Abstract

With the growth of social networking sites and their ongoing development affordances, understanding how connections are made and what social changes may occur is key to knowing an individual’s stance and affiliation in the online realm. This paper analyses the impact that Pinterest—as an image and video-based social networking site—can have on a formed networked public of young girls and women who enjoy the “pinning” activity and the creation of vision boards. It is argued that although Pinterest has a public perception of being a safe and positive social networking site compared to similar services, it has its downside, which may negatively affect young girls and women as their vast major audience. Specifically, Pinterest’s algorithm can create a filter bubble where diversity may be hindered, an environment where social comparison and aesthetic obsessions are enforced, targeted advertising results in consumeristic and materialistic behaviours, and the rise of privacy concerns. Some fundamental research methods that are utilised to provide evidence and examples in support of the argument in this paper, among others, are through scholarly resources, observation and data analysis obtained across different social media platforms, and following news articles whenever necessary. This paper underscored the importance of critically examining and challenging the power of a social networking site and its ability to create constructive or harmful influence on its users.

Amendment: Please note that this paper was finalised on 8 April 2024, before implementing Pinterest’s updated policies regarding inclusive and diverse search filters, including introducing features such as hairstyle and body type filters. While these updates were officially introduced in 2018 and 2024, respectively, they were not accessible on my device until after completing my research and writing process for this conference paper.

Introduction

When elements such as aesthetics, visuals, inspirations, and mood boards are mentioned, Pinterest is considered the top go-to social media platform, especially for girls and women. From women’s clothing, home decor, food recipes, and beauty trends to wedding inspirations, Pinterest seems to be the “visual discovery (search) engine” where they can find heaps of various Pins and proceed with saving and assigning them to different boards as how they would like to organise it (Pinterest, 2024, para. 1). Some might associate Pinterest as a sole search engine platform—even the Pinterest website itself seems to like to define itself as such—, but it can also be referenced as a social networking site due to its nature of allowing its users to build their desired profile, connect with other users, and create social networks—in this case, through sharing images or videos (Mull & Lee, 2014). As a social networking site, Pinterest is often overlooked and claimed by people as a safe social networking site since, at the surface, it does not have any dramas, not many discussions take place inside the app, just pretty pictures and aesthetic boards to be made (Jacimariesmith, 2023, user59840183, 2024, Datboykb, 2024). While most people often view Pinterest as a social media platform that brings nothing but a positive impact through its aesthetically pleasing personalised content, it can also destructively affect a networked public across platforms, consisting of young girls and women. The negative impact can be generated when the algorithm projects a filter bubble, making it easier to reduce exposure to diversity, embed high or unrealistic standards, source consumerism and materialistic behaviours, and raise privacy concerns.

Figure 1

People’s Common Views / Opinions on Pinterest

Note. Pictures are screenshots compiled from different sources (i.e. TikTok, Twitter, Reddit, and Websites such as Medium, Lanthorn, and UCCS Student Newspaper). All contents screenshotted are the property of their respective owners.

Lack of Diversity & Limited Representation

Through algorithms, a big part of the Pinterest searching activity, users may be trapped in their bubbles of assumed recommended visual representations that must be challenged by adding keywords that disclose diversity or display new variations. It can be acknowledged that Pinterest’s algorithm displays favourable content that appeals to its users’ interest by recognising past searches and their saved Pins if users have heaps of activity variation and time on the platform, which drives its users’ engagement and attention span in the app (Jing et al., 2015). On the other hand, the adverse implication to be critically investigated is that once a visual filter bubble is built, it strays users away from other perspectives or flipside visual representations to be showcased. In addition, Pinterest often show results of “ideal and common” women imagery whenever general keywords are typed into the search bar (Leckie, 2015, p. 8). For instance, when typing “hairstyle” or “haircut ideas” to be searched, most of the photo results that will come out are white and east asian women with straight hair. Keywords like “curly”, “wavy”, “black women”, or “ethnic women” need to be added to break the results and show more diversity (Leckie, 2015, p. 8). That said, Pinterest assumes and enforces a perception of traditional, expected, and stereotypical women. This generic assumption not only occurs inside Pinterest but also impacts the networked public across other platforms, including TikTok. Based on research and observation, a randomiser filter on TikTok called “How Pinterest sees me” was made by user @stefaniacocchiara; once the filter is generated, four categories will be displayed—celebrity, outfit, aesthetic, and quote (Cocchiara, 2024). It has now reached 149.3k videos made using this filter. Though, understandably, the options inserted by the creator for the filter may be limited, it is fascinating to observe that most of the results given across all these users have at least the same picture in one of the categories. Interestingly, when being crosschecked back on the Pinterest platform, if the generic category keywords, such as “celebrity” or “quote”, are searched, the options of pictures picked for the filter in TikTok by the creator are the first generic ones that showed up. These examples imply that, frequently, unless a specific keyword is used to challenge the algorithm, the Pinterest algorithm creates filter bubbles for users, characterising a lack of diverse representations and hindering an open door to different personalised results.

