Abstract

The following paper explores how the global adoption of social media as a source of political news and discussion has impacted the polarisation and separation of people with opposing political ideologies and will investigate the mechanism through which this is actioned. This paper argues that social media does contribute to the intensity of political opinion and inhibits the liklihood a platforms userbase will seek out and explore information with opposing ideals. It will also define and investigate the major contributing factors being echo-chambers, filter bubbles, misinformation and disninformation. This ultimately contributes to tribalist mentalities further enforcing division in the general populace of a given nation. While this paper has a particular focus on U.S. politic specifically, the arguments made and evidence provided are relevant to the politics of any democratic nation.

“The global adoption of social media as a source of political news and discussion contributes to the polarisation and separation of people with opposing political ideologies“

The rapid and global rise of social media has quickly changed the way we connect, communicate and interact in the modern age. From how we receive and share news to staying in touch with friends and family the impacts cannot be overstated. This is no less true for politics in which the last twenty years have seen a dramatic increase in the divide between people of opposing political ideologies, particularly in the United States (Karlsson, 2024). This essay will investigate the link between the growth of social media and its influence on the division of people with opposing political ideologies. It will achieve this by first gauging the breadth of the US population that engage in political discourse or receive politically related news and events through social media. It will then investigate if, and to what degree, social media platforms contribute to political polarisation of its users through the following three mechanisms most related to online discourse and ideological polarisation: filter bubbles, echo chambers and misinformation.

While this essay is relevant to politics and social media in any democratic nation and does reference events from a variety of countries, the unique global implications and recent volatility of US politics has resulted in an abundance of resources examining politics in the United States specifically. As such, this essay focuses on the impacts to the US population. This will further serve to limit differing cultural impacts on collected data.

The Social Media Userbase

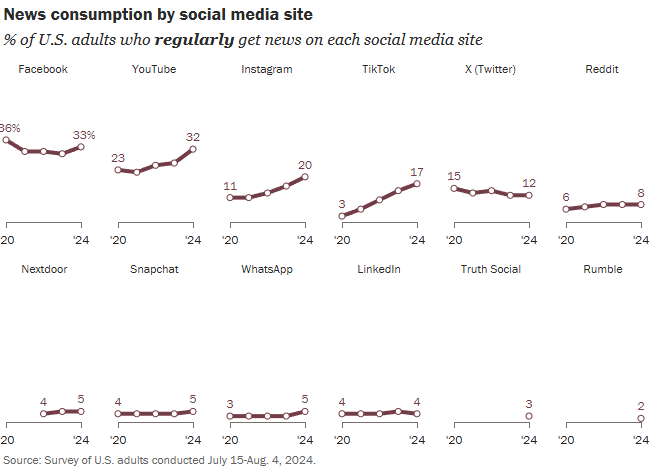

The results of a Survey conducted by Pew Research in 2024 found that, of more than 10,000 people surveyed, more than half of adults in the U.S (54%) get at least some of their political news from social media with that number increasing year on year across most social media platforms. Two thirds of those surveyed were said to get their political news from Facebook or YouTube with the remainder dispersed across other major social media platforms. (Liedke & Wang, 2024)

Of those surveyed that said they regularly use social media as a news source, their age, gender and political alignment, as well as a number of other factors, differed greatly. (Liedke & Wang, 2024) Additionally, engagement by younger demographics has considerably increased with the use of social media. Previously, older demographics were a larger contributor to political discourse as they were more likely to read newspapers and watch broadcast news such as radio and television (Ara, 2022)

These findings demonstrate that social media as a source of political news and discourse has the potential to be a considerable influence on public opinion for the general population and not only for a specific age group or demographic. It also establishes the breadth of impact that social media bi-products such as echo chambers, filter bubbles and misinformation may have.

