Abstract

By first establishing a cynical political climate, this paper highlights how Donald Trump was able to secure votes from the growing disgruntled alt-right public. This paper also utilizes successful movement from Tahrir Square and MyBarackObama to showcase social media’s power to mobilize publics for social change. The analysis show that attention commodity and decentralized processes bypasses issues of audience appropriateness and context, allowing toxic rhetorics to be sustained, proliferate and gravitate to one political representative: Donald Trump.

Introduction

Donald Trump is a controversial figure spreading racist, sexist and xenophobic ideologies and policies, particularly in the Twitter sphere (Vlatkovic, 2018) and has a track record of fear mongering, outlandish claims and lies about his successful businesses (Durham, 2018), yet he was elected in the 2016 elections and again in the 2024 elections (CNN Politics, 2025). Drawing on previous political movements such as the Tahrir Square protests and previous preceding campaigns by the Obama administration, this paper argues that Donald Trump utilized social media affordances, especially decentralized processes and attention commodity to tap into, secure votes and mobilize publics from the growing disgruntled alt-right community and media, and publics within modern cynical political climate.

Collective Public, Politics and Social Change

Before we analyze Donald’s Trump utilization of social media it is essential to examine the relationship between collective publics, politics and social change. The collective public has roots from sociological, political and cultural studies and theories summarized as: an imagined community or civically engaged group participating in collective behavior to articulate, exchange and debate meanings and discourse and to question political power (Ojala & Ripatti-Torniainen, 2023). This includes everyday talk and public expressions of personal opinions and attitudes (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). A ‘public’ can refer to a local or broader collection of people like members of a nation (Boyd, 2010). The protest in Tahrir Square in Cairo is an example of collective public and collective action. Students, workers and citizens demanded political freedom, decent working conditions and basic humans rights against the Mubarak regime (Hands, 2014).

However, while Tahrir Square was the result of intense oppression, not all political matters can mobilize collective publics for action. Recent studies reveal the climate of modern politics has left citizens cynical (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). Western politics is a system of democratic representation, but is paradoxical as political representatives and candidates cannot accommodate for every public’s needs, wants and desires of political outcome, thus cynicism and skepticism amongst publics accumulate leading to an aversion of participation towards voting and community involvement (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). Cynicism and skepticism is amplified by global and political instabilities such as financial crises and terrorism, leaving citizens further disillusioned, disappointed and a feeling of lost agency (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). Publics are desperate for an easy-fix and a way to restore agency within constituent policies and are looking for authentic and relatable candidates, thus are vulnerable to affectively charged claims and emotionally invoking campaigns (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). This is important to acknowledge as defining the current political climate is essential to analyzing how Donald Trump and his administration utilized social media to secure votes on the 2016 election.

Finally, collective public and collective action such as protests bring attention to certain issues (Freelon, Marwick & Kreiss, 2020) and forces governments to fulfill their roles as representatives to address those issues, allowing opportunity for social change (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018).

Communication Technology Affordances

The advancement of communication technology has changed the way people come together, participate in discourse and political debates, and are exposed to and mobilise for movements and collective action (Ojala & Ripatti-Torniainen, 2023), often with greater speed and size than their traditional media counterparts (Gonzalez-Bailon, 2014). The second stage of development of the internet or ‘Web 2.0’ allow social media sites, like Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, affordances for users like the ability to generate their own content, interact, discuss and share with other people online including photos, audio and videos (Lee et al., 2008; Shange et al., 2011; Arya & Mishra, 2012). Social media also enables two-way communication anywhere anytime, form online communities (Shang et al., 2011) and connects people with similar interests (Lee et al., 2008). These virtual communities transcend limitations of time, mobility and distance, allowing users global communication and constant connection (Delanty, 2018).

This constant connection affords users persistent contact with others in their connected networks and pervasive awareness of the interests of individuals they are connected to (Hampton, 2015). This can both be beneficial as this increases access to diverse points of view and/or harmful as social media algorithms may push similar content associated with social ties creating echo chambers and filter bubbles (Hampton, 2015; Hampton & Wellman, 2018). Algorithmic features such as RSS track discussions, conversations, topics, articles and newsgroups to generate a self-updating feed that is tailored to the user (Lee et al., 2008). Knowledge is also collective and collaborative with the use of social tagging like hashtags, organizing references and directing people to topics and movements (Arya & Mishra, 2012).

