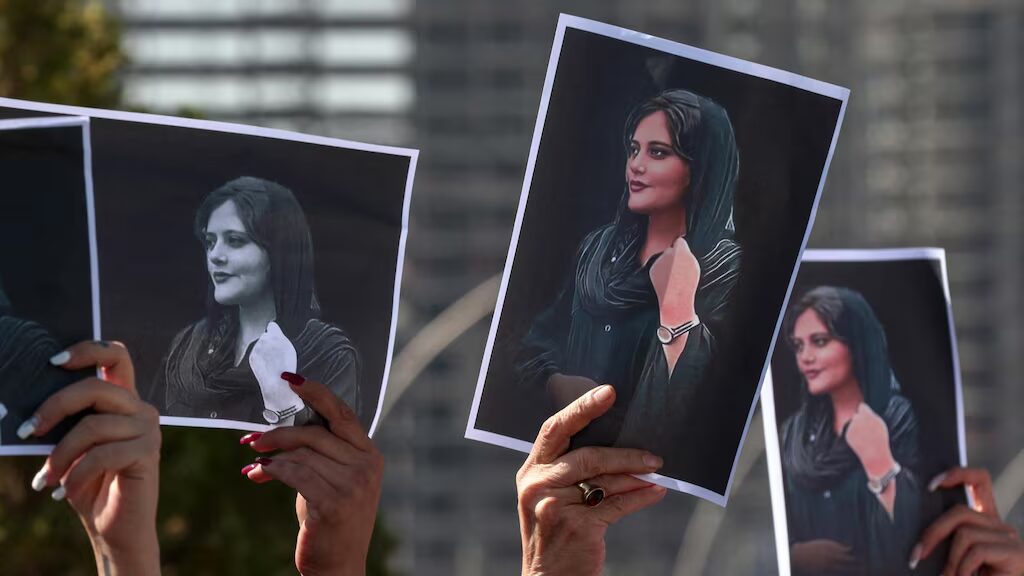

Social media can be a great way to drive people’s emotions and create opinions. Social platforms can influence social change. While in this case, it also had the effect of spreading rapidly to the world when Mahsa Amini in Iran was killed by the morality police due to the unregulated wearing of the hijab. In September 2022, 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who was visiting Tehran with her brother, was stopped and arrested by the moral police. According to reliable sources, she was tortured and ill-treated in the police car for resisting, resulting in unconsciousness. She died three days after being taken to the hospital (Amnesty International, 2023). This incident caused Amini’s death to resonate with the Kurdish movement that has been campaigning against the killing of Kurdish women for decades. So they chanted ‘Jin, Jiyan, Azadî ’ (Woman, Life, Freedom) at Mahsa Amini’s funeral in protest. Some women even removed their headscarves in protest. Security forces clashed with the crowd and news of the clashes spread quickly from the Internet (Pelham, 2024). Hence, the paper will be study on the role of social media in the ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ movement in Iran, illustrates how digital platforms can drive social change by exposing government oppression, empowering grassroots activism, and challenging traditional norms, ultimately leading to increased resistance and women’s awareness.