Echo Chambers

Echo chambers and filter bubbles are loosely defined concepts with often subtle differences in meaning. For the purpose of this essay, echo-chambers are defined as clusters of users with a unified opinion, ideology or interest that primarily discuss and share content that support their existing common ideals within their own community. This results in limited exposure to media, content and discussion with opposing ideals. (Franziska et al 2016 p3-4). Our psychological tendency to subconsciously favor information that aligns with our own pre-existing views as opposed to contradicting information heavily contributes to the development of echo chambers (Garimella et al., 2018)

The inherent limiting of exposure to opposing ideals caused by both echo-chambers and filter bubbles considerably hinders its members ability to challenge their own beliefs or consider the beliefs and arguments of opposing views. Even in the event the ideals of the echo-chamber are considered “positive” the lack of exposure to opposing ideals restricts its members ability to empathise with potentially legitimate concerns of others. (Ranalli 2023)

Echo chambers are of particular concern in democratic countries as people become more polarised in their political opinions and are less inclined to explore views outside of their echo chamber. Both Facebook representatives and former US presidents have voiced concerns that echo-chambers “might hamper the deliberative process in democracy” (Garimella et al., 2018)

“The emergence of echo chambers on social media has significant implications. Re-enforcing social networks have been shown to reduce informational cross-pressures and thereby decrease attitudinal ambivalence” (Rudolph 2011)

A 2021 research article published by the University of Oslo supported the existence of echo-chambers in social media noting that they were particularly dominant in Facebook and X (formerly Twitter). They concluded that they form through homophily of interpersonal networks and the users bias towards like-minded peers. (Cinelli et al 2021). Additionally, findings suggest that social media applications structured around social networks and algorithm driven news feed fostered the development of echo-chambers. (Cinelli et al 2020, p.6), (Kitchens et al., 2020) while inversely, social media platforms with a user customisable news feed such as Reddit were considerably less prone to the formation of echo-chambers (Cinelli et al., 2021) This demonstrates that despite the echo-chambers being a largely user driven issue, algorithmic news feed driven by social networking features are still largely contributing factors.

Filter Bubbles

Similarly, filter-bubbles result in the limiting of a user’s exposure to content with opposing ideas and opinions. Where echo chambers are user driven however, filter bubbles refer to the potential consequences of personalized feeds in which users are isolated from differing perspectives through a consistent feed of content that supports a users existing beliefs (Franziska et al 2016 p3), (Areeb et al., 2023) The impact is the reinforcement of existing beliefs without the means to challenge them or consider alternative avenues of thought further polarising users. (Areeb et al., 2023) Furthermore, unlike echo-chambers, filter bubbles are largely invisible to the user as they are generally unaware of the inputs driving their personalised responses and only receive what the algorithm delivers. (Burbach et al., 2019) This is of particular concern as there is evidence to suggest that if a user is aware they’re in a filter bubble the consequence can be eliminated however most users are unaware an algorithm filters their content, let alone that they’re inside a filter bubble (Burbach et al., 2019) News feeds based on social networking platforms are especially prone to encouraging both echo-chambers and filter-bubbles as they are considerably more likely to feed content supporting the existing beliefs not just of a given users but the beliefs of those in their the immediate social network as well. (Kitchens et al., 2020)

Furthermore, a 2018 research paper on political discourse in social media concluded that echo chambers around politically contentious topics exist within Twitter and that bipartisan users (those with more centrist ideologies) have fewer retweets, favourites and endorsements than politically extreme content (Garimella et al., 2018) which suggest that X algorithmically promotes polarised or extreme content over bipartisan content. This highlights concerns that in addition to encouraging the development of echo-chambers, mediation between opposing beliefs is potentially being stifled. (Solovev & Pröllochs, 2022)

Filter bubbles have also been shown to affect the formation of a person’s political opinion. The effects are strongest when a user is already in an echo-chamber with mostly ideologically moderate members or members that already share the ideals of the content delivered by the existing filter bubble. Political parties have in the past developed their campaigns to take advantage of social media algorithms to garner supporters. In the 2016 U.S presidential election for example, the republican party analysed social media profiles and tailored their campaign to win those voters. (Burbach et al., 2019)

While filter bubbles are a serious concern and demonstrated to exist on some social media applications, particularly those with social networking features and algorithms such as Facebook and X (formerly Twitter), there are some conflicting studies which suggest that filter bubbles are not as common as first thought. (Bret 2020) Some studies have even indicated that relying on search engines and automated news feeds for content even produced a slightly more diverse exposure to news. (Arguedas 2022)