Figure 2

“How Pinterest Sees Me” TikTok Filter by Stefania Cocchiara

Note. Screenshotted from Stefania Cocchiara’s TikTok Filter Page, 2024 (https://vt.tiktok.com/ZSFbxtRKJ/). Copyright Stefania Cocchiara, 2024.

Social Comparison & High Beauty Standards

Along with the stereotyped and generic results showcased come the embedded high and unrealistic beauty standards that may destructively affect the online network of young girls and women and how they perceive and present themselves digitally and in real life. Pinterest’s affordances and distinct image as a social media platform for aesthetic visuals create a further form of networked public, an affective public that highly emphasises conventionally beautiful visuals. Those involved in an affective public are usually connected or disconnected at a certain emotional level or bound through commonalities that they have (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). In a positive light, it can be admitted that as a feminised-centred platform, Pinterest built an affective public where women from different backgrounds commonly share happiness through the activity of pinning ideas and have a shared desire and goal that they can invest outside the digital realm (Wilson & Yochim, 2015). Wilson and Yochim (2015) mentioned a case in which mothers can use Pinterest to collect creative inspiration to be applied in their households. While that might have been the case years ago, Pinterest has now leaned toward forming an affective public where young girls and women create high physical expectations of themselves, leading to social comparisons. A recent example is the emergence of the “Pinterest girl” trend across platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter. When the keyword or hashtag “Pinterest girl” is typed, the shared characteristics incorporate high-quality images, aesthetically pleasing visuals, conventionally attractive people, flawless imagery, and an outstanding sense of fashion style. While this trend can be commonly utilised for inspiration where women may support one another, it is also likely for women to compare themselves to each other instinctively. Arguably, Pinterest’s visual format can trigger subconscious thoughts that lead people to support a certain body type and to drastic weight-loss methods (Lewallen & Behm-Morawitz, 2016). Furthermore, the nature of Pinterest as an image-sharing SNS also affects self-presentation, which comes hand-in-hand with self-monitoring (Kim et al., 2017). Although recent research stated that women on Pinterest have low self-monitoring compared to Instagram—meaning that the social environment does not influence them and is more asserted with their real selves—the difference is still insignificant (Kim et al., 2017). Accordingly, Pinterest’s affordances, content, and algorithms form an affective public of young girls and women where social comparisons and highly conscious self-presentation surface due to the engraved perfectionism in their digital social environment.

Figure 3

Compilation of the “Pinterest Girl” Content Across Platform

Note. Pictures are screenshots compiled from different sources (i.e. TikTok, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram). All contents screenshotted are the property of their respective owners.