The Death of Mahsa Amini and the Spark of Protest

The protests soon erupted in other Iranian cities from Instagram and X (Twitter), two major social media platforms that used by Irian (Hassani, 2025 ; The Lancet, 2022). Later, participatory culter exists as the news was also spread to Tiktok and telegram sparking a global debate. People also started protesting in the streets in an attempt to get the government to respect women, and this action has managed to get the morality police to back off temporary (Pelham, 2024). Unfortunately, the Iranian government refused to acknowledge or respond to any questions regarding Mahsa Amini’s beating and the cause of her death. While the morality police did disappear for a short period, they eventually returned to the streets once the uproar had subsided. (Hafezi, 2023). Even more heartbreaking and controversial is that many women protesting on the streets were killed, sparking widespread outrage and condemnation.The Iranian government used unnecessary and excessive force to suppress protests after Mahsa Amini’s death, including sexually assaulting detainees. The months-long crackdown resulted in over 500 deaths and more than 22,000 arrests. Iranian officials refused to respond to these findings (Gambrell, 2024). This is why, after the incident, news articles with headlines like “The Failure of the Mahsa Amini Protest” started appearing one after another on Google. The roots of this slogan can be track back to women in the Kurdish National Liberation Movement in Turkey as part of the women’s rights movement (Askew, 2023). In 1998, during International Women’s Day, the Ideology of Women’s Liberation was introduced, emphasizing that women needed to break free not only from traditional social roles and the attitudes that reinforced them but also from the need for total autonomy and self-organization. Later, the Kurmanji Kurdish slogan “jîn, jîyan, azadî” (Women, Life, Freedom) started gaining popularity (Natakallam Blog, n.d.). Following the Mahsa Amini protests, this slogan was widely adopted in Iran, becoming a central rallying cry against religious extremism and in the fight for women’s freedom.

The Role of Social Media in the Movement

The key point here is that although this protest is often labeled as a “failed” protest, it has, in fact, successfully drawn worldwide attention through social media. As Rahman & Al-Azm (2023) stated, Iran is still overshadowed by the dominance of patriarchal culture and an ideology that defends gender inequality in all aspects of society. Although the majority of Kurdish people are Muslim, the main significance of removing the hijab is not the hijab itself, but the ‘compulsion’. Many Kurdish women are opposed to a system that turns religion into a tool of domination and oppresses women’s bodily autonomy by making it legally mandatory for all women to wear a headscarf (United Nation, 2024). Therefore, the fact that this resistance has spread across the world is already a significant step toward success. Despite the Iranian government has long exercised control over traditional media, but social media created a space where truth could be broadcast beyond borders. Platforms such as Instagram, X (Twitter), and TikTok became not only channels for real-time updates and eyewitness reports, but also virtual battlefields for resistance and solidarity. After this large-scale protest, there has been a noticeable rise in awareness among Iranian Kurdish women. We can see them gradually embracing and expressing themselves more freely on social media, whether it’s appearing in public without a headscarf or openly supporting feminism online. Under the government’s increasing oppression and authoritarian control, the courageous actions of Kurdish women in Iran remain truly admirable.

Global Solidarity and International Political Responses

Furthermore, as the incident gained international attention, people around the world start and continued to protest in solidarity. News reports show that on September 16, a year after the case, demonstrations were still taking place not only in Iran but also in cities like Paris, Brussels, and Berlin. One protester emphasized their determination by saying, “We just wanted to let everyone know that this is not going to finish,” meaning the movement will persist and their voices will not be silenced (Law et.al 2023). Other than that, numerous world leaders and international organizations have openly condemned the Iranian government’s response to the protests and have taken concrete steps to address the situation. For example, the European Union imposed sanctions on Iran’s Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, along with eight high-ranking individuals, including judges, lawmakers, and clerics believed to be connected to the violent crackdown on demonstrators (AP News, 2023). They also enforced travel bans and asset freezes on members of the squad involved in Mahsa Amini’s arrest, senior officials of the Revolutionary Guards, and Iran’s Interior Minister, Ahmad Vahidi (Reuters, 2022). Plus, according to The White House official website, the United States has taken action to support Iranian citizens by improving access to secure internet platforms and external digital services. In addition, the U.S. has held accountable key Iranian entities and individuals such as the Morality Police for their role in suppressing civil society through the use of violence (The White House, 2022). These responses, while mostly symbolic, added to the growing international pressure and signaled a broader shift in global attitudes toward gender-based oppression and authoritarian control.

