Abstract:

As social media becomes more and more a part of everyday life for kids and teens, there’s growing concern about what all this online time is doing to their mental health, sense of identity, and privacy. Apps like TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat give young people fun ways to be creative and stay connected with friends, but they also open the door to some pretty serious problems—like constant pressure to perform, sketchy algorithms, and not-so-great safety measures. Even though there are supposed to be age limits, a lot of kids are getting on these platforms way before they’re legally allowed, which raises some big questions about how easy it is to slip through the cracks and how little oversight there really is.

This paper argues that social media has a huge impact on how young people figure out and present who they are, but the way these platforms are built tends to put making money and keeping people hooked ahead of actually protecting users. By looking at how digital identities are shaped, where platforms fall short, what ethical data practices should look like, and how people are fighting for better protections, the paper shows the constant push and pull between giving kids freedom and leaving them vulnerable. Using research, recent studies, and political discussions, it becomes clear that while more people are waking up to these problems, real policy changes and safer, more ethical designs are still missing. Until there’s stronger regulation, more youth involvement, and a serious focus on protecting kids, social media is going to keep putting the next generation at risk.

Introduction:

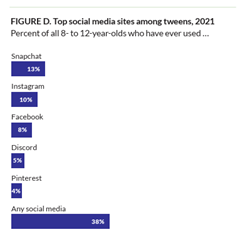

It is no surprise that today’s youth are growing up online. A survey by the Pew Research Center, showed that 95% of U.S. teens now have access to a smartphone (Vogels, 2022). It’s becoming a part of daily life for nearly every teenager. Social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and YouTube are now more than just entertainment, they are key spaces where young people can connect and express themselves and continue to figure out who they are. A 2021 report by Common Sense Media found that nearly 40% of children aged 8 to 12 reported using social media, as shown in Figure 1, despite most platforms setting the minimum age for users at 13 (Rideout, Peebles, Mann, & Robb, 2021). This big difference between age restrictions and real-world use raises urgent questions about youth safety and their identity development and regulation online.

Figure 1: Top social media platforms used by U.S. tweens (ages 8-12) in 2021. (Source: Ridout, Peebles, Mann, & Robb, 2021, p.5)

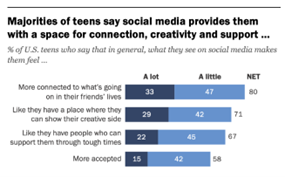

Noone will deny that these platforms can offer creative opportunities and social connection. Figure 2 shows that when U.S. teens between 13 and 17 were asked in a 2022 survey, as high as 70% said that social media gives them a space to express their creative side and 80% said they felt more connected to what is going on in their friends lives (Pew Research Centre, 2022). However, social media platforms do also present some serious risks. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2021) highlights growing concerns about anxiety, depression, and cyberbullying, among young users, while other scholars have pointed to risks including performance pressure, unrealistic beauty standards and data exploitation (James et al., 2019).

Figure 2: Percent of U.S. teens who say social media helps them feel more connected, creative and supported. Source: Pew Research Center (2022).

These challenges are further compounded by the fact that most platforms are not designed with youth safety or well-being in mind. Critics argue that many social media companies optimise their platforms for engagement and profitability, often at the expense of ethical design and meaningful regulation (Kidron, 2023). Given that many underage users are active on platforms despite age restrictions, weak age verification systems, combined with engagement driven algorithms, and limited protective measures, leave young users increasingly vulnerable to manipulation, exploitation, and psychological harm (American Psychological Association, 2023).

This paper argues that although social media plays a major role in shaping how current and future young people explore and perform their identities, it is fundamentally flawed in how it treats underage users. A mix of ethical concerns, design failures, and weak regulation have created a digital environment where profit is prioritised over protection. By examining the dynamics of identity development, platform shortcomings, data ethics, and current advocacy efforts, this paper highlights the urgent need for reform. Unless these platforms start being built with young users in mind from design to policy, then social media will remain a space where opportunity and harm exist side by side for the next generation.

Digital Identity and Underage Users

As we have established, social media plays a powerful role in how children and teens can explore and express their identities. As Danah Boyd (2014) explains, online platforms offer young people critical spaces to “hangout”, test boundaries, and perform identity in front of their peers. Platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat encourage users to curate their online selves through photos, videos, bios, and shared content, practices that reflect what Papacharissi (2011) calls the performance of a “networked self”. For young users, this becomes a key space to test out who they are, or who they want to be, under the gaze of peers, strangers, and algorithms.

