Abstract

As video games industries move at a rapid pace in terms of what games can offer, there has been an increased emphasis to take seriously the study of communities formed through online gaming. This conference paper aims to provide a pragmatic approach that communities formed within online gaming, can be advantageous, beneficial and genuine, countering against traditional studies that were sceptical to the rise of the digital age. This paper explores 3 very different kinds of gaming communities to reveal the validity of virtual gaming communities within different contexts. Utilising a variety of academic sources, which supports and counter-argues, this paper discovers that games are no longer as casual and simple as they seem, they are growing in complexity and will continue to draw serious discussions on its impact of people’s lives and communities.

KEYWORDS: Online Gaming, Virtual Worlds, Traditional Games, Digital Games, Digitisation, Internet, Third place, MMORPG, Guilds, FIFA, GTA, Facebook, Farmville, Web 2.0, ARG.

Introduction

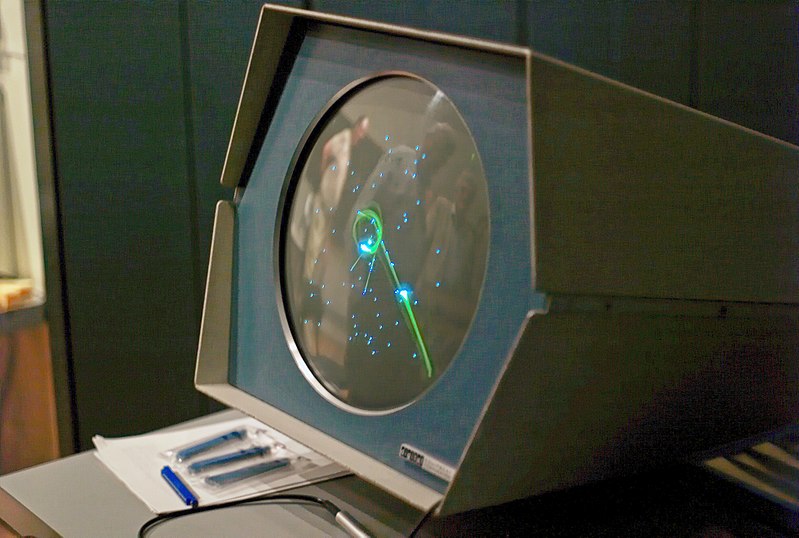

Old-fashioned games night consisting of Uno, Monopoly or Scrabble usually involved two or more players; some may refer to this as playing with a community of friends or family. Whereas the birth of digitisation that stems from old school arcade games such as SpaceWar in 1962 (Arpad, 2017), much more technologically advanced games today have often fall forefront of criticism that communities are reduced to individualism or isolation from physical, face-to-face community. A major player to the digitisation of games is the introduction of the Internet during the 1990s (Andrews, 2013), where it’s increased relevancy and functioning within video games provide a manicheistic belief, where one side of the argument suggests that with virtual spaces, we live in pseudo-communities (Katz, Rice, Acord, Dasgupta, & David, 2004, p.323). This conference paper aims to discuss that video games have not destroyed communities; rather they have provided an alternate planet. Online gaming does not diminish personalities or communities but rather, provide life skills, extend physical communities and utilise collective intelligence to solve issues quicker.

MMORPG Provides Life Skills

“Third Place”

The introduction of digitisation saw the migration from traditional board games to video games and the emergence of virtual worlds, also known as the ‘third place’. ‘Third places” in video games provide “a home away from home” and provided “feelings of being at ease” (Steinkuehler & Williams, 2006, p.890, Table 1, row 8). With physicality, individuals move from the presence of others whilst in the “games room”, to individual seating and playing in front of a digital screen. Media scholars in the 2000’s often evoked scepticism towards this shift from physical to virtual communities, regarding it as a distortion to societal engagement, often known as the “bowling alone” theory (Steinkuehler & Williams, 2006, p.885). However, the introduction of Massively Multiplayer Online Role-playing games (MMORPG) have given new meaning to gaming communities, offering as a alternate planet known as a “third place”, where individuals have the free will to enter and exit, unlike the real world bounded by various physical obligations (Steinkuehler & Williams, 2006, p.890-891). In these alternate spaces, players utilise it as a form of “informal sociability”, similar to the functions of local pubs or cafes (Steinkuehler & Williams, 2006, p.886). The “third place” is incredibly important to study in relation to our youths, as explored in the next paragraph.