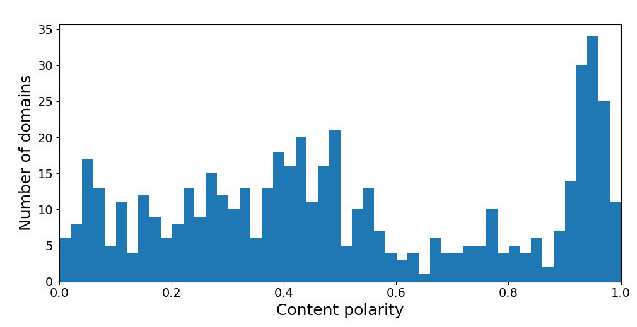

Disinformation or “Fake News”

The final mechanisms this essay explores are misinformation and disinformation or “fake news”. Both misinformation and disinformation are defined as factually incorrect information, where as misinformation is shared when the author is unaware of the information’s in-accuracy and disinformation is shared regardless of whether the sharing party is aware that the information is incorrect (Jerit & Zhao, 2020) Both echo-chambers and filter bubbles are associated with increased exposure to misinformation or “fake news” (Rhodes, 2021) though an analysis of scientific articles indicates that “fake news” has become of considerable more scientific interest than “echo chambers” or “filter bubbles” (Zimmer, 2019)

While misinformation and disinformation is common in all forms of media, the ease of use and speed at which information can be published on social media, makes it particularly prevalent. (Muhammed & Mathew, 2022) Because of the rapidly generated and changing nature of social media content, it can be difficult for social media users to decipher where information originated from and whether it is from a trustworthy source. (Torres et al., 2018) Additionally, it has been demonstrated to resurface multiple times after first publication as opposed to factually correct information which is less likely to do so, further contributing to the efficacy of misinformation. (Shin et al., 2018) Confirmation bias also exacerbates the impacts of fake news related to politics as readers are considerably more likely to engage with, and accept the validity of, information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs and political affiliations and reject information that challenges it (Muhammed & Mathew, 2022) (Zimmer, 2019) As a result, fake news can create or fuel echo chambers and further polarise their members. (Cinelli et al., 2021)

In addition to the complexities of combating fake news, evidence suggests that X (formerly Twitter) encourages polarised opinions and the spread of misinformation. A study of bipartisan users likes, retweets and shares found that posts with more centrist opinions received considerably less engagement (Garimella et al., 2018) this is likely a bi-product of algorithms designed to drive interaction and promote virality ultimately reinforcing existing prejudices and limiting outside exposure to alternative views. (Wafiq, 2023)

While echo chambers and filter bubbles erode democratic processes, misinformation has been directly attributed to impacting the outcome of the 2016 U.S presidential election (Levin 2017) and is considered “a severe threat to public interest”. (Muhammed & Mathew, 2022) As an example, social media misinformation resulted in public health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic including an incident in India where a misinformation campaign related to COVID-19 resulted in physical violence towards a minority religious group (Muhammed & Mathew, 2022) Misinformation is now a commonplace problem that has spread well beyond the internet and social media. (Watson 2024)

In conclusion, misinformation, echo-chambers and filter-bubbles have all impacted political polarisation to varying degrees of severity. While social medias contributions to modern discussion of ideals have not been entirely negative, in some instances, even slightly increasing user exposure to opposing ideals being evident, the evidence of existing echo-chambers and filter bubbles and most damagingly, the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation through social media platforms indicates that social media has likely had a considerable impact on the polarisation of its user bases. While the severity varies from platform to platform, the evidence suggests that by their very design, social media platforms as a whole are contributing to political division and will continue to do so.