Through algorithmic feedback loops, social media platforms reward visibility and popularity. As Noble (2018) argues, these algorithms are not neutral, they often amplify stereotypes, reinforce inequalities, and prioritise content that drives engagement over wellbeing. Likes, shares, comments, and follower counts act as signals of social value. My own son (aged 10) and daughter (aged 12), although currently only connected on primary school-based platforms, have told me that they choose to only post or share what they think their peers will approve of or find interesting. Even at this young age, they are consciously adapting their online behaviour to fit what they believe their peer expectation is. The result is that young users often tailor their content to gain approval, shifting their behaviour to fit what the platform algorithm rewards, often appearance based or emotionally heightened content. Perloff (2014) notes that such environments can intensify concerns about physical attractiveness and foster self-objectification, particularly among adolescents. So while it can foster creativity, self-expression, and connection, it also fuels a need for external validation.

Papacharissi (2011) describes these phenomena as the “networked self”, where identity is constructed in relation to digital tools, networks, and audiences. In this context, teens may develop a sense of self that is highly performative, focussed not only on who they are, but on how they are seen. This is particularly concerning when trends prioritize physical appearance or controversial content, reinforcing narrow beauty ideals and risky attention-seeking behaviours (Perloff, 2014).

We see empowerment and risk existing side by side. Some young people use social media to build community, advocate for causes, or share talents, reflecting what Jenkins et al. (2016) describes as “participatory culture”, where users don’t just consume content but actively shape and share it. However others may struggle with anxiety, self-doubt, or body image issues linked to constantly comparing themselves, as documented by Perloff (2014) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (2021). Evidence suggests that the pressure to maintain a “likeable” identity online can distort self-perception as young users often shape their content based on peer feedback and platform incentives (Papacharissi, 2011; Boyd, 2014).

Ultimately, identity development in digital spaces is complex and shaped by a mix of peer influence, platform design, and cultural trends (James et al., 2019). While social media can offer powerful tools for self-expression, it can also entrench harmful norms and make self-worth feel dependant on engagement metrics.

Platform Failures and Regulatory Gaps

Despite platform age restrictions, underage users continue to access social media in large numbers (Rideout, Peebles, Mann, & Robb, 2021). Most platforms rely on self-reported ages at sign-up, a method that is easily bypassed by children (Livingston, Stoilova, & Nadagiri, 2019). This lack of robust age verification enables children under 13 to access platforms not designed for their developmental needs or safety.

Algorithm-driven content delivery systems on platforms like TikTok and Instagram are optimised for engagement and often promote emotionally charged or visually striking content (Noble, 2018). While this maximises user attention, it also increases the risk of exposing young users to harmful material, including idealised body standards, sexualised content, and extremist views (American Psychological Association, 2023; James at al., 2019). Meta’s own internal research, leaked in 2021, revealed that Instagram was particularly harmful to teenage girls, contributing to body image issues and mental health struggles (Wall Street Journal, 2021).

YouTube has also come under scrutiny for pushing inappropriate videos through its recommendation algorithm on YouTube Kids, undermining its promise of a child-safe space (Tech Transparency Project, 2022). These platform-level failures suggest that content moderation and algorithmic design are not adequately addressing the needs of young users.

In Australia, the eSafety Commissioner’s reports have consistently highlighted gaps in industry accountability and emphasised the need for stronger protections for children online (eSafety Commissioner, 2025a; eSafety Commissioner, 2025b). Despite growing public concern, industry self-regulation remains the dominant model, with major tech companies continuing to resist oversight that could interfere with profitability (Kidron, 2023). As long as platform design prioritises engagement over wellbeing, and regulatory mechanisms remain weak or unenforced, underage users will continue to face disproportionate risk in digital environments.

Ethical Concerns and Data Exploitation

While today’s youth is spending more time inhabiting online spaces, their growing presence in digital spaces raises urgent ethical questions about privacy, consent, and data exploitation. Unlike adults, minors may not fully understand the implications of data collection, yet there behaviours and actions are being constantly tracked, stored, and profiled by algorithms. As James et al. (2019) point out, children often engage with digital platforms without a full awareness of how their information is being used, creating a concerning gap between participation and informed consent.