Materialistic Behaviours & Consumerism

The notion of young girls and women pursuing an idealistic version of themselves through their Pinterest boards can then continue to develop and influence consumerism, impulsive buying, and materialistic behaviours. On top of its visual and aesthetic, Pinterest is closely associated with its displays of products, resulting in consumption by its users (Almjeld, 2015). Considering that Pinterest’s audience is mostly women, including those with the financial ability to purchase goods, the platform has become a target for advertisers to promote their products (Reuters, 2013, as cited in Almjeld, 2015). From advertisers’ point of view, Pinterest is an opportunity to grow their brand and widen exposure to their products with virality in mind (Phillips et al., 2014). At the same time, this indicates that pinners are constantly bombarded by advertisements that offer expensive branded goods, merchandise, various clothing, home furniture, make-up and skincare products, and many others. These advertisements are especially supported by Pinterest’s video ads feature, the algorithm itself, and the affordance of having an external link attached to the post, directed to the brand website or an e-commerce website as a “direct-marketing channel” (Sloane, 2019, p.3). Through those external links and repeated exposure to similar advertisements, the respective audience becomes part of an imagined collective within the networked public where consumerism and materialistic behaviours may be normalised. Consequently, this will also result in pursuing social validation by possessing materialistic goods. While it can be recognised that these direct advertisements can merely inspire some and be useful for finding resources for women’s visual boards, they can also grow overconsumption practice and engrain societal and cultural pressure. Based on the statistics provided by Pinterest Business (2024), “shoppers on Pinterest spend double more per month than people on other platforms,” and “45% of 25–34-year-old millennial Pinterest users say they have bought something after coming across sponsored material on the platform”. This consumption can further be seen through videos like “Pinterest-inspired haul” or “Pinterest-inspired room makeover”, which are uploaded and shared on other platforms like YouTube and TikTok. Though these sorts of videos may enhance an individual’s creativity and are their own personal rights, when overconsumption happens and it reaches a less appropriate target audience—for example, most teenage girls who are not financially capable of independently purchasing goods—it relates to the point of stimulating a high aesthetic obsession and the idea of curated or high monitored self. Hence, it is crucial to note that even if visual boards and other Pinterest affordances may positively inspire young girls and women, it is also possible that consumeristic and materialistic behaviour, accompanied by the pressure of getting social recognition of oneself, might occur.

Figure 4

Example of Promoted Content with Its External Link Attached on Pinterest

Note. Pictures are screenshots compiled from promotional content showcased on Pinterest. All contents screenshotted are the property of their respective owners.

Figure 5

Example of “Pinterest-Inspired” Content on YouTube

Note. Pictures are screenshots compiled solely from YouTube. All contents screenshotted are the property of their respective owners.

Privacy Concerns

Regardless of how safe Pinterest seems to be perceived by the public compared to other social networking sites, there have been cases when young girls and women had to deal with privacy concerns. Like Facebook and Instagram, Pinterest, as a social network site, tends to have a stronger network effect, meaning that even though privacy concern arises, most users will presumably still use the service, considering that their connections, network, and persona are already built within the service (Engels, 2019). Admittedly, data usage is beneficial in creating personalised results for each user and a significantly better experience (Engels, 2019). However, as digitalisation advances, it has become more effortless for other parties to receive detailed user data profiles (Kasakowskij et al., 2021). Pinterest gathers information from users’ profile registration and forwards it to them, often for targeted advertising (Kasakowskij et al., 2021). This collection also suggests that exploitation and misuse of data might occur simultaneously, even if Pinterest has recently upgraded its privacy policy. Through an investigation, NBC News revealed that Pinterest’s algorithm and recommended search engine have made it easier for pedophiles and grown men to discover minor photos that they can easily sexualise (Cook, 2023). After the investigation was exposed, Pinterest upgraded its safety measures by having parental control features and banning certain keywords (Perez, 2023). Keywords such as “young girls” and “hot kids” that used display results have now been banned, yet some other keywords such as “girl toddler”, “toddler outfits”, and “teenage girl outfits” when typed into the search bar remain displaying results, some showcasing young girls with revealing clothes and inappropriate comments as a response, which in the end, questions and challenges further privacy standards to be taken into consideration. In another case, a Pinterest user shared a video on TikTok of how she found out that her picture that had been publicly shared on Pinterest had been edited and morphed by someone else and re-uploaded to Pinterest (Lauren, 2021). Some comments expressed how they had similar experiences, and others expressed how, due to such matters, they remain having a private online presence. This phenomenon implies that users may become more aware of how they present themselves online, whether to remain authentic or anonymous and how they network and connect with others on or across other platforms. After all, privacy remains an issue due to the misuse of data or exploitation of images, leaving aside Pinterest’s reputation as a safe space.

