by Ayuni

Abstract

This paper argues that the #KitaJagaKita movement in Malaysia developed an effective model of digital crisis response, facilitating a connection between local grassroots initiatives and institutional support through social media, particularly X (formerly known as Twitter) whereby communities are able to organize support during emergencies. This paper examines the rise and growth of the #KitaJagaKita movement in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the society in Malaysia. The paper explains the impact this grassroots movement had on the efforts to aid the community showing how powerful platforms can be to act when a crisis arises. Through a discussion of the history, trajectory, and social impact of the movement, the study demonstrates how Malaysians use social media to make change during moments of crisis.

Introduction

The paper first examines the emergence and evolution of #KitaJagaKita into March 2020 as a simple effort linking people with essential daily needs. It then follows the growth of the movement into a site and partnerships with NGOs. The paper suggests that the initiative responded with more flexibility to different classes of MCOs (Malaysia’s Movement Control Orders) but most of the changes were to meet the economic challenges experienced in 2021.

Evidence of the sociocultural impact of #KitaJagaKita is presented in the research through social media data analysis and case studies. Not only the movement offered humanitarian support but it also unified the nation in isolation against the virus. It pioneered new paradigms of community organizing, showing how using digital communication and organizing can be deployed to provide support for marginalized groups that are neglected by both formal and informal systems.

Background Overview: The Emergence of #KitaJagaKita

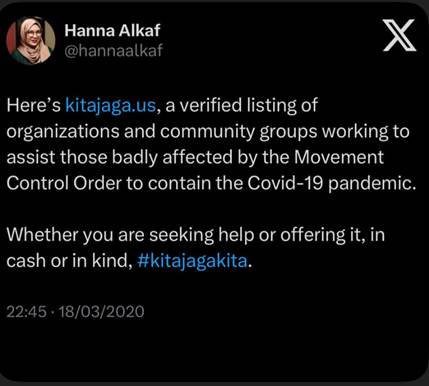

According to Lee (2023), the hashtag #KitaJagaKita, which translates into “we take care of each other” in Malay, trends on social media starting from 18 March 2020 as a simple gesture to appreciate these workers for their dedication and sacrifice during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. But it soon became about much more than a method of public admiration. The transformation of #KitaJagaKita into a national advocacy initiative was first made on Twitter by Malaysian author Hanna Alkaf. Her post generated interest and action and eventually resulted in a grassroots effort, backed by activists and concerned citizens. This birthed the site kitajagakita. com, which is a place where all the various aid and volunteer opportunities popped up in one place across the country.

Figure 1: The original tweet by @hannaalkaf that launched #KitaJagaKita, listing local aid initiatives

Lee (2023) states that when the Movement Control Order (MCO) was implemented to curb COVID19’s spread, many in the public, along with civil groups, began to act. They leveraged the #KitaJagaKita hashtag to promote adherence to the MCO, social distancing and filling urgent needs for medical supplies including masks and protective equipment. Additionally, social media users monitored the implementation of such measures to those who placed them in, aiding in the government’s mission to contain the virus.

Government agencies, particularly the Ministry of Health, also made use of the #KitaJagaKita hashtag in their messaging to promote responsible behaviour among members of the public. By postulating a need for the carrying of shared emotions, the hashtag became a sign of solidarity and cooperation between the public and the authorities in response to a national crisis (Lee, 2023).

The popularity of #KitaJagaKita was significant as it emerged in the aftermath of a political impasse in Malaysia. Before the first MCO was declared, on 1 March 2020, a new political coalition, Perikatan Nasional (PN), took control of the federal government. This shift happened after the previous government, Pakatan Harapan (PH), collapsed in 21 months. Political tensions were already elevated, with rumours of potential party changes and leadership shifts spreading on social media. It was a coalition formed by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) and led by Muhyiddin Yassin (Lee, 2023).

Lee (2023) observed the pandemic has added to a sense of instability and confusion and only a few Malaysians had time to make sense of political developments when Covid-19 struck. Consequently, the #KitaJagaKita movement also mirrored public concern over leadership and governance. Though primarily a humanitarian response, it also became a subtle form of social and political critique. The citizens were not just always helping one another but indirectly screaming at the new government to do the same during a time of national crisis.