Networked Publics and Affordances

Boyd (2010) describes this relationship between social media and publics as ‘networked publics’ as social network sites connect a large mass of people and provide the space for interaction and information. Profile creation, post and comment features allow publics to craft a virtual representation of themselves and interact with each other (Boyd, 2010). Friend lists can reflect participant’s social and political standing based on who they surround themselves with (Boyd, 2010). Boyd (2010) also describes these structural affordances technology provides as persistence, replicability, scalability and searchability. Persistence refers to social media’s ability to record and maintain digital footprints, information in public spaces is hard to eradicate (Boyd, 2010). Replicability is the ease in reproduction of news and information, also potentially increasing their circulation, however, can be taken out of context with each replication (Boyd, 2010). Scalability, refers to social media’s ability to enable wider distribution and visibility (Boyd, 2010). Lastly, metadata organize online content allowing search engines to locate persisting records and information, this is referred to as searchability (Boyd, 2010).

Boyd (2010) also illuminates the pitfalls of networked publics categorizing them as invisible audiences, collapsed context and the blurring of private and public. Because online communities are imagined communities, unlike face-to-face interactions, users cannot capture the full scope of their audiences, so it is difficult to determine socially appropriate content or relatability, therefore context is important when addressing an audience (Boyd, 2010). Even when context and audience align, it is not guaranteed people’s own cultural and social context align with the content or each other (Boyd, 2010). Lastly, because social media occurs in public spaces privacy is disrupted and challenged, especially when something that is meant to be private is publicized (Boyd, 2010).

Networked Publics, Social Media and Movements

Technological and networked publics affordances do not determine people’s behaviors but alters the environment in which people communicate in (Boyd, 2010). Digital technology has turned political engagement into a decentralized process, where there is no authority figure processing information and overseeing strategies (Gonzalez-Bailon, 2014). Diamond (2010) describes social media as tools for liberation, allowing citizens to “expose wrong doing, express opinions, mobilize protests, monitor elections, scrutinize governments” (as cited in Poell, 2014, p.189). The internet organizes publics into networks that share political discussion without coercion or incentives (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018), allowing flexible forms of collective action uninhibited by resource-rich hierarchies (Papacharissi, & Trevey, 2018) and organizations (Gonzalez-Bailon, 2014). Communication technology is used to enhance global visibility of movements by coordinating actions and targeting online networks with their messages to reach larger audiences and involve more participants (Gonzalez-Bailon, 2014).

This can be seen again with the protests in Tahrir Square against Egyptian authoritarian police state. Facebook was utilized to combat state-controlled media, allowing a platform for expression of support, coordination of activities and mobilizing of movements through user created posts, events and pages that invited mutual feeling individuals to participate (Salem, 2014). Blogging was also an essential tool for the movement, empowering activists to connect and discuss with individuals with differing backgrounds and beliefs to act together (Salem, 2014). Bloggers publicized police torture on citizens, leading as a main factor of the mass mobilization (Salem, 2014). Another notable use of blogging was the ‘We are the 99%’ in Tumblr for the Occupy Wall Street movements in Europe, allowing protesters to voice their frustrations; inequality of medical care, pollution and wages between the 99% of hard-working citizens victimized by unfair political economic establishment and the wealthy ‘1%’, garnering attention and support world-wide (Porta & Mattoni, 2014). The organizing power of hashtags enabled people to follow conversations and topics (Nahon, 2015) on Twitter such as #Jan25, which follows the brutal death of Khaled Said at the hands of Egyptian police, and was instrumental in the lead up to the Tahrir Square protests (Salem, 2014). The wide reach and persistence these social media platforms facilitate can be attributed to each platform’s capacity to distribute information through likes, shares, comments, replying, tagging, mentions and re-tweets (Gerbaudo, 2014). These combined eventually led to the toppling and resignation of President Hosni Mubarak and his regime (Salem, 2014).