From Timid Youths to Future Leaders

A definition of a community can be understood in four elements, “a place to live, a spatial unit, a way of life and a social system” (Sanders 1996, cited in Katz et al. 2004, p.317). According to a paper by Meredith, Hussain, & Griffiths (2009), teenagers in their late years often make up the major population of MMORPG players. As youths enter into these virtual worlds, their reputation or societal statuses do not matter (Steinkuehler & Williams, 2006), more importantly, they have the freedom to express themselves, in which they may not have the confidence to in real life (Frostling-Henningsson, 2009, p.558). Frostling-Henningsson (2009) supported this statement with a case study of a 15-year-old boy who is well-respected and lead groups of players in MMORPG. However, in real life, he has a poor relationship with his parents and low self-esteem due to weight-related issues. This example proves that friendships with strangers in online gaming communities can be a positive experience as the ‘third place’ offers a space unbounded by the unfavourable circumstances of real life, which in result hinders confidence growth. The success of the 15-year-old boy challenges the scepticism of the “bowling alone” theory, which suggested that with online spaces, there would be an increase in isolation. Instead, the boy developed self-confidence by nurturing other players, this is as Wellman & Gulia (1999, p.9) supports, “helping others can increase self-esteem, respect from others and status attainment”.

Rituals and Consequences

Much like real-world society and governments, virtual worlds also have policies and rules that keep players in check (Kovisto, 2003, p.1). In MMORPG, a guild is a community of players that help each other through utilising different abilities (Kovisto, 2003), as uniting for a common cause was of central importance (Frostling-Henningsson, 2009, p.559). Within guilds, players can also own houses that can serve both as a “personality” aspect and as a meeting place with other gamers (Kovisto, 2003, p.6). Guild houses in particular, are unique to this study as they provide a safe haven for members to store items that can be shared by others. Within this house, players can train together, hold meetings and also craft (Kovisto, 2003, p.6). Hierarchical ranking systems in guilds also provide structure for senior members to provide wisdom in terms of game knowledge, helping newer members and providing them with a sense of belonging (Kovisto, 2003, p.7). This reinforces communal values and encourages participatory culture, which as Jenkins (2010) supports; “members believe their contributions matter, feeling some degree of social connection with one another”. Guild houses in virtual worlds challenge traditional scholars such as Tonnies, as cited in Katz et al. (2004, p.322), who argued that with the arrival of technology, “natural basis of human life is swept away forever, alienating us from each other”. Simplicity and games can be said as a thing of the past as character complexity nowadays means games can offer high levels of character customisation. Besides appearance, external effects to a character have been increasingly realistic. In Ultima Online(UO), drinking (alcohol) holds realistic results on the character, as Kovisto (2003) describes with constant bloating and vomiting out of mana (magical energy). In open-world free-roaming games such as Grand Theft Auto(Vice City in particular), exercising has massive effects on players such as training more on exercise bikes to increase stamina, swimming for an increase in lung capacity or weights to have a bigger build. These are the rules and consequences of real life transferred and paralleled into virtual gaming world values. An absence of any of these activities can result in lower gaming experience because much like the real world, the consequences of not exercising can be as simple as not being able to run from point A to B, quicker than one would like.

Common Interest and Social Games can Extend Physical Communities

FIFA and GTA

Source: Sidemen, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-cE-1EDV2Xs

In Wellman and Gulia’s paper (1999, p.2), it explains that critics are often sceptical that the introduction of the Internet can be “meaningful or complete” and that it will lead people away from tangible face-to-face experiences. However, we should note that online games are generally controlled and played by humans and the feedback is occurring in real time (Klastrup, 2010, p.313). In common interest games such as FIFA, friends/football team members that play alongside each other in real-life teams can come together to do the same in a mode called ‘pro clubs’. Players would come online at the same time, meeting up “virtually”, playing in their usual football positions and working together via communicating through a party chat. This is an example of physical communities extending onto online communities, strengthening their ties. When individuals socialise more as Trepte, Reinecke, & Juechems, (2012) explains, familiarity with each other brings them closer in both offline and online environments, due to the growth and increase in similarities from conducting activities of interest.