#KitaJagaKita used X as the strategic communication backbone of its pandemic crisis response in Malaysia. Dalili and Dastani’s (2020) findings show that the platform, X made it possible for officials to spread critical information quickly while also acting as an emergency warning system when official channels were running behind. More importantly, it enabled critical two-way dialogue citizens in need could tweet requests with, for instance, #KitaJagaKita or #BenderaPutih (White Flag), and volunteers would reply with verified options for assistance. Such rapid information-sharing turned Twitter into a live crisis management interface where community needs could communicate with official relief programs.

The visibility of the hashtag made individuals accountable for their actions, connecting grassroots networks with institutional responders. In Malaysia, social media has been one of the key platforms that social movements have turned towards for tools of communication, organization, and collective action. X, especially, has been especially essential for communities mobilizing during times of crisis. The #KitaJagaKita movement is used as an example of digital platforms that contribute to grassroots activism.

X as a Catalyst for Crisis Response

#KitaJagaKita was born out of the national response during the COVID-19 pandemic phase. It was not just a way of disseminating information, but the hashtag also played an important role as a collective organization tool for mutual aid that immediately linked people in need with those who could provide assistance, either in the form of supplies or cash. X with its ability to share information in real time, provided this and people were able to ask for help, disseminate resources and efficiently organize the relief. According to Leong and Rosli (2021), it solved the problem of addressing difficult-to-track posts on social media by creating a hashtag system to monitor and respond to urgent cases.

From more than just logistics, #KitaJagaKita is a form of solidarity by providing a forum for public discourse. It also helped marginalised voices to be heard and to force authorities to take action against systemic failures. This activism model was distinct from physical activism as it thrived online but also remained focused on direct impact within the community.

On the other hand, turning to social media did come with obstacles, including misinformation and unequal digital access. Still, #KitaJagaKita showed both how social movement processes can be dynamically reshaped through digital means, not to replace offline action, but to complement and to deliver social change. This example demonstrates that in Malaysia, social media is not only a form of communication media, but social media is an integral part of community engagement.

Figure 2: A tweet showing #KitaJagaKita’s community aid in action, documenting successful food delivery to a citizen in need of help

Leong and Rosli’s (2021) findings demonstrate that the movement began when Hanna Alkaf saw so many relief initiatives carried out by different parties on Twitter and gathered them in one place using the hashtag #KitaJagaKita. Within 24 hours, what began for volunteers as an online initiative was turned into a concerted aid system known as kitajagakita.co, then turning it into a cross-platform mobile app. It was in June 2021, during the third MCO when economic pressure was at its peak, that the movement became widespread, and X became the main platform for food banks and mutual aid distribution all over the country. This uprising digital-first movement hit the society like a wave and created an alternative support network to the government. It made crisis response accessible by allowing people who needed assistance to connect directly with people who offered it and uniting a country amid isolation due to lockdown.

By using this platform, both the emerging needs are identified, and resources can be mobilized quickly through real-time communication. More than just a form of material assistance, #KitaJagaKita provides psychological comfort through the presence of community care in uncertain times. The real success of this operation was not only how effective social media was as an awareness tool but became a practical application of how social media could be used to help coordinate large-scale efforts for relief.

The legacy of #KitaJagaKita movement is in establishing a blueprint for community-led crisis responses in the future, and showing that decentralized, digital-first aid networks are possible in Malaysia.

Post-Pandemic Legacy

As Malaysia progressed into the later stages of its Movement Control Order (MCO), the #KitaJagaKita initiative also grew in prominence, particularly with many struggling with their livelihoods in June 2021. The movement expanded its reach throughout the pandemic with the help of key partners such as Mercy Malaysia, and new collaborators like RumahKita and Homes4Heroes. By needing to tackle different challenges throughout the crisis, those collaborations were instrumental in getting things like medical equipment to healthcare workers and places for doctors and nurses who moved for work to stay (Toh, 2020).

The beauty of #KitaJagaKita was that it brought out the khidmat (the act of serving others) spirit from the bottom, the point of the DNA chain. Hanna Alkaf adds that the movement’s success was because many Malaysians from various walk of life came together and with collective effort, they achieved a goal of helping each other. It demonstrated social media and websites used to provide community aid in hard times can be a great combination. In order to ensure that all the assistance efforts were genuine, the #KitaJagaKita team screened each organization that they collaborated with. Their relationship with the group, if they were registered well, had experience in assisting communities and if they managed funds transparently or not.