NGO Support and the Power of Global Networks

In addition to governmental actions and public demonstrations, numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have played a pivotal role in supporting Iranian protesters and amplifying their voices on the international stage. Organasations such as Amnesty International has been at the forefront, meticulously documenting human rights violations and issuing urgent calls for global action against the Iranian authorities’ brutal crackdown (NCRI Women Committee, 2024). Beyond documentation, NGOs have facilitated solidarity movements and statements. For instance, a coalition of over 80 organizations, activists, academics, and lawyers released a joint statement urging the Iranian government to repeal discriminatory laws restricting women’s freedoms (Parsa, 2023). Additionally, international women’s organizations have actively supported Iran’s protest movement, condemning the harsh government crackdown and advocating for the expansion of women’s rights (Katulis, 2025). Additionally, there are also NGOs take part in beyond statements of solidarity by offering tangible support to Iranian women activists. Organizations like United for Iran and the Center for Human Rights in Iran have created emergency funds to assist protesters facing legal consequences, loss of income, or physical and psychological trauma (United4Iran, n.d.; Center for Human Rights in Iran, n.d.). These funds have been used to provide legal defense, mental health services, and even shelter for women under threat. The collective efforts by NGOs have not only shed light on the oppressive actions of the Iranian regime but have also fostered a global network of support, empowering Iranian activists and sustaining the momentum of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement. Social media has played a critical role in amplifying these efforts, enabling NGOs to rapidly disseminate information, coordinate global solidarity campaigns, and connect with activists on the ground. Through platforms like Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube, the world has been able to witness the protests firsthand and respond with meaningful action (YouTube, n.d.; X, n.d.).

Social Changes Triggered by the Movement

As most of the above relates to the role social media played during the protest, we will subsequently address the social change in this case due to social media. After successful people’s protests and the murder of Mahsa Amini, common usage of social media has ushered in various significant cases of social change, both in Iran and globally. To begin with, it broke the walls of censorship within Iran, allowing citizens, especially women, to reclaim their voice and document state brutality in real time. This exposure forced the Iranian regime to make a temporary withdrawal, showing how online exposure forces authoritarian regimes to back down, even if momentarily. Beyond Iran’s borders, the protests driven by viral content witnessed increased global solidarity. People worldwide went onto the streets in protests, converting one a national movement into an international explosion seeking the rights and freedom of women. The shared vocabulary of images and hashtags formed a solidarity that was above politics and culture. Organizationally, social media mobilization forced global governments and NGOs to respond. Sanctions were slapped, access to the internet widened, and dollars were spent in order to expand the rights of women (United4Iran, n.d.; Center for Human Rights in Iran, n.d.). These are tangible fruits of a revolution spawned and fostered on the internet. But not all had improved for the better. The regime struck back with greater cyber-surveillance and repression. But even in repression, the movement continues to bear witness as the power dynamic has been changed with social media, with ordinary citizens having a platform where they can force global attention and response. And from this, it is clear that even social media protests can’t always lead to wholly positive change. Still, it is certain that in most instances, social media is the sole medium which can raise the issue and seek assistance.

Conclusion

Conclusion, the protests that followed the killing of Mahsa Amini were not only domestic protests but an international call for justice, women’s rights, and human dignity. Notwithstanding the Iranian regime’s efforts to stifle these voices by using brutal repression, social media was central to the transmission of the truth, raising awareness, and mobilizing people across borders. Social media platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube became resistance tools whereby citizens were able to record state brutality, facilitate diaspora communities to mobilize solidarity protests, and compel the global community, including global leaders, NGOs, and human rights groups to respond. These online platforms not only kept the memory of Mahsa Amini alive but turned her into an international symbol of resistance. The social change enflamed by the movement was wildly varying from economic sanctions and diplomatic pressure on the regime in Iran to strengthening feminist networks and civil society groups. More significantly, it demonstrated how ordinary citizens, not to mention women, could resist hard-wired patriarch regimes by the power of their voice and connectivity. While social media activism in itself will not topple authoritarianism overnight, it most definitely gives access to international discourse, policy change, and support networks beyond previous reach. The “Women, Life, Freedom” movement is an example of how online activism, although not overnight, has already begun to shift opinion, disrupt oppressive structures, and organize global solidarity. It reminds us that real social change is frequently difficult and incremental, but even in opposition, the hundreds of thousands of voices that echoed through electronic media have the potential to initiate a struggle that will smolder for decades to come.