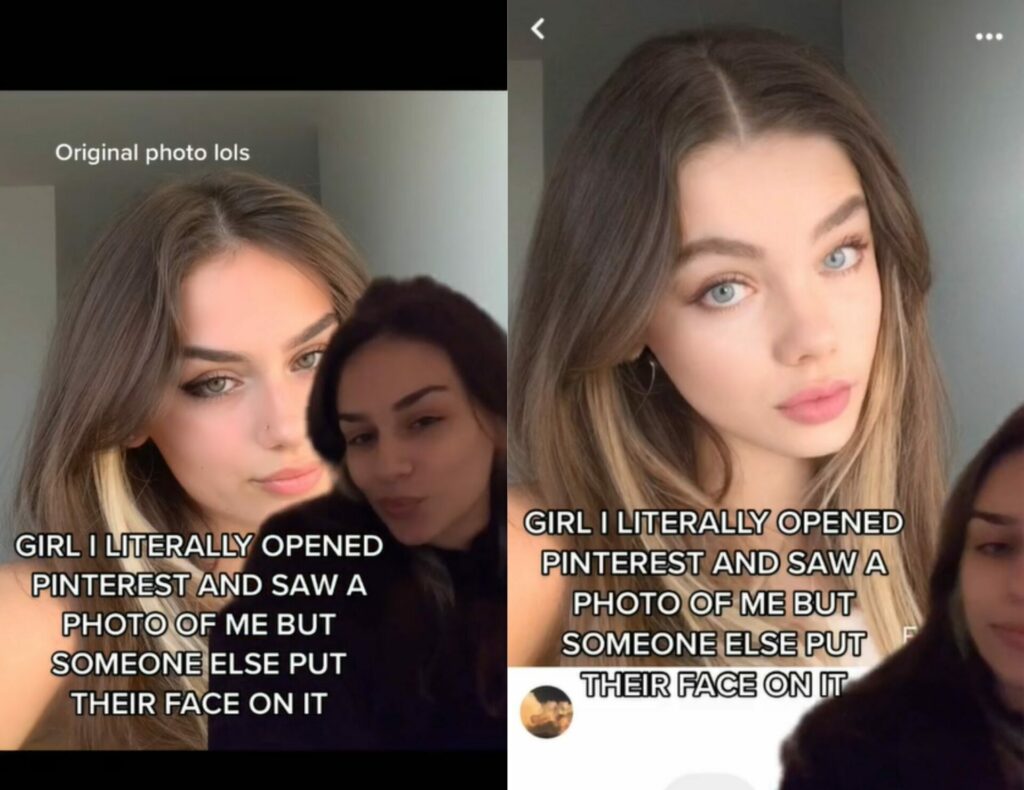

Figure 6

Case: Altered Image of an Individual’s Facial Portrait on Pinterest

Note. Screenshotted from Lauren’s TikTok Page, 2024 (https://www.tiktok.com/@lpgswag/video/7000941196264754437?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7354919848897627666). Copyright Lauren, 2024

CONCLUSION

Despite some social networking sites often having a good public perception of the online network built in or outside the platform, it is important to reapproach how it negatively or positively affects users and how they are being used, considering the affordances and contents. Seemingly, Pinterest offers an example of a social networking site that forms visually oriented women and young girls networked public and positively contributes to their creative process through inspiration boards and goals-represented vision. Nevertheless, it also comes with consequences due to its algorithm, including lack of diversity and representations in results, unrealistically high visual standards and social comparisons, overconsumption and materialistic behaviours caused by advertisements, and the reality of privacy issues. It is acknowledged that limitations are present in this paper as coverage of the audience only includes women and young girls as a major audience of Pinterest, not including how it would differently affect men and young boys. It is also essential to consider that other social networking sites based on image or video sharing, for example, Instagram, compared to Pinterest, might have different formations of networked publics and how it contributes to making changes. On a broader implication, this study allows reassessment and evaluation of self-presentation online and in real life and how connections are made when using social networking sites.

REFERENCE LIST

[user59840183]. (2024, February 17). I love Pinterest. No drama, no talking, just pretty pictures and vibes [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@user59840183/video/7336547317132053765?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7291483277000197640

Almjeld, J. (2015). Collecting girlhood: Pinterest cyber collections archive available female identities. Girlhood Studies, 8(3), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.3167/ghs.2015.080303

Cocchiara, S. [stefaniacocchiara]. (2024, March 7). How Pinterest sees me [Video / Filter]. TikTok. https://vt.tiktok.com/ZSFbxtRKJ/