Source: SpecAgentProduction, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cTD3j2_reHQ

In Grand Theft Auto (GTA), players can form new communities through forums based on common interests – one of the more popular ones, for example, is the car-meeting club. Within this virtual space, it becomes a “hallucination of the real”, where players can “make possible” (Frostling-Henningsson, 2009, p.557) by owning and modding expensive cars. Very often, this is unrealistic in life due to financial restraints; therefore GTA car clubs provide gamers “more experiences than real life could provide” (Frostling-Henningsson, 2009, p.557) through the formation of these virtual communities, which never existed before. In this community, players often make new friends, learn new things and participate in an experience that is unfeasible in real life.

Virtual Friends are Valuable

Social networking sites (SNS) have been another context where digital games have been integrated into people’s lives to maintain and create communities. Besides its popularity and relevancy over the past decade, Facebook has been utilising gaming companies to include social games. As these games require Internet connectivity, it creates and maintains relationships between friends and families (Baym, Zhang, Kunkel, Ledbetter, & Lin, 2007, p.737). During Christmas 2009, Farmville, a Facebook game with 83 million active monthly users (Di Loreto & Gouaich, 2010), introduced a seasonal campaign where players could receive gifts from their Facebook friends, in which cannot be bought (Di Loreto & Gouaich, 2010, p.7). This encouraged a “reciprocation behaviour” (Di Loreto & Gouaich, 2010, p.7) where players had to send gifts but also reach out to their ‘friend lists’ to request for these gifts, the hope there will be an exchange. For those regular players with strong ties and/or friends that were already playing the game, they might post on their feed to receive these gifts. As humans are “inherently social creatures”, with the “constant search of others to help share their interests and solve their problems” (Di Loreto & Gouaich, 2010, p.3), they have either strengthen existing ties in their ‘friend lists’ and/or created new friendships with strangers. Reaching out to strangers as an alternate solution to receive these gifts expands one’s communal circle as Hjorth (2011) supports that SNS sites maintain but also establishes new links.

There Is No Problem That Collective Intelligence Cannot Solve

ARG: Potentialities of a Bottom-Up Model

Traditionally in terms of politics and commercialisation, it is understood that a top-down process is instilled as higher authorities control what citizens receive. Likewise, with games, game developers often manufacture games that produce certain effects on consumers. Today, this has slowly diminished as game companies seek new ways to give consumers a say, encouraging their involvement with gameplay. This is Alternate Reality Games (ARG); it collates geographically dispersed groups of people together via making use of Web 2.0 tools such as messaging apps/SNS, wikis, and forums to name a few. Initially, from an online space then onto a physical location, they come together and utilise their skills to shape a story (Kim, Lee, Thomas, & Dombrowski, 2009). Generally, ARG differs from video games, as many participants are unaware of the gaming aspects especially with the absence of playing in front of a machine and the existence of fixed rules/specific pathways to take. In ARGs, stories are disseminated into jigsaw-like parts, which participants must collate and assemble (Kim et al., 2009). As citizens come together with their ‘jigsaw parts’, they become the storyteller themselves and not the game developers, hence the bottom-up model. Completing the game is through the gathering of strangers and the applicability of each of their pieces, a process of collective intelligence. Through this newly formed community of strangers, they are all valuable members because they each have something that can advance the gaming narrative.

According to Marx and Engels (as cited in Katz et al., 2004), a greater detachment of physical peer-to-peer presence will lose all hope of community in society. This article by Katz et al. written in 2004 was also during a period where Web 2.0 emerged. General consensus during the birth of Web 2.0 was often sceptical, but the introduction of ARG to utilise Web 2.0 tools has challenged that. A bottom-up model in participatory and collective intelligence takes advantage of Web 2.0 to “expand their social network to improve their chances of solving the next puzzle” (Kim et al., 2009). As gaming elements such as the will and motivation to complete it, ARG’s mentality in need for “stronger communities for the experience to be complete”, (Kim et al., 2009) pushes players to diversify personalities and skill sets in order to accomplish the storyline quickly. This is evident in the ARG titled ‘The Beast’, where developers curated 3 months worth of problems, only for collective intelligence and participatory behaviours of players to solve it within a day (Kim et al., 2009). With Web 2.0 tools, geographically dispersed players around the globe were able to work continuously and collectively, using various languages and specialities to come together, to accelerate solving the issue (Kim et al., 2009). As players reached out to different forms of players, they also created newer friendships and widened communities that would have been almost impossible to exist before Web 2.0 was introduced.