References

Amnesty International: Two years after “woman life freedom” uprising, impunity for crimes Reigns Supreme. NCRI Women Committee. (2024, September 16). https://wncri.org/2024/09/14/amnesty-international-report-2/

AP News. (2023, March 20). EU targets top Iran body, 8 officials over rights abuses. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/eu-iran-sanctions-protests-morality-28c12c33f3e43d675ca25c847f5a9558

Askew, J. (n.d.). Words have power: The origins of “woman, life, freedom.” euronews. https://www.euronews.com/2023/01/11/words-have-power-what-are-the-origins-of-woman-life-freedom-iran-protest-chants

Bell, M. (2024, March 21). The Kurdish roots of “Woman, life, freedom.” NaTakallam. https://natakallam.com/blog/the-kurdish-roots-of-woman-life-freedom/

Center for Human Rights in Iran. (2025, January 31). https://iranhumanrights.org/

Gambrell, J. (2024, March 8). Iran is responsible for the “physical violence” that killed Mahsa Amini in 2022, UN probe finds. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/iran-is-responsible-for-the-physical-violence-that-killed-mahsa-amini-in-2022-un-probe-finds

Hassani, S. T. (2024, March 27). Iran’s Instagram crackdown is jeopardising women’s livelihoods. Bourse & Bazaar Foundation. https://www.bourseandbazaar.org/articles/2024/3/12/irans-instagram-crackdown-is-jeopardising-womens-livelihoods#:~:text=Instagram%20is%20one%20of%20the,hijab’’%20have%20economic%20consequences

Horton, R. (2022). Offline: Women, life, freedom—and Twitter. The Lancet, 400(10358), 1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01879-7

Katulis, B., Salem, P., & Vatanka, A. (2025, April 2). How international women’s organizations are supporting Iran’s protest movement. Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/how-international-womens-organizations-are-supporting-irans-protest-movement

Law, H., Mando, N., Chen, H., Akbarzai, S., & Tawfeeq, M. (2023, September 17). Protests erupt in Iran, one year after Mahsa Amini’s death. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/09/17/middleeast/iran-protests-mahsa-amini-anniversary-intl-hnk/index.html

National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). Statement by president Biden on the violent crackdown in Iran | The White House. National Archives and Records Administration. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/10/03/statement-by-president-biden-on-the-violent-crackdown-in-iran/

Parsa, F. (2023, September 19). Mahsa Amini’s legacy: A new movement for Iranian women | carnegie endowment for international peace. Sasa. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/2023/09/mahsa-aminis-legacy-a-new-movement-for-iranian-women?lang=en

Pelham, L. (2024, March 8). Mahsa Amini: Iran responsible for “physical violence” leading to death, Un says. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-68511112

Rahman, M. M., & Al-Azm, A. (n.d.). Social Change in the Gulf Region : Multidisciplinary Perspectives (1st ed., Vol. 8, Ser. Gulf Studies, pp. 1–14). essay, Springer.

Reuters. (2022, November 15). EU sanctions 29 Iranians, three organisations over crackdown on protests. euronews. https://www.euronews.com/2022/11/15/eu-diplomacy

United Nations. (n.d.). Iran: UN experts call for strict new hijab law to be repealed | UN news. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/12/1158171

What happened to Mahsa/Zhina Amini?. Amnesty International. (2023, September 15). https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/09/what-happened-to-mahsa-zhina-amini/

What has changed in Iran one year since Mahsa Amini protests erupted? | Reuters. (n.d.-a). https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/what-has-changed-iran-one-year-since-mahsa-amini-protests-erupted-2023-09-11/

Who we are. United4Iran. (n.d.). https://united4iran.org/about/

X. (n.d.-b). https://x.com/search?q=%23MahsaAmini&src=typeahead_click&f=top

YouTube. (n.d.). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=%23mahsaamini

Hi Shannon Kate, You’re right to ask; it is incredibly difficult to police these issues today. Predatory behaviour isn’t exclusive…