Social media platforms profit from collecting user data to personalise content and push targeted advertising. This commercial model, often referred to as surveillance capitalism, treats children’s digital interactions as monetisable assets. Brusseau (2020) argues that these systems reduce digital identity to a bunch of data points, monetising even personal expression. For younger users this means losing a sense of control over how they present themselves online, with algorithms influencing what content they’re shown and even how others see them.

There is also the psychological impacts tied to it all. Being exposed to specific kinds of targeted content, especially posts that push appearance -related pressure or harmful behaviours, can make things worse for teens already struggling. The American Psychological Association (2023) has warned that these algorithm-driven platforms can boost harmful messaging and increase vulnerability, especially in adolescents who are already at risk.

And then we have the issue of consent. Most adults don’t even read or understand the long terms of service agreements let alone our youth, yet their personal data still gets collated on a huge scale, often with little regulation. This raises concerns over the ethical obligations of tech companies that are handling youth data. As Livingstone and Third (2017) stress, children’s rights to privacy and protection online must be prioritised over platform profitability,

In the end, the way young users data is used points to a bigger problem, that there is a clear imbalance of what benefits corporations and what is best for children. Until stronger data protection laws and ethical tech design become the norm, underage users will keep facing risks in an online world designed more for profit than their wellbeing.

The Role of Advocacy and Policy

Lately, there’s been a growing push to tighten up age restrictions and improve verification for underage users on social media. In Australia, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese addressed the issue during an appearance on Sunrise, saying the government is looking into raising the minimum age for social media access to 16(Schrader, 2024). He also touched on the topic again more recently in a casual interview with YouTube creator Ozzy Man Reviews, once again stressing the need to better protect young people online. These comments show that both the public and politicians are starting to take the issue more seriously. Still, many critics argue that actual policy change is lagging behind. As the Guardian has pointed out while age limits are being talked about around the world, there is still a lot of uncertainty about how they would even be enforced. Even with PM Albanese backing a campaign to ban under-16’s from social media, the real world impact remains unclear (Middleton & Taylor, 2024). MP Zoe Daniel put it bluntly, speaking around when it comes to online child safety that governments keep letting tech companies police themselves and it’s our children who are paying the price (Daniel, 2024).

Watch the Ozzy Man Reviews interview here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lmmqy-YI2RU

Advocacy groups and researchers have been and are still pushing for stronger safeguards and greater accountability. UNICEF (2021), for example recommends using age-appropriate design, stricter data protection policies, and frameworks that centre around children’s rights to create safer digital environments. In Australia, the eSafety Commissioner promotes a model called the “Safety by Design”, which urges tech companies to build safety and privacy into platforms from the very beginning (eSafety Commissioner, 2023). But so far, the rollout of these ideas has been slow, and actual enforcement is still pretty limited.

Some researchers, like Ellis and Goggin (2017), argue that education and activism are key to making a difference. Programs that teach digital literacy, things like how algorithms work, what data is collected, and how to navigate online spaces critically and safely, are gaining traction in schools. That being said, these initiatives are not consistently funded or widely adopted yet. Without big-picture reforms and real cooperation across sectors, even the best advocacy work can only go so far.

In the end if we want real change then policy needs to come with enforceable rules and be shaped with kids perspectives in mind. That means lifting up youth voices, holding platforms accountable, and getting governments, educators and tech companies to actually work together. It is the only way we will be able to build a digital world that puts young peoples safety first.

Conclusion

As someone who sees this happening with my own kids, it’s clear that social media plays a huge part in how young people figure out who they are and connect with others and just get involved in the world around them. But for the young people 18 and under, these online spaces still have some major underlying flaws. Most platforms are built to maximise engagement and boost profits, which means they often ignore what younger users actually need in terms of safety and healthy development. As this paper has discussed, the risks go beyond just technical or legal concerns, they are also deeply personal and emotional. Underage users face everything from identity struggles and algorithm-driven pressure to data misuse and a general lack of proper safeguards. These platforms were not designed with them in mind and it shows.

People have definitely been talking more about this lately, including both advocates and politicians, about the need for change, which is a great start. But real reform is still moving slowly. Unless governments start enforcing stronger rules, tech companies commit to designing ethically, and young people actually get a say in shaping the digital spaces they use every day, the gap between the potential of social media and the protection of young users need isn’t going away anytime soon. Hoping tech companies will just do the right thing isn’t enough anymore. If we want the next generation to be safe online, then its time online spaces are built with real care and their well-being at the core. After all, it might not seem urgent until it hits close to home and one day, heavens forbid, it may be your loved one that is at risk.