Conclusion and Discussions

In this conference paper, I have argued against traditional scholars and critics that the introduction of the Internet and more importantly its infiltration within gaming, have diminished interpersonal physical relationships and the values of community. Traditional studies often portray video games negatively, that youth’s isolation playing MMORPG can be quite detrimental. MMORPG games, however, provide a “third place” for youths to take a break from real world problems (Frostling-Henningsson, 2009), a “keyboard café” (Wellman & Gulia, 1999, p.18) in which real-life identity do not hinder one’s ability to lead a community of players. Secondly, a real-world footballing community of players can strengthen their communal ties by joining up on FIFA’spro clubs and stimulate the exact aspects of a real match, into the video game. Unachievable hobbies in real-life can also be achieved through games; GTA’s car meets allow car enthusiasts to dedicate spending in-game money on mods and meet up with other enthusiasts, forming new communities that never existed before. Reciprocal games on SNS sites also stimulate behaviours of giving, a system that encourages users to give as much as possible in an attempt to receive back. To achieve this, players often quest outside their social circle for help, extending their communities to give to strangers too. Unlike hardcore MMORPG or common interest and social games, ARG is different because users are applying problem-solving efforts without the utility of stereotypical gaming components. There is a constant scepticism at the success of digital games in creating new communities through isolating an individual and the confinements in front of a digital screen. However, ARG with the utilisation of technological tools and fundamentals of gaming narrative presents a different outlook to community formation as participants are forced to move from an online space to a physical mass. Regardless, all 3 contexts have proven to utilise gaming elements to form communities of real people.

There should be a push for future titles to encourage youths to take on leadership roles, which could have positive repercussions such as being leaders in the real world, transferring their skills of commanding teammates in party chats to real life command of co-workers.

Finally, an emphasis for games with a bottom-up approach should be significant moving forward; bottom-up games prove that problems can be solved with inclusivity, collective intelligence and an encouragement for participatory behaviours. As games were rather one-way previously due to its rather confined rules and storylines, bottom-up may be the way forward if these aspects can be transferred onto real-world situations, solving real-world problems.

Agree/disagree? Let me know what you think down below.

References

Andrews, E. (2013). Who invented the Internet? Retrieved from: https://www.history.com/news/who-invented-the-internet

Árpád, P. (2017). Technological Periods and Medial Paradigms of Computer Games. Journal of Media Research, 10(2), 52-67. DOI: 10.24193/jmr.28.4

Baym, N., Zhang. Y., Kunkel, A., Ledbetter, A., & Lin, M. (2007). Relational Quality and Media Use in Interpersonal Relationships. New Media & Society, 9(5). DOI: 10.1177/1461444807080339

Di Loreto, I., & Gouaich, A. (2010). Social Casual Games success is not so Casual. Research Report #RR – 10017 LIRMM, Universtiy of Montpellier – CNRS. Retrieved from: https://hal-lirmm.ccsd.cnrs.fr/file/index/docid/486934/filename/FunAndGames2010-03-22.pdf

Frostling-Henningsson, M. (2009). First-Person Shooter Games as a Way of Connecting to people: “Brothers in Blood”. CyberPsychology & Behaviour, 12(5), 557-562. DOI: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0345

Hjorth, L. (2011). Games and Gaming: An Introduction to New Media:Web 2.0, Social Media and Online Games. Retrieved from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/curtin/reader.action?docID=635418#

Jenkins, H. (2010). Why Participatory Culture Is Not Web 2.0: Some Basic Distinctions. Confessions of an Aca/Fan. Retrieved from: http://henryjenkins.org/2010/05/why_participatory_culture_is_n.html