Cook, J. (2023, March 9). Men on Pinterest are creating sex-themed image boards of little girls. The platform makes it easy. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/internet/pinterest-algorithm-young-girls-videos-grown-men-investigation-rcna72469?cid=sm_npd_nn_tw_ma

Datboykb [king_benjyyyyy]. (2024, February 17). Me explaining that I like Pinterest so much because it’s just media without the social aspect and I get to [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@king_benjyyyyy/video/7200870125254315307?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7291483277000197640

Engels, B. (2019, April). Digital first, privacy second? Digital natives and privacy concerns [Paper Presentation]. 17th International Conference on e-Society 2019, Cologne, Germany. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334553215_DIGITAL_FIRST_PRIVACY_SECOND_DIGITAL_NATIVES_AND_PRIVACY_CONCERNS

Jacimariesmith [jacimariesmith]. (2023, June 4). Me explaining that Pinterest is the best social media app because when you scroll you have no concept of who [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@jacimariesmith/video/7240495741679127854?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7291483277000197640

Jing, Y., Liu, D., Kislyuk, D., Zhai, A., Xu, J., Donahue, J., & Travel, S. (2015, August 10). Visual search at Pinterest [Paper Presentation]. KDD ’15: Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain. https://doi.org/10.1145/2783258.2788621

Kasakowskij, T., Kasakowskij, R., & Fietkiewicz, K. J. (2021). “Can I pin this?” The legal position of Pinterest and its users: An analysis of Pinterest’s data storage policies and users’ trust in the service. First Monday, 26(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v26i7.11477

Kim, D. H., Seely, N. K., & Jung, J. (2017). Do you prefer, Pinterest or Instagram? The role of image-sharing SNSs and self-monitoring in enhancing ad effectiveness. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.022

Lauren [lpgswag]. (2021, August 27). Girl I literally opened Pinterest and saw a photo of me but someone else put their face on it [Video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@lpgswag/video/7000941196264754437?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7354919848897627666

Leckie, M. C. (2015). Undo it yourself: Challenging normalizing discourses of Pinterest? Nailed it! Harlot: A Revealing Look at the Arts of Persuasion, 14(9), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.15760/harlot.2015.14.9

Lewallen, J., & Behm-Morawitz, E. (2016). Pinterest or Thinterest?: Social Comparison and Body Image on Social Media. Social Media + Society, 2(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116640559

Mull, I. R., & Lee, S. (2014). “PIN” pointing the motivational dimensions behind Pinterest. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.011

Papacharissi, Z., & Trevey, M. T. (2018). Affective publics and windows of opportunity: Social media and the potential for social change. In G. Meikle (Ed.), The routledge companion to media and activism (1st ed., pp. 87–96). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315475059-9/affective-publics-windows-opportunity-zizi-papacharissi-meggan-taylor-trevey?context=ubx&refId=06ae96da-d119-48e1-a587-24d656d1787b

Perez, S. (2023, April 12). After an investigation exposes its dangers, Pinterest announces new safety tools and parental controls. Tech Crunch. https://techcrunch.com/2023/04/12/after-an-investigation-exposes-its-dangers-pinterest-announces-new-safety-tools-and-parental-controls/

Phillips, B. J., Miller, J., & McQuarrie, E. F. (2014). Dreaming out loud on Pinterest: New forms of indirect persuasion. International Journal of Advertising, 33(4), 633–655. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-33-4-633-655

Pinterest Business. (2024). Getting started. Pinterest Business. https://business.pinterest.com/en-au/getting-started/

Pinterest Business. (2024). Small business resources for Pinterest. Pinterest Business. https://business.pinterest.com/en-au/small-business-resources-for-pinterest/

Pinterest. (2024). All about Pinterest. Pinterest Help Center. https://help.pinterest.com/en/guide/all-about-pinterest

Sloane, G. (2019). PIN IT TO WIN IT: PINTEREST BETS BIG ON SHOPPING. Advertising Age, 90(18), 20. https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/pin-win/docview/2297251693/se-2

Wilson, J., & Yochim, E. C. (2015). Pinning happiness: Affect, social media, and the work of mothers. In E. Lavine (Ed.), Cupcakes, Pinterest, and ladyporn: Feminized popular culture in the early twenty-first century (1st ed., pp. 232–248). University of Illinois Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=4306038&ppg=243

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.