References:

Vogels, E. A (2022, August 10). Teens, social media and technology 2022. Pew Research Centre. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Rideout, V., Peebles, A., Mann, S., & Robb, M. B. (2021). The Common Sense Census: Media use by tweens and teens, 2021. Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-2021

Pew Research Centre. (2022). Teens, social media and technology 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/11/16/connection-creativity-and-drama-teen-life-on-social-media-in-2022/

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2021). The impacts of social media on children, adolescents, and families. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/127/4/800/65133/The-Impact-of-Social-Media-on-Children-Adolescents

Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research (2014). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6

James, C., Davis, K., Charmaraman, L., Konrath, S., Slovak, P., & Weinstein, E. (2019). Digital life and youth well-being, social connectedness, empathy and narcissism. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/140/Supplement_2/S71/34171/Digital-Life-and-Youth-Well-being-Social

Kidron, B. (2023) Beeban Kidron on why children need a safer internet, Centre for International Governance Innovation. https://www.cigionline.org/big-tech/beeban-kidron-why-children-need-safer-internet/

American Psychological Association. (2023). Health advisory on social media use in adolescence. https://www.apa.org/topics/social-media-internet/health-advisory-adolescent-social-media-use

Maiden, S. (2024) ‘Enough is Enough’: Fed up PM confirms nationwide social media ban. News.com.au. https://www.news.com.au/technology/online/social/enough-is-enough-fed-up-pm-confirms-nationwide-social-media-ban/news-story/63f4be8620e0d7de2347ca33e0ae7e13

Daniel, Z. (2024 September) Time to rein in the technology giants. https://zoedaniel.com.au/2024/09/09/time-to-rein-in-the-technology-giants-the-australian-9-sept-2024/

Middleton, K., & Taylor, J. (2024). Albanese backs minimum age of 16 for social media. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/article/2024/may/21/anthony-albanese-social-media-ban-children-under-16-minimum-age-raised

Papacharissi, Z. (2011). A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites. Routledge.

Boyd, D. (2014). It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. Yale University Press.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

Livingstone, S., Stoilova, M., & Nandagiri, R. (2019). Childrens data and privacy online: Growing up in a digital age. London School of Economics and Political Science. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101283/?_gl=1*1wgnqo6*_ga*MTY4MTA5NjkxOS4xNzQ0MjAwMDUx*_ga_LWTEVFESYX*MTc0NDIwMDA1MC4xLjEuMTc0NDIwMDA3My4wLjAuMA..

Wall Street Journal. (2021). Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic For Teen Girls, Company Documents Show. https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-knows-instagram-is-toxic-for-teen-girls-company-documents-show-11631620739

Tech Transparency Project. (2022). Guns, drugs, and skin bleaching: YouTube Kids still poses risks to children. https://www.techtransparencyproject.org/articles/guns-drugs-and-skin-bleaching-youtube-kids-still-poses-risks-children

eSafety Commissioner. (2025a). Behind the screen: Transparency report – Feb 2025. Office of the eSafety Commissioner. https://www.esafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-02/Behind-the-screen-transparency-report-Feb2025.pdf

eSafety Commissioner. (2025b). Mind the gap: Parental awareness of children’s exposure to online harm. Office of the eSafety Commissioner. https://www.esafety.gov.au/research/mind-the-gap

eSafety Commissioner. (2023). Safety by design: Industry reports and research. Australian Government. https://www.esafety.gov.au/industry/safety-by-design

Brusseau, J. (2020). Ethics of identity in the time of big data. https://philarchive.org/archive/BRUEOI-2

Livingstone, S., & Third, A. (2017) Children and young people’s rights in the digital age. New Media & Society. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1461444816686318

Ellis, K., & Goggin, G. (2017). Disability and social media: Global Perspectives. Routledge.

UNICEF. (2021). Policy guidance on AI for Children. https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/reports/policy-guidance-ai-children

YouTube. (2025). Anthony Albanese talks to Ozzy Man Reviews [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lmmqy-YI2RU

Jenkins, H., Ito, M., & Boyd, D. (2016). Participatory culture in a networked era: A conversation on youth, learning, commerce, and politics. Polity Press.

Hi Shannon Kate, You’re right to ask; it is incredibly difficult to police these issues today. Predatory behaviour isn’t exclusive…