Katz, J., Rice, R., Acord, S., Dasgupta, K., & David, K. (2004). Personal Mediated Communication and the Concept of Community in Theory and Practice. In P. Kalbfleisch (Ed.), Communication and Community: Communication Yearbook 28. Retrieved from: http://rrice.faculty.comm.ucsb.edu/A80KatzRiceAcordDasguptaDavid2004.pdf

Kim, J., Lee, E., Thomas, T., & Dombrowski, C. (2009). Storytelling in new media: The case of alternate reality games, 2001-2009. First Monday, 4(6). Retrieved from: https://www.firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2484/2199

Klastrup, L. (2010). International handbook of internet research: Understanding Online (Game)worlds. Retrieved from: https://link.library.curtin.edu.au/ereserve/DC60267025/0?display=1

Kovisto, E. (2003). Supporting Communities in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games by Game Design. Paper presented at the Digital Games Research Association Conference. Retrieved from: http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/05150.48442.pdf

Meredith, A., Hussain, Z., & Griffiths, M. (2009). Online gaming: a scooping study of massively multi-player online role playing games. Electronic Commerce Research, 9(1-2), 3-26. DOI: 10.1007/s10660-009-9029-1

Steinkuehler, C., & Williams, D. (2006). Where Everybody Knows Your (Screen) Name: Online Games as “Third Places”. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 11(4), 885-909. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00300.x

Trepte, S., Reinecke, L., & Juechems, K. (2012). The social side of gaming: How playing online computer games creates online and offline social support. Computers in Human Behaviour, 28. 832-839. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.003

Wellman, B., & Gulia, M. (1999). Net Surfers Don’t Ride Alone: Virtual Communities as Communities. In P. Kollock, & M. Smith (Eds.), Communities and Cyberspace. Retrieved from: http://groups.chass.utoronto.ca/netlab/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Net-Surfers-Dont-Ride-Alone-Virtual-Community-as-Community.pdf

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Firstly, can I just say how much I love the title for this paper, you’ve definitely hooked me as a reader there. Looking at those who still think that video games, means isolation, is such a prevalent thing even today when the entire society that is involved with games knows that this is not the case, so the discussion of this is very necessary, especially when you go through the motions of how games were originally brought about (Scrabble, Monopoly) to the way that games are today, MMORPGs.

The concepts about how games can really bring a person out of the shell, due to the fact that all reputations in real life are non-existent in the games online, brings up a lot of further discussions. Since your paper does argue that video games do not isolate people, do you think that as this further progresses and more is written and discussed about this fact, that these games might further be used within trying to help those with mental illnesses such as anxiety or depression due to the online social communication skills that can be found online? I know that your paper also discusses how the social aspects can be taken offline in physical aspects, but do you think the same could be applied with something such as anxiety or mental illness in the future?

Thank you,

Tiffany Kennedy,

18805992.

Hi Tiffany, I’m looking forward to hearing Christopher’s thoughts on your comments.

I’d just like to add that already we see video games acting to connect people with others, help them learn and provide a secure-feeling space for people that otherwise might really struggle, such as people on the Autism spectrum.

Here’s the links to a few articles found via Google scholar (just to show there’s loads of info freely accessible) if anyone is interested in learning more:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563215003581

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563216300188

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07317107.2013.846648

Cheers,

Ces

Hi Ces,

Thank you for adding this! Those are some really interesting articles. I am already aware of discussions on how gaming can help those on the Autism spectrum which is amazing, and I’d love to delve more into looking at that so thank you for sending that through!

Cheers,

Tiffany

Hi Tiffany,

Thank you for taking the time to read my paper and producing the comments.

You raise a really good question for the future study of this argument. Personally I feel that games can be a part of the solution, but never the actual real solution. Much like the 15-year-old example, MMORPG has helped him gained confidence within-in game, which would have lifted his public speaking abilities a little, but it doesn’t change his external circumstances in real life, once he switches off that console and removes that headphone, stepping into the real world with his problems thrown back at his face. But because of leadership in MMORPG, he might be able to grow in confidence a little by little as he ages, thanks to public speaking in MMORPG for example.