While a decentralized process is beneficial for the mobilization of movements, it can be a double-edged sword. The lack of a governing body can encourage toxic communities to proliferate, Reddit serves as an example (Massanari, 2017). Affordances within Reddit include anonymity, upvoting/downvoting, karma points and Reddit administration demonstrate extremely hands off approach (Massanari, 2017). Essentially, anything goes without repercussion, users are able to participate with controversial content except the sharing of private information, explicit images of minors, spam and hacking (Massanari, 2017). Reddit’s algorithm is influenced by upvoted content, best-voted appear on default home pages and earn karma points marking individuals as a valuable contributor and encouraging the spread of material to other subreddits in order to earn more karma (Massanari, 2017). Even if content is considered regressive by mainstream standards, as long as there are substantial users mirroring similar beliefs, content will continue to spread and grow (Massanari, 2017).

It is also important to be aware that while social media are independent from governments and organizations, social media is run by corporations and cannot be a fully liberating tool (Poell, 2014). Corporations collect metadata for targeted advertising and monetization, thus requires real names and information to maximise profitability (Poell, 2014). This clashes with activist pseudonym accounts and lead to the deactivation of movement pages such as the ‘We are all Khaleid Said’ Facebook page (Poell, 2014). To lower costs of monitoring user-generated material corporations allow users to report each other for terms of service violations and offensive material, giving state agents and regime supporters opportunity to stifle activist movements (Poell, 2014). Furthermore, there are issues with privacy concerns following the scandal of Donald Trump’s employment of Cambridge Analytica, harvesting metadata without consent (Cadwalladr & Graham-Harrison, 2018). This included data affiliated with economic, political and social roles of Facebook users (Trottier & Fuchs, 2014) to deploy demographically-targeted advertisements to influence voting preferences in the 2016 presidential election (Hinds et al., 2020). Lastly, in networked publics where users are drowned in information, attention becomes a commodity (Boyd, 2010), thus social media sites employ algorithms that prioritize content that users are more likely to interact and agree with (Nahon, 2015), which also aids in a corporation’s goal to capture as many users as possible (Poell, 2014).

Public elites can also utilize social media to communicate with mass publics their own campaigns and goals (Wright, Graham & Jackson, 2015). The most successful example of this is Barrack Obama’s presidential campaign (Chadwick et al., 2015). In addition to traditional media, Obama incorporated social media tools (Chadwick et al., 2015), creating MyBarackObama.com (MyBO) (Aaker et al., 2010). MyBO transformed users into activists, allowing users to create their own profile, connect and chat with other users, engage with political topics, find or plan offline events and raise funds (Aaker et al., 2010). The Obama campaign also used YouTube as a persistent archival resource and mode of virality (Chadwick et al., 2015). The use of social media gave Obama an edge as research indicates social media is a more trusted form of source in opinions about politicians, as users can draw on and influence other users’ opinions of political candidates (Vlatkovic, 2018). This represents a shift in politics to the splitting of political content across different types of media for different types of audiences as campaign teams can no longer assume they will reach their target audiences en masse (Chadwick et al., 2015).