References

Ara, Y. (2022). The Impact Of Social Media On Political Discourse: A Multidisciplinary Analysis. Migration Letters, 19(S2), 1518–1528. https://migrationletters.com/index.php/ml/article/view/10374

Areeb, Q. M., Nadeem, M., Sohail, S. S., Imam, R., Doctor, F., Himeur, Y., Hussain, A., & Amira, A. (2023). Filter bubbles in recommender systems: Fact or fallacy—A systematic review. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 13(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1512

Arguedas, A., Robertson, C., Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. (2022, January 19). Echo chambers, filter bubbles, and polarisation: A literature review. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/echo-chambers-filter-bubbles-and-polarisation-literature-review

Brest, A. (2020, July 30). Filter bubbles and echo chambers. Fondation Descartes. https://www.fondationdescartes.org/en/2020/07/filter-bubbles-and-echo-chambers/

Burbach, L., Halbach, P., Ziefle, M., & Calero Valdez, A. (2019). Bubble Trouble: Strategies Against Filter Bubbles in Online Social Networks. Digital Human Modeling and Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics and Risk Management. Healthcare Applications, 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22219-2_33

Cinelli, M., Morales, G. D. F., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Starnini, M. (2021). The Echo Chamber Effect on Social Media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9), 1–8. PNAS. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

Cinelli, M., Morales, G. D. F., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Starnini, M. (2020). Echo Chambers on Social Media: A comparative analysis. Arxiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.09603

Figà Talamanca, G., & Arfini, S. (2022). Through the Newsfeed Glass: Rethinking Filter Bubbles and Echo Chambers. Philosophy & Technology, 35(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00494-z

Garimella, K., De Francisci Morales, G., Gionis, A., & Mathioudakis, M. (2018). Political Discourse on Social Media: Echo Chambers, Gatekeepers, and the Price of Bipartisanship. Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference on World Wide Web – WWW ’18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3178876.3186139

Hampton, K. N., Shin, I., & Lu, W. (2016). Social media and political discussion: when online presence silences offline conversation. Information, Communication & Society, 20(7), 1090–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2016.1218526

Jerit, J., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Political Misinformation. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-032814

Karlsson, C.-J. (2024). Divided we stand: The rise of political animosity. Knowable Magazine. https://doi.org/10.1146/knowable-081924-1

Levin, S. (2017, September 27). Mark Zuckerberg: I regret ridiculing fears over Facebook’s effect on election. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/sep/27/mark-zuckerberg-facebook-2016-election-fake-news

Liedke, J., & St. Aubin, C. (2024, September 17). Social Media and News Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center; Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/

Muhammed , S. T., & Mathew, S. K. (2022). The Disaster of misinformation: a Review of Research in Social Media. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, 13(4), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-022-00311-6

Ranalli, C., & Malcom, F. (2023). What’s so bad about echo chambers? Inquiry, 37–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174x.2023.2174590

Rhodes, S. C. (2021). Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News: How Social Media Conditions Individuals to Be Less Critical of Political Misinformation. Political Communication, 39(1), 1–22.

Rudolph, T. J. (2011). The Dynamics of Ambivalence. American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 561–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00505.x

Schleffer, G., & Miller, B. (2021). The Political Effects of Social Media Platforms on Different Regime Types. Texas National Security Review. https://tnsr.org/2021/07/the-political-effects-of-social-media-platforms-on-different-regime-types/

Shin, J., Jian, L., Driscoll, K., & Bar, F. (2018). The diffusion of misinformation on social media: Temporal pattern, message, and source. Computers in Human Behavior, 83, 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.008

Solovev, K., & Pröllochs, N. (2022). Hate Speech in the Political Discourse on Social Media: Disparities Across Parties, Gender, and Ethnicity. Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, 3656–3661. https://doi.org/10.1145/3485447.3512261

Torres, R., Gerhart, N., & Negahban, A. (2018). Combating Fake News: An Investigation of Information Verification Behaviors on Social Networking Sites. In scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/4ae27273-e35c-4f5f-9c7f-3ca703c3448c

Wafiq, N. F. (2023, May 11). The Power of Social Media: Shaping Political Discourse in the Digital Age. Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2023/05/11/the-power-of-social-media-shaping-political-discourse-in-the-digital-age/

Watson, A. (2024, January 9). Topic: Fake news in the U.S. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/3251/fake-news/#topicOverview

Zimmer, F. (2019). Echo chambers and filter bubbles of fake news in social media: Man-made or produced by algorithms? https://huichawaii.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Zimmer-Franziska-2019-AHSE-HUIC.pdf

Hi Shannon Kate, You’re right to ask; it is incredibly difficult to police these issues today. Predatory behaviour isn’t exclusive…