So in a sense, games is a kickstarter to solving real world issues, but it requires physical support and physical intervention to fully solve the issue. Games offer as help through that transition/process, but never the end point. For example, with the rise of Augmented Reality (AR), there was a recent example in Brazil where AR has helped kids through the process of vaccination and the fear of needle. Games has not physically helped them ‘get jabbed’ but it has helped them understand the process especially as an educational aspect and experience it without the trauma of physically seeing the needle. Here’s the link which better explains it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9CPVOt7QjcM

Hi Christopher!

Thank you for your reply. I definitely see where you’re coming from in your reply here, looking at games as a Kickstarter to certain issues when it comes to understanding, which I completely agree with. Thank you for also sending through that link which is really interesting!

I suppose with certain kids, only time will tell with whether certain games have a positive effect on their mental well being on slight confidence building as it is dependant on each person. There’s also the counter argument (which is barely an argument) where “politicians” such as “Trump” try to point blame to games for negative behaviours and well being, such as isolation which you do talk about, and your suggestion that gaming doesn’t change external circumstances in real life, i.e. problems that are already there, suggests that games do not have THAT much of an impact as some think there is (which is a positive thing in that circumstance). Thinking about your suggestions has brought this to mind, as looking through all this I do believe it depends on what type of gaming we are looking at (like augmented reality, as you suggest) or as Ces suggested kids that are on the Autism spectrum who use it to help them, compared to kids finding an escape for a few moments. Gaming is such a wide topic, there are so many factors to this. Thank you for your reply!

Cheers,

Tiffany.

Hi Christopher, your paper was a good read. Well done. I especially like the way you have thought outside the box by presenting videos and images within your conference paper.

If I can just play devil’s advocate for a minute – You write about a 15-year-old boy who, even though he is a leader amongst his fellow gamers has low self-esteem, weight issues, and poor familial relationships. Would he, had he not been lost in his “third place”, be experiencing a richer offline life?

Is there a place for balance or can we only find success in one life – online or off?

I agree that having a “third place” can be really beneficial for people who want an escape from various aspects of their life or to experience life inside a game where the character is of their own making. Speaking of “characters of their own making” – head over to my paper and read about the identity deception that is rife on LinkedIn profiles and why recruiters shouldn’t believe everything they find there….

Kind Regards,

Ces

https://networkconference.netstudies.org/2019Curtin/2019/04/30/linkedin-for-recruitment-no-thanks/

Hello Ces,

Thank you, that means a lot!

I also appreciate your effort in sourcing those scholarly articles, I’ll be sure to read them when I have a break or two during the week.

I completely agree with you about experiencing a richer offline life, this is the counter argument to my paper, this argument would make up the “two sides of the story” balance. As per my response to @Tiffany, I believe that games should never be an end point, games act as a guide, a narrative that ‘screams’ all things real life should be like. With or without games, those external circumstances in real life already existed for that 15-year-old boy, so the real question should be: “does games therefore, help him improve or is he just using it to experience a rich ONLINE life?”

Good point Christopher, in the case of this young man, and millions of people like him, games – especially ones where you find yourself immersed in a third place – may sometimes be the only place you feel safe and happy at times. They can be considered a blessing when we think of games like this.

Hi Christopher,

I really enjoyed your paper. You discussed some interesting points like people achieving the unachievable and growing in confidence through video games. You used some great articles to support this argument and your title, headings and pictures are eye-catching.

Why do you think scholars still refer to online games as isolating?

Do you think online and offline communities can be used for good in unison?

Hi AHanley.

Thanks for your reply!

I believe that with the rapid pace and growth of digitisation in games and the continual advancement and possibilities within new games have definitely brought many scholars and sceptics into a world of hysteria, that is, an instinct to fear things that alter ‘normal’ societal functioning, things that may be good for society but requires changes. To answer your question (which I think would cover both question) and as highlighted in many papers within this stream, there are two factors. Firstly, there are individuals that are fully invested in games and often have positive experiences in which they cannot experience from in the real-world, when explained to a ‘normal’ person, these experiences (or skills acquired in games) are not qualifiable. For e.g. in game leadership and confidence is not valid if it’s not replicated in the real-world. I do argue though, that scholars shouldn’t understand this at base level, that it’s not replicated, but to understand that it’s a starting point for individuals to gain confidence and then transferring these skills into real life. Secondly, no matter how entwined online and offline communities are, one must understand that each is to their own, hence the “third place’ easily entered and exited. When one understands this, then it’s possible to see how skills acquired in online gaming can be transferrable to real-world situations and not depended on it. I argue that each is to their own because one should not rely on either or to thrive.