Donald Trump, Twitter and the Alt-right

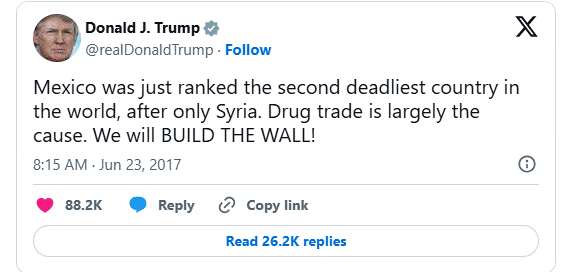

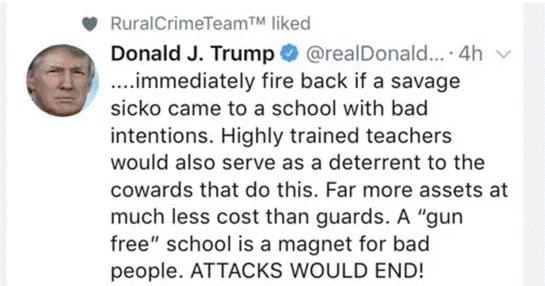

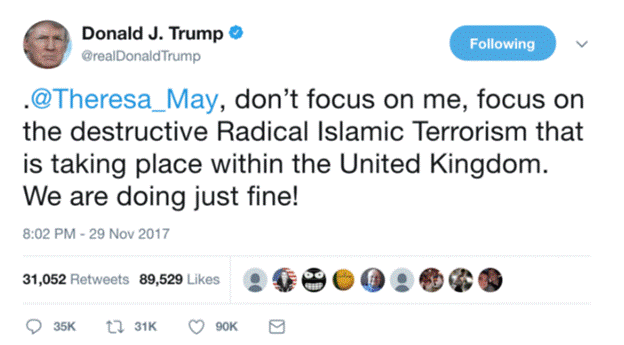

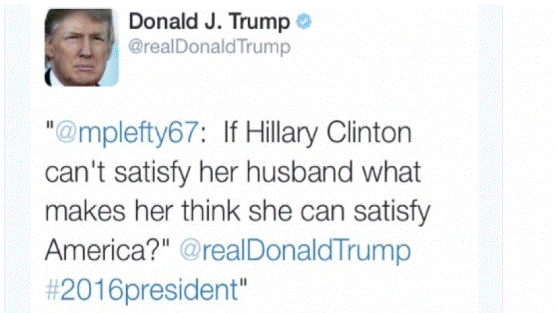

Similarly, Donald Trump used Twitter to communicate with the collective public during his campaign (Vlatkovic, 2018). As mentioned before, attention is a commodity (Boyd, 2010), humans have limited capacity for storing information (Vlatkovic, 2018). Twitter negotiates this demand limiting posts to 140 characters, delivering swift, focused and easy to consume information amongst the saturation of digital spaces (Vlatkovic, 2018). Notifications also keep users connected and regularly engaged (Kellner, 2018). This allowed Trump to maintain a persistent presence in social media, attacking media critics who “misrepresent” him, to brag (Kellner, 2018) and to regularly interact with the public in real time (Vlatkovic, 2018). Twitter also enabled politicians to bypass the press to speak directly to voters, gaining authenticity (Vlatkovic, 2018) which is important to combatting the modern cynical political climate (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). The number of followers also increased Trump’s political scalability, he was followed by 30 million people compared to Hillary Clinton’s 15 million, allowing him to reach a wider audience (Vlatkovic, 2018). Interestingly, contrary to the careful consideration of audiences and appropriateness to content and the dangers of collapsed contexts (Boyd, 2010), Trump thrived by throwing this all out the window, favoring the undivided attention that controversy brings while simultaneously engaging with users on topics important to him (Vlatkovic, 2018). Such topics included the mass deportation of Mexican immigrants, banning of Muslims on entering the U.S. and sexual degradation on his political rival.

(Retrieved from https://woodstockwhisperer.info/2019/06/10/president-trump-wall/)

(Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-north-west-wales-43212577)

(Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Donald-Trump-tweet-November-29-2017-Several-weeks-after-this-incident-Twitter_fig3_334544421)

(Retrieved from https://secure.avaaz.org/campaign/en/twitter_ban_trump_21/)

This is coherent with Papacharissi & Trevey (2018) statement that the public are vulnerable to affectively charged claims and emotionally invoking campaigns, even if in this case it’s untrue and hateful. Furthermore, these narratives driven by fear, inuendo and lies were sustained by enduring right-wing beliefs, resistance against science (Durham, 2018) and racist media, and propaganda pushed by alt-right digital networks media such as Fox News (Altheide, 2022), websites such as Breitbart News and social media such as 4chan (Wendling, 2018, p. 2 & 51). Breitbart News challenged left-wing control of media narratives, intentionally feeding mainstream journalists fake stories that would then air on Fox News and circulate in media platforms, which ironically or unironically fueled Trump’s accusation of ‘fake news’ towards reports that did not favor him, delegitimizing the press (Durham, 2018; Vlatkovic, 2018). This form of fake news distribution is also a tactic employed by 4chan known as ‘trolling’ and comes in forms such as memes, hoaxes, twitter campaigns of bullying and defamation and spread of misinformation to incite reactions and aggravate liberals and the mainstream (Wendling, 2018, p. 10). Like Reddit, 4chan is also divided into subsections, the alt-right reside in “Politically Incorrect” (Wendling, 2018, p. 52). Members of these section engage unchecked in racist, sexist and xenophobic exchange of ideas, usually triggered by an aversion to political correctness as they struggle to navigate society’s awareness of privilege, safe spaces and sexual politics (Wendling, 2018, p. 8). Most of these members are a generational backlash of young men threatened by the progress of feminism, ethnic minorities and the dangers of Islamic terrorism (Wendling, 2018, p. 7). These men desire the restoration of racially motivated hierarchy and gender roles (Wendling, 2018, p. 7). These are topics that underline Trump’s presidential rhetorics, thus resonate in voters to look to Trump for an easy-fix and a way to restore agency (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018) combatting immigration, left-wing narratives and restoration of traditional roles.