Toh (2020) reported Covid-19 then continued to impact Malaysia, #KitaJagaKita focused on neglected groups such as refugees, urban poor communities and indigenous people (orang asli). Its philosophy was rooted in the belief that society only advances when everyone advances whereby, we all should be looking out for one another. Though primarily created to offer emergency assistance amid the pandemic, #KitaJagaKita also accomplished another crucial aim in which the campaign helped bridge the geographical divides imposed by lockdowns, reminding Malaysians that they are not alone but rather part of a community.

The movement put in place a framework for others to replicate during future crises. This proved that when citizens use technology to organize themselves to supplement government work on solving big problems, it works. The movement showed that working together and taking responsibility for each other is a way to correct injustices in society. This model for how communities can respond to disasters, and how digital tools can make this easier, is one of the successes of this story.

More crucially, #KitaJagaKita shifted the way Malaysians think about helping each other. Instead, it was not merely providing food, or money, it was in establishing a category of connection within a society, in another word, a community. The movement is a reminder that even in difficult times, compassion, and solidarity can blossom into resilient networks of support.

This paper discusses the way the #KitaJagaKita movement leveraged social media to better bolster community-based support amidst the COVID-19 in Malaysia. This study argued the movement establish an effective model for digital crisis response among Malaysians by linking ground level activity with institutional activity via X (formerly known as Twitter) and showing how social media can facilitate a different kind of collective action during a crisis.

Conclusion

This paper discussed the way the #KitaJagaKita movement leveraged social media to better bolster community-based support amidst the COVID-19 in Malaysia. This study argued the movement establish an effective model for digital crisis response by linking ground level activity with institutional activity via X (formerly known as Twitter) and showing how social media could facilitate a different kind of collective action during a crisis.

The analysis comprises of three main areas. It started with the roots of the movement, illustrating how average citizens began #KitaJagaKita to fill loopholes in assistance during the pandemic. Then it pointed out how the growth of the movement was amplified through X using the platform to marshal resources to meet needs as and when they emerge, particularly in the lockdowns. In the end, the focus was on the social impact, showing how the digital tools enabled the solidarity and provided concrete and effective help to marginalized communities.

In conclusion, this study shows that #KitaJagaKita succeeded in being an effective model of digital crisis response, facilitating a connection between local grassroots initiatives and institutional support through social media, particularly X (formerly known as Twitter) and further investigated both social networking sites and issues that reach across and between different networks.

References

Alkaf, H. [@hannaalkaf]. (2020, March 18). Here’s kitajaga.us, a verified listing of organizations and community groups working to assist those badly affected by the Movement Control Order to contain the Covid-19 pandemic. Whether you are seeking help or offering it, in cash or in kind, #kitajagakita [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/hannaalkaf/status/1240288132626448384?s=46

Dalili, Mahsa & Dastani, Meisam. (2020). The Role of Twitter During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Systematic Literature Review. Acta Informatica Pragensia. 9. 10.18267/j.aip.138.

Lee, C. (2023). #KitaJagaKita: (De)legitimising the Government During the 2020 Movement Control Order. In: Rajandran, K., Lee, C. (eds) Discursive Approaches to Politics in Malaysia. Asia in Transition, vol 18. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5334-7_12

Leong, Pauline & Rosli, Amirul. (2021). Hashtag Campaigns during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Malaysia: Escalating from Online to Offline. 10.1355/9789815011234-003.

Toh, T. (2020, April 3). How a Malaysian author and a group of volunteers created the #kitajagakita initiative. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/lifestyle/culture/2020/04/03/how-a-malaysian-author-and-a-group-of-volunteers-created-the-kitajagakita-initiative

xatyrosdi [@xatyrosdi]. (2021, July 10). Thank you kitajaga.co for the initiative, my friends managed to track one M40 that needed help in Pantai Dalam. Thank you YB @fahmi_fadzil for the food basket too. #KitaJagakita #BenderaPutih [Tweet]. X. https://x.com/xatyrosdi/status/1413729379050348545?s=46

Hi Shannon Kate, You’re right to ask; it is incredibly difficult to police these issues today. Predatory behaviour isn’t exclusive…