I hope this makes sense!

Hi Christopher,

It was very interesting to read this paper and I very much liked your point about MMORPGs being a ‘third space’ where someone who might otherwise have a difficult or unsatisfactory life being able to flourish in the online gaming world.

Do you think these sorts of leadership/teamwork skills are going to be scouted and sought out by eSports teams or even professionals in other educational fields in the future? I could definitely see it happening with the way eSports is growing and these type of leadership and teamwork skills can apply to other things for sure.

It was also interesting reading about SNS and their ability to connect people. I think a weird benefit of this type of interaction is that it’s very non-intrusive and is a very lighthearted way of connecting with people, what do you think?

Thanks for the great read,

Louis

Hi Louis,

Thanks for taking the time with reading my paper and providing feedback.

You have raised a really good point about E-Sports and I especially love the term you used with “scouting”. Personally, I believe that E-Sports is seriously underrated, that many people believe it’s ridiculous that gamers get paid sitting on a chair, playing games. Often these same people don’t realise that not everyone makes it onto the big stage (E-Sport teams and eventually major tournaments), that often gaming goes from a recreation into a serious activity, consisting of hours of grinding referred to as “training”, to climb and be qualified for E-Sport tournaments with real large monetary prizes. E-Sports is slowly becoming normalise and prevalent within different contexts of society. With proper and professional soccer teams, there are now also E-Sport teams that represent them such as Perth Glory for example! https://www.perthglory.com.au/news/e-league-duo-raring-go

In terms of different contexts, there are world cups, massive arenas with spectators that attend to watch “a bunch of gamers play video games against each other” and more recently, the ability to punt/place bets on various E-Sport matches. My apologies if I went off on a tangent, but to answer your question and in relation to my paper’s example of the 15-year-old, I say yes that these in-game skills are valuable. What may be perceived as “false confidence or false skills” that is only present when gaming, can be appreciated if a player is good enough to make it to the major stage of E-Sports. I don’t think it’s a bad thing at all, if this 15-year-old boy goes onto the big stage, making honest and good money doing what he does best – playing video games. Which headline would read better? “15-year-old boy with no confidence, isolated in his room in the corner” vs. “15-year-old boy, the youngest ever E-Sport champion”?

To answer your second question, I will agree once again. I think games on SNS became a success because it was able to keep consistent the values of SNS, yet incorporate gaming elements in a lighthearted way. With SNS, it has the ability to connect to people yet do so in a non-intrusive way, game invites are the same that invitees have the ability to ignore these invites or even block them, yet it still stretches out a virtual hand, inviting them to play this game, if they wish to.

Thanks for your insight once again!

Hi Christopher,

First off I’d like to say how much I appreciate that you have a meme title, excellent work I wish more people had opted for this. I found your paper very interesting and very well written. I am not overly familiar with ARG, how are these types of games usually played, mobile app? It reminds me of a TED talk I saw, I’ll link it here, where the speaker was describing inventing a game called World Without Oil, it was a kind of immersive experience where you had to problem solve and figure out how you would live your life if there was a shortage of petrol. They invented other similar ones to get people to come together to problem solve around environmental issues. Could these be considered ARG’s?

https://www.ted.com/talks/jane_mcgonigal_gaming_can_make_a_better_world?language=en

Hi CSligh,

Thank you for your kind words and also spotting my meme title! Was seriously worried that many people won’t get it.

ARG’s are story narrative parts distributed by the gaming company to participants (I’m guessing you have to opt-in or subscribe to be part of it) through Web 2.0 methods such as email, SNS, wikis, forums to name a few, within these are clues to the game. Participants are somewhat made known to each other and each of them consist of a unique clue (jig-saw), which they utilise Web 2.0 tools to communicate and eventually come together. They can usually solve the problem quicker than expected because they all have unique characteristic and skill sets that accelerate solving this issue then if let’s say, by one person.