Conclusion

In this paper I have identified that social media sites give users and political bodies affordances of social change under umbrellas of: mobilization of collective networks, decentralized processes and attention commodity. Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr and YouTube amplify the scalability, mobility and organization power of collective publics and collective action (Ojala, & Ripatti-Torniaien, 2023) like Tahrir Square and play a huge role in campaigns demonstrated by the Obama and Trump administrations, providing a platform to interact with each other, distribute information and form networked communities (Shang et al., 2011). The most effective examples provided shared features of decentralized processes and attention commodity, the absence of a governing body and easily consumable content made movements and candidates feel unfiltered and authentic (Vlatkovic, 2018), which is valuable in today’s cynical political climate (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). Furthermore, Trump utilized attention commodity better than his political rivals, bypassing issues of audience and contexts, controversy was free attention that allowed his presence to persist and stay relevant and he was getting a lot of it (Vlatkovic, 2018). Taking into consideration Trump’s regressive attitudes and the support and mobilization of his connected networks of desperate disgruntled alt-right, I would like to propose that Trump’s influence on social change can be better categorized as social regression.

References

Aaker, J., Smith A., Adler, C., Heath, C. & Ariely, D. (2010). Yes we can! How Obama won with

social media. In J. Aaker, A. Smith, C. Adler, C. Heath & D. Ariely (Eds.), The

Dragonfly Effect : Quick, Effective, and Powerful Ways to Use Social Media to Drive

Social Change (pp. 34-39). https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=589081&ppg=64

Altheide, D. (2022). Trump and the Mediated Politics of Fear. In D. L. Altheide (Ed.), Gonzo

governance (1st ed., pp. 16-31). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003330837

Arya, H. B. & Mishra J. K. (2012). Oh! Web 2.0, Virtual Reference Service 2.0, Tools &

Techniques (II). Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning 6(1),

28-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2012.660878

Boyd, D. (2010). Social Network Sites as Networked Publics. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A

Networked Self (1st ed., pp. 39-58). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203876527-8/social-network-sites-networked-publics-affordances-dynamics-implications-danah-boyd

Cadwalladr, C. & Graham-Harrison, E. (2018, March, 18). Revealed: 50 million Facebook

profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election

Chadwick, A., Dennis J. & Smith, A. P. (2015). Politics in the age of hybrid media. In A. Bruns,

G. Enli, E. Skogerbo & A. O. Larsson, C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge

Companion to Social Media and Politics (1st ed., pp. 7-22).

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716299

CNN Politics. (2025, April, 7). CNN Politics. https://edition.cnn.com/election/2024/results/president?election-data-id=2024-PG&election-painting-mode=projection-with-lead&filter-key-races=false&filter-flipped=false&filter-remaining=false

Delanty, G. (2018). Virtual Community. In G. Delanty (3rd Ed.), Community (3rd ed., pp. 200-

224). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/mono/10.4324/9781315158259-10/virtual-community-gerard-delanty

Duraham, F. (2018). The origins of Trump’s “alternative reality”. In R. E. Gutsche Jr. (Ed.), The

Trump Presidency, Journalism, and Democracy, (pp. 181-191). Taylor & Francis

Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=5228978&ppg=52#ppg=32

Freelon, D., Marwick, A. & Kreiss, D. (2020). False equivalencies: Online activism from left to

right. Science 369(6508), 1197-1201. DOI: 10.1126/science.abb2428

Gerbaudo, P. (2014). Populism 2.0. In D. Trottier & C. Fuchs (Eds.), Social Media, Politics and

the State : Protests, Revolutions, Riots, Crime and Policing in the Age of Facebook,

Twitter and YouTube (pp. 67-87). Taylor & Francis Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=1744193&ppg=219

Gonzalez-Bailon, S. (2014). Online Social Networks and Bottom-up Politics. In M. Graham (Ed.

et al). Society and the internet: how networks of information and communication are

changing our lives (pp. 209-222). Oxford University Press. https://curtin.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/delivery/61CUR_INST/12181940870001951

Hampton, K. N. (2015). Persistent and Pervasive Community: New Communication

Technologies and the Future of Community. American Behavioral Scientist 60(1),

101-124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764215601714

Hampton, K. N. & Wellman, B. (2018). Lost and Saved . . . Again: The Moral Panic about the

Loss of Community Takes Hold of Social Media. Contemporary Sociology 47(6),

643-651. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26585966

Hands, J. (2014). General Intellect or Collective Idiocy? Digital Mobs and Social Media

Mobilization. Popular Communication 12(4), 237-250.

DOI:10.1080/15405702.2014.960570

Hinds, J., Williams E. J. & Joinson A. N. (2020). “It wouldn’t happen to me”: Privacy concerns

and perspectives following the Cambridge Analytica scandal. International

Journal of Human-Computer Studies 143, 1-14.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102498

Kellner, D. (2018). Donald Trump and the war on media. In R. E. Gutsche Jr. (Ed.), The Trump

Presidency, Journalism, and Democracy, (pp. 19-38). Taylor & Francis Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=5228978&ppg=52#ppg=32

Lee, M. J. W., Miller, C. & Newnham L. (2008). RSS and content syndication in higher

education: subscribing to a new model of teaching and learning. Educational

Media International 45(4), 311-322. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523980802573255

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance,

and culture support toxic technocultures. New media & society 19(3), 329-346.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Nahon, K. (2015). Where there is social media there is politics. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo

& A. O. Larsson, C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Social Media

and Politics (1st ed., pp. 39-55). Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716299

Ojala, M. & Ripatti-Torniainen (2024). Where is the public of ‘networked publics’? A critical

analysis of the theoretical limitations of online publics research. European Journal

of Communication 39(2), 145-160. DOI: 10.1177/02673231231210207

Papacharissi, Z & Trevey, M. T. (2018). Affective publics and windows of opportunity. In G.

Meikle (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Media and Activism (1st ed., pp. 87-

96). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315475059-9/affective-publics-windows-opportunity-zizi-papacharissi-meggan-taylor-trevey?context=ubx&refId=a74432dd-6fb1-416b-a74e-9f55f2c2d1e9

Poell, T. (2014). Social media activism and state censorship. In D. Trottier & C. Fuchs (Eds.),

Social Media, Politics and the State : Protests, Revolutions, Riots, Crime and

Policing in the Age of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube (pp. 189-206). Taylor &

Francis Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=1744193&ppg=219

Porta, D. & Mattoni, A. (2014). Social networking sites in pro-democracy and anti-austerity

protests. In D. Trottier & C. Fuchs (Eds.), Social Media, Politics and the State :

Protests, Revolutions, Riots, Crime and Policing in the Age of Facebook, Twitter

and YouTube (pp. 39-63). Taylor & Francis Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=1744193&ppg=219

Salem, S. (2014). Creating spaces for dissent. In D. Trottier & C. Fuchs (Eds.), Social Media,

Politics and the State : Protests, Revolutions, Riots, Crime and Policing in the Age

of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube (pp. 171-188). Taylor & Francis Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=1744193&ppg=219

Shang, S. S. C., Li, E. Y., Wu, Y. & Hou, O. C. L. (2011). Understanding Web 2.0 service

models: A knowledge-creating perspective. Information & Management 48(4-5),

178-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2011.01.005

Trottier, D. & Fuchs, C. (2014). Theorising social media, politics and the state. In D. Trottier &

C. Fuchs (Eds.), Social Media, Politics and the State : Protests, Revolutions,

Riots, Crime and Policing in the Age of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube (pp. 3-

39). Taylor & Francis Group. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=1744193&ppg=219

Vlatkovic, S. (2018). New Communication Forms and Political Framing: Twitter in Donald

Trump’s Presidential Campaign. AM Journal of Art and Media Studies (16),

123−134. https://doi.org/10.25038/am.v0i16.259

Wendling, M. (2018). Alt-Right : From 4chan to the White House. Pluto Press.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=5391114&ppg=8

Wright, S. Graham T. & Jackson D. (2015). Third Space, Social Media, and Everyday Political

Talk. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo & A. O. Larsson, C. Christensen (Eds.),

The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics (1st ed., pp. 74-88).

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716299

Hi Shannon Kate, You’re right to ask; it is incredibly difficult to police these issues today. Predatory behaviour isn’t exclusive…