Yes good find! World Without Oil is definitely a great example of an ARG because it is a bottom up model, where game developers set the narrative but tasks participants to solve the problem utilising Web 2.0 tools. I believe games like this have transformed the meaning and stereotypes that all games are “hardcore” and “isolating” and your example perfectly explains my paper, that there are 3 different kind of contexts within gaming communities. ARG is definitely very unique and different from games made to help confidence growth or games that is a space to be social (as my first 2 contexts explores), ARG is incredibly important to our future because gaming elements are embedded into our real-world issues, and if it becomes more normalised and prevalent, just imagine how many problems we can solve in this world?

Thanks for your contribution once again, good sharing to the others with the TED talk link too!

Hi Christopher,

You hooked me with the title, I understood the reference.

I loved the usage of media to reinforce your argument.

I agree with your sentiment that online games have enabled people to seek out others with common interests and facilitate the interaction between said people.

GTA Online is one such example of a game that has gained such a following that the users have taken the sandbox they were handed and made it into their own place to gather and spend time with people.

Where else can someone with hardly any real world money get together with their friends on a yacht and sip on some digital champagne?

Hi EHanton,

I appreciate that you were able to identify and connect with the title and the graphics! You do sound like you play GTA too and I am glad that it makes the two of us that are able to relate to these examples. Yes, you are very right, the game began as an open-world and car clubs would not have been something intended by Rockstar or would have been imagined by anyone during the initial introduction of this game. It is through people’s interests, innovation and creativity to create this opportunity, moulding what seemed like a confined and rigid world (with rules) to form groups like these. Even though there are a limited number of cars and as many modifications as one can do (and very often many share similar model cars but in variation of aesthetics), players are still able to seek enjoyment and pleasure, but more importantly they have “made it their own place to gather and spend time with people”. Pre-existing communities within the game have now been expanded or rather, refined, to specific communities of self-interest. I love your reference with the yacht and champagne sipping about GTA, I think that is going to be stuck in my head (visually) for the next few days now each time I think about GTA!

Thanks once again!

Hi Chris,

Loved the the title of this conference paper. Very relatable when talking about video games and has definitely made me continue to read the article. The argument formed here is well thought out and the range of sources used within each segment of your paper is great as I struggled to balance my sources throughout my paper. I particularly liked the case study on the 15 year old which adds further depth to that section of the article.

I only have one criticism of the article but it is not too major in terms of swaying the article away from the intended argument. In the section ‘Rituals and Consequences’ you mentioned that Grand Theft Auto Vice City allows the player to train their characters physical skills which will affect how the in-game character plays. I believe you are mentioning Grand Theft Auto San Andreas which allows the player to train the in-game characters physical stats and is widely regarded as one of the best GTA games of the current generation of consoles at the time. GTA Vice City however did not contain a way to train the physical stats of the in-game character because it re-used a majority of the game assets from GTA 3 which did not allow the character to swim or go to gyms due to the constraints that the company had with the game at the time.

Hi MHanafi,

I am very glad and relieved to hear that you continued reading past the title! Thank you for your kind feedback on my paper, I appreciate that you value my paper being balanced but I think it is good to have a one-sided argument too, there is no right or wrong as cliche as it sounds. With games especially, there has been many good experiences and upshots from it, but there will also be many negative repercussions and consequences as games becomes more complex. As long as you have stated your argument, proved and maintain consistent to it, just continue believing in what you are writing!

Yes indeed you are right, a very good spot! Thank you for identifying that it is San Andreas, I always had difficulties trying to distinct both of those games as I heavily played both of them when I was younger. To think about it now, I do truly recall it being San Andreas whenever I ride that bike on one of the alleys on Grove Street (true nostalgia here), I earned some sort of stamina increase. I have to add as well, the recent memes of “Ah, here we go again” has helped me remember it too! Just a fun fact I guess.

Hi Cristopher

The title of your paper itself is really catchy and is in line with online pop culture as well. Your paper is indeed a counter argument against my own paper and I found yours to be quite an insightful perspective on the subject. We often tend to neglect the friendships that are formed online and how gamers are able to make friends on communities that were not originally designed for friendship but rather as an enhancement to classic solo gameplay. Nonetheless, does the online environment really provide a space for those who are considered as isolating themselves from society or is it actually a space where the weak gets preyed upon. I believe we have discussed this in the comment thread on my conference paper.

Thanks for having guided